The Circular-Flow Diagram, Revisited and Expanded

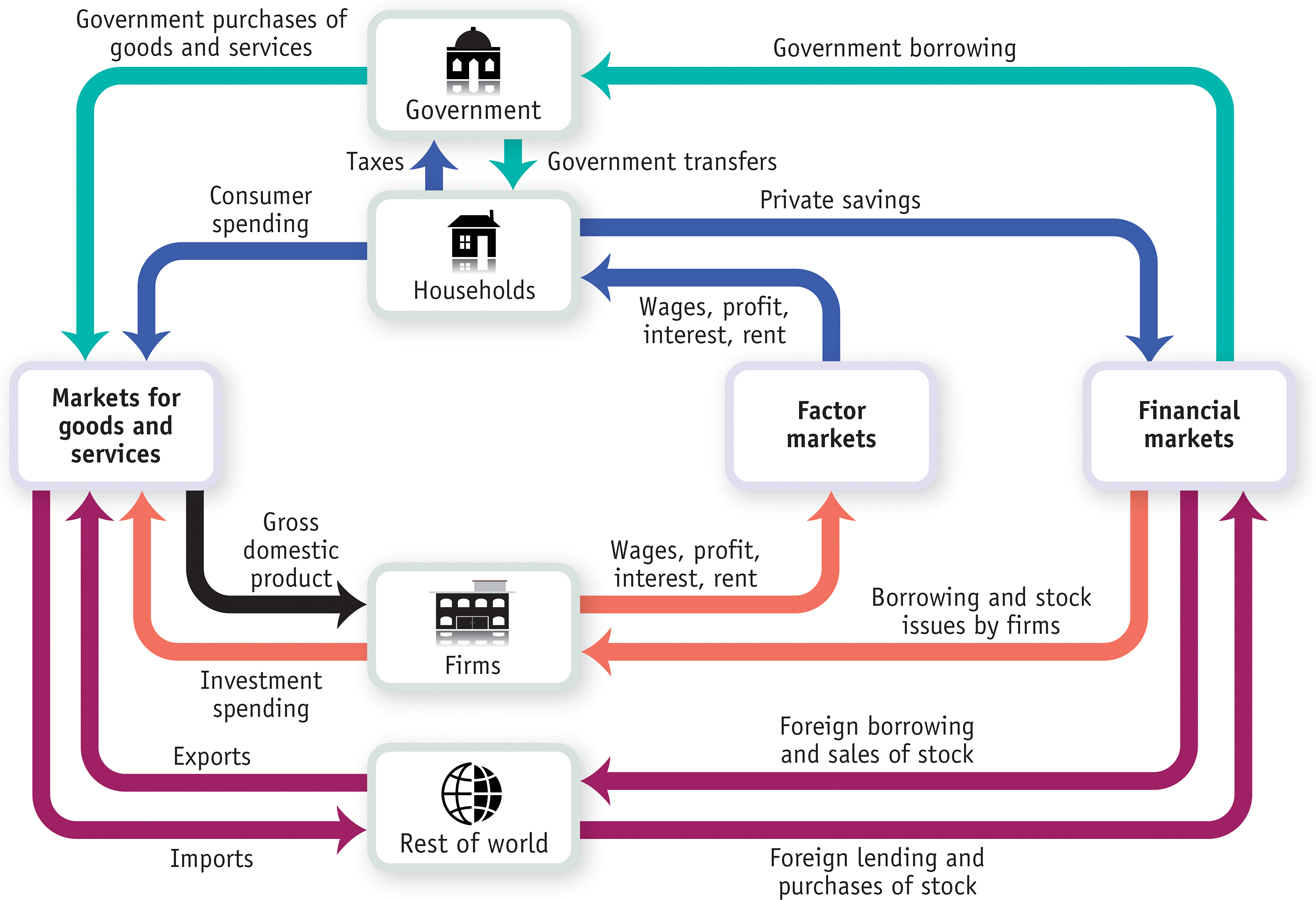

To understand the principles behind the national accounts, it helps to look at Figure 7-1, a revised and expanded circular-

Consumer spending is household spending on goods and services.

