The Nature of Macroeconomics

What makes macroeconomics different from microeconomics? The distinguishing feature of macroeconomics is that it focuses on the behavior of the economy as a whole.

Macroeconomic Questions

Table 6-1 lists some typical questions that involve economics. A microeconomic version of the question appears on the left paired with a similar macroeconomic question on the right. By comparing the questions, you can begin to get a sense of the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

|

Microeconomic Questions |

Macroeconomic Questions |

|---|---|

|

Should I go to business school or take a job right now? |

How many people are employed in the economy as a whole this year? |

|

What determines the salary offered by Citibank to Cherie Camajo, a new MBA? |

What determines the overall salary levels paid to workers in a given year? |

|

What determines the cost to a university or college of offering a new course? |

What determines the overall level of prices in the economy as a whole? |

|

What government policies should be adopted to make it easier for low- |

What government policies should be adopted to promote employment and growth in the economy as a whole? |

|

What determines whether Citibank opens a new office in Shanghai? |

What determines the overall trade in goods, services, and financial assets between the United States and the rest of the world? |

TABLE 6-

As these questions illustrate, microeconomics focuses on how decisions are made by individuals and firms and the consequences of those decisions. For example, we use microeconomics to determine how much it would cost a university or college to offer a new course, which includes the instructor’s salary, the cost of class materials, and so on. The school can then decide whether or not to offer the course by weighing the costs and benefits.

Macroeconomics, in contrast, examines the overall behavior of the economy—

You might imagine that macroeconomic questions can be answered simply by adding up microeconomic answers. For example, the model of supply and demand we introduced in Chapter 3 tells us how the equilibrium price of an individual good or service is determined in a competitive market. So you might think that applying supply and demand analysis to every good and service in the economy, then summing the results, is the way to understand the overall level of prices in the economy as a whole.

But that turns out not to be right: although basic concepts such as supply and demand are as essential to macroeconomics as they are to microeconomics, answering macroeconomic questions requires an additional set of tools and an expanded frame of reference.

Macroeconomics: The Whole Is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

If you occasionally drive on a highway, you probably know what a rubber-

What makes it so annoying is that the length of the traffic jam is greatly out of proportion to the minor event that precipitated it. Because some drivers hit their brakes in order to rubber-

Understanding a rubber-

Consider, for example, what macroeconomists call the paradox of thrift: when families and businesses are worried about the possibility of economic hard times, they prepare by cutting their spending. This reduction in spending depresses the economy as consumers spend less and businesses react by laying off workers. As a result, families and businesses may end up worse off than if they hadn’t tried to act responsibly by cutting their spending.

This is a paradox because seemingly virtuous behavior—

Or consider what happens when something causes the quantity of cash circulating through the economy to rise. An individual with more cash on hand is richer. But if everyone has more cash, the long-

A key insight of macroeconomics, then, is that the combined effect of individual decisions can have results that are very different from what any one individual intended, results that are sometimes perverse. The behavior of the macroeconomy is, indeed, greater than the sum of individual actions and market outcomes.

Macroeconomics: Theory and Policy

In a self-

According to Keynesian economics, economic slumps are caused by inadequate spending, and they can be mitigated by government intervention.

Monetary policy uses changes in the quantity of money to alter interest rates and affect overall spending.

Fiscal policy uses changes in government spending and taxes to affect overall spending.

To a much greater extent than microeconomists, macroeconomists are concerned with questions about policy, about what the government can do to make macroeconomic performance better. This policy focus was strongly shaped by history, in particular by the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Before the 1930s, economists tended to regard the economy as self-

The Great Depression changed all that. The sheer scale of the catastrophe, which left a quarter of the U.S. workforce without jobs and threatened the political stability of many countries—

In 1936 the British economist John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “canes”) published The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, a book that transformed macroeconomics. According to Keynesian economics, a depressed economy is the result of inadequate spending. In addition, Keynes argued that government intervention can help a depressed economy through monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy uses changes in the quantity of money to alter interest rates, which in turn affect the level of overall spending. Fiscal policy uses changes in taxes and government spending to affect overall spending.

In general, Keynes established the idea that managing the economy is a government responsibility. Keynesian ideas continue to have a strong influence on both economic theory and public policy: in 2008 and 2009, Congress, the White House, and the Federal Reserve (a quasi-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Fending Off Depression

Fending Off Depression

In 2008 the world economy experienced a severe financial crisis that was all too reminiscent of the early days of the Great Depression. Major banks teetered on the edge of collapse; world trade slumped. In the spring of 2009, the economic historians Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke, reviewing the available data, pointed out that “globally we are tracking or even doing worse than the Great Depression.”

