Production Possibilities and Comparative Advantage, Revisited

To produce phones, any country must use resources—

In some cases, it’s easy to see why the opportunity cost of producing a good is especially low in a given country. Consider, for example, shrimp—

Conversely, other goods are not produced as easily in Vietnam as in the United States. For example, Vietnam doesn’t have the base of skilled workers and technological know-

In other cases, matters are a bit less obvious. It’s as easy to assemble smartphones in the United States as it is in China, and Chinese electronics workers are, if anything, less efficient than their U.S. counterparts. But Chinese workers are a lot less productive than U.S. workers in other areas, such as automobile and chemical production. This means that diverting a Chinese worker into assembling phones reduces output of other goods less than diverting a U.S. worker into assembling phones. That is, the opportunity cost of assembling phones in China is less than it is in the United States.

Notice that we said the opportunity cost of assembling phones. As we’ve seen, most of the value of a “Chinese made” phone actually comes from other countries. For the sake of exposition, however, let’s ignore that complication and consider a hypothetical case in which China makes phones from scratch.

So we say that China has a comparative advantage in producing smartphones. Let’s repeat the definition of comparative advantage from Chapter 2: A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if the opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower for that country than for other countries.

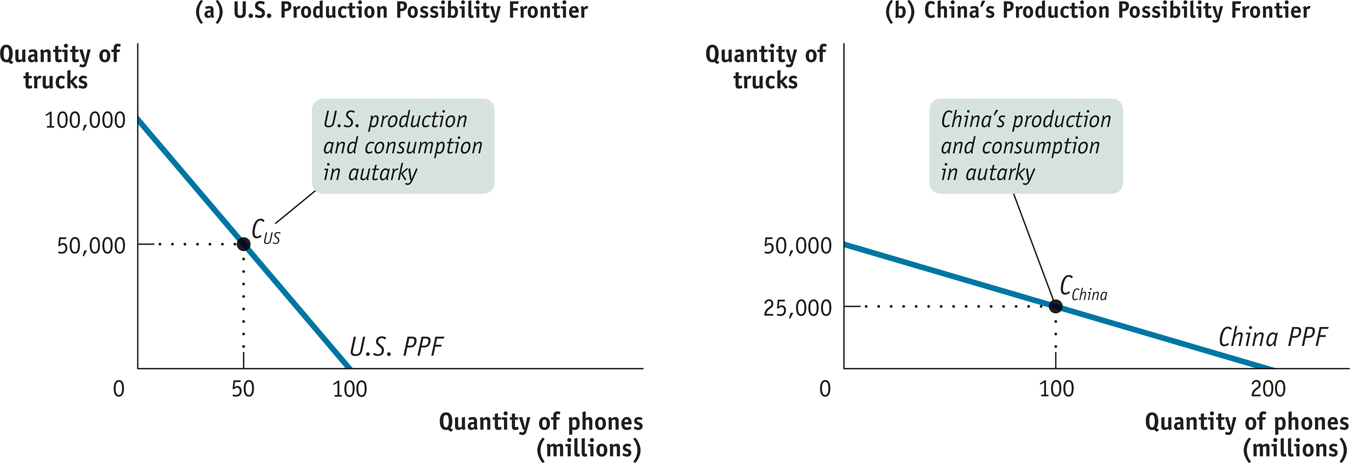

Figure 5-2 provides a hypothetical numerical example of comparative advantage in international trade. We assume that only two goods are produced and consumed, phones and Ford trucks, and that there are only two countries in the world, the United States and China. The figure shows hypothetical production possibility frontiers for the United States and China.

The Ricardian model of international trade analyzes international trade under the assumption that opportunity costs are constant.

As in Chapter 2, we simplify the model by assuming that the production possibility frontiers are straight lines, as shown in Figure 2-1, rather than the more realistic bowed-

In Figure 5-2 we show a situation in which the United States can produce 100,000 trucks if it produces no phones, or 100 million phones if it produces no trucks. Thus, the slope of the U.S. production possibility frontier, or PPF, is −100,000/100 = −1,000. That is, to produce an additional million phones, the United States must forgo the production of 1,000 trucks.

Similarly, China can produce 50,000 trucks if it produces no phones or 200 million phones if it produces no trucks. Thus, the slope of China’s PPF is −50,000/200 = −250. That is, to produce an additional million phones, China must forgo the production of 250 trucks.

Autarky is a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries.

Economists use the term autarky to refer to a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries. We assume that in autarky the United States chooses to produce and consume 50 million phones and 50,000 trucks. We also assume that in autarky China produces 100 million phones and 25,000 trucks.

The trade-

|

|

U.S. Opportunity Cost |

|

Chinese Opportunity Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 million phones |

1,000 trucks |

> |

250 trucks |

|

1 truck |

1,000 phones |

< |

4,000 phones |

TABLE 5-

As we learned in Chapter 2, each country can do better by engaging in trade than it could by not trading. A country can accomplish this by specializing in the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage and exporting that good, while importing the good in which it has a comparative disadvantage.

Let’s see how this works.