Figure 2-7 showed a simplified world containing only two kinds of “inhabitants,” households and firms. And it illustrated the circular flow of money between households and firms, which remains visible in Figure 7-1. In the markets for goods and services, households engage in consumer spending, buying goods and services from domestic firms and from firms in the rest of the world.

Households also own factors of production—

A stock is a share in the ownership of a company held by a shareholder.

But households derive additional income from their indirect ownership of the physical capital used by firms, mainly in the form of stocks, shares in the ownership of a company, and from direct ownership of bonds, borrowing by firms in the form of an IOU that pays interest. So the income households receive from the factor markets includes profits distributed to shareholders known as dividends, and the interest payments on bonds held by bondholders. Finally, households receive rent in return for allowing firms to use land or structures that they own. So households receive income in the form of wages, profit, interest payments, and rent via factor markets.

A bond is borrowing in the form of an IOU that pays interest.

In our original, simplified circular-

Government transfers are payments by the government to individuals for which no good or service is provided in return.

First, households don’t get to keep all the income they receive via the factor markets. They must pay part of their income to the government in the form of taxes, such as income taxes and sales taxes. In addition, some households receive government transfers—

Disposable income, equal to income plus government transfers minus taxes, is the total amount of household income available to spend on consumption and to save.

Private savings, equal to disposable income minus consumer spending, is disposable income that is not spent on consumption.

Second, households normally don’t spend all of their disposable income on goods and services. Instead, a portion of their income is typically set aside as private savings, which goes into financial markets where individuals, banks, and other institutions buy and sell stocks and bonds as well as make loans. As Figure 7-1 shows, the financial markets also receive funds from the rest of the world and provide funds to the government, to firms, and to the rest of the world.

The banking, stock, and bond markets, which channel private savings and foreign lending into investment spending, government borrowing, and foreign borrowing, are known as the financial markets.

Before going further, we can use the box representing households to illustrate an important general feature of the circular-

Government borrowing is the total amount of funds borrowed by federal, state, and local governments in the financial markets.

Now let’s look at the other types of inhabitants we’ve added to the circular-

Government purchases of goods and services are total expenditures on goods and services by federal, state, and local governments.

Goods and services sold to other countries are exports. Goods and services purchased from other countries are imports.

The rest of the world participates in the U.S. economy in three ways.

Some of the goods and services produced in the United States are sold to residents of other countries. For example, more than half of America’s annual wheat and cotton crops are sold abroad. Goods and services sold to other countries are known as exports. Export sales lead to a flow of funds from the rest of the world into the United States to pay for them.

Some of the goods and services purchased by residents of the United States are produced abroad. For example, many consumer goods are now made in China. Goods and services purchased from residents of other countries are known as imports. Import purchases lead to a flow of funds out of the United States to pay for them.

Foreigners can participate in U.S. financial markets by making transactions. Foreign lending—

lending by foreigners to borrowers in the United States, and purchases by foreigners of shares of stock in American companies— generates a flow of funds into the United States from the rest of the world. Conversely, foreign borrowing— borrowing by foreigners from U.S. lenders and purchases by Americans of stock in foreign companies— leads to a flow of funds out of the United States to the rest of the world.

Finally, let’s go back to the markets for goods and services. In Chapter 2 we focused only on purchases of goods and services by households. We now see that there are other types of spending on goods and services, including government purchases, investment spending by firms, imports, and exports.

Inventories are stocks of goods and raw materials held to facilitate business operations.

Notice that firms also buy goods and services in our expanded economy. For example, an automobile company that is building a new factory will buy investment goods—

Investment spending is spending on productive physical capital—

You might ask why changes to inventories are included in investment spending—

It’s also important to understand that investment spending includes spending on construction of any structure, regardless of whether it is an assembly plant or a new house. Why include construction of homes? Because, like a plant, a new house produces a future stream of output—

Suppose we add up consumer spending on goods and services, investment spending, government purchases of goods and services, and the value of exports, then subtract the value of imports. This gives us a measure of the overall market value of the goods and services the economy produces. That measure has a name: it’s a country’s gross domestic product. But before we can formally define gross domestic product, or GDP, we have to examine an important distinction between classes of goods and services: the difference between final goods and services versus intermediate goods and services.