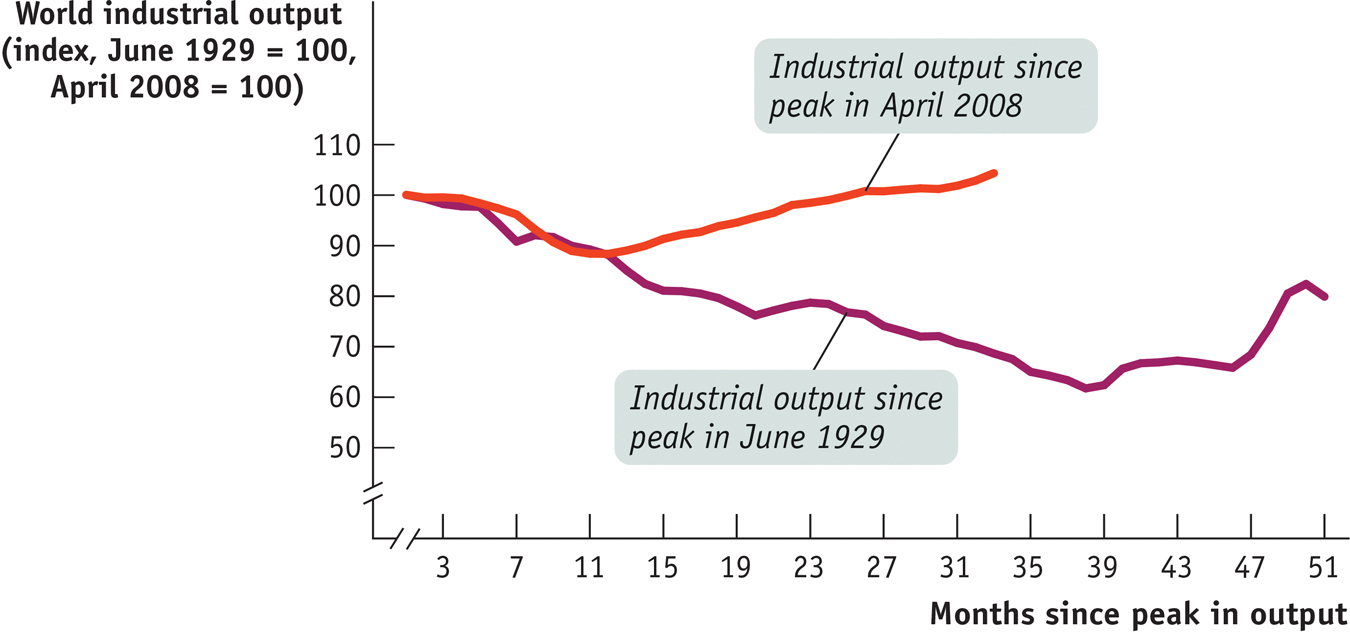

But the worst did not, in the end, come to pass. Figure 6-1 shows one of Eichengreen and O’Rourke’s measures of economic activity, world industrial production, during the Great Depression (the top line) and during the Great Recession (the bottom line). During the first year the two crises were indeed comparable. But fortunately, one year into the Great Recession, world production leveled off and turned around. In contrast, three years into the Great Depression world production continued to fall. Why the difference?

At least part of the answer is that policy makers responded very differently. During the Great Depression, it was widely argued that the slump should simply be allowed to run its course. Any attempt to mitigate the ongoing catastrophe, declared Joseph Schumpeter—

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, by contrast, interest rates were slashed, and a number of countries, the United States included, used temporary increases in spending and reductions in taxes in an attempt to sustain spending. Governments also moved to shore up their banks with loans, aid, and guarantees.

Many of these measures were controversial, to say the least. But most economists believe that by responding actively to the Great Recession—

Quick Review

Microeconomics focuses on decision making by individuals and firms and the consequences of the decisions made. Macroeconomics focuses on the overall behavior of the economy.

The combined effect of individual actions can have unintended consequences and lead to worse or better macroeconomic outcomes for everyone.

Before the 1930s, economists tended to regard the economy as self-

regulating. After the Great Depression, Keynesian economics provided the rationale for government intervention through monetary policy and fiscal policy to help a depressed economy.

6-1

Question 6.1

Which of the following questions involve microeconomics, and which involve macroeconomics? In each case, explain your answer.

Why did consumers switch to smaller cars in 2008?

Why did overall consumer spending slow down in 2008?

Why did the standard of living rise more rapidly in the first generation after World War II than in the second?

Why have starting salaries for students with geology degrees risen sharply of late?

What determines the choice between rail and road transportation?

Why did salmon get much cheaper between 1980 and 2000?

Why did inflation fall in the 1990s?

Question 6.2

In 2008, problems in the financial sector led to a drying up of credit around the country: home-

buyers were unable to get mortgages, students were unable to get student loans, car- buyers were unable to get car loans, and so on. Explain how the drying up of credit can lead to compounding effects throughout the economy and result in an economic slump.

If you believe the economy is self-

regulating, what would you advocate that policy makers do? If you believe in Keynesian economics, what would you advocate that policy makers do?

Solutions appear at back of book.