Inflation Is Easy; Disinflation Is Hard

Disinflation is the process of bringing the inflation rate down.

There is not much evidence that a rise in the inflation rate from, say, 2% to 5% would do a great deal of harm to the economy. Still, policy makers generally move forcefully to bring inflation back down when it creeps above 2% or 3%. Why? Because experience shows that bringing the inflation rate down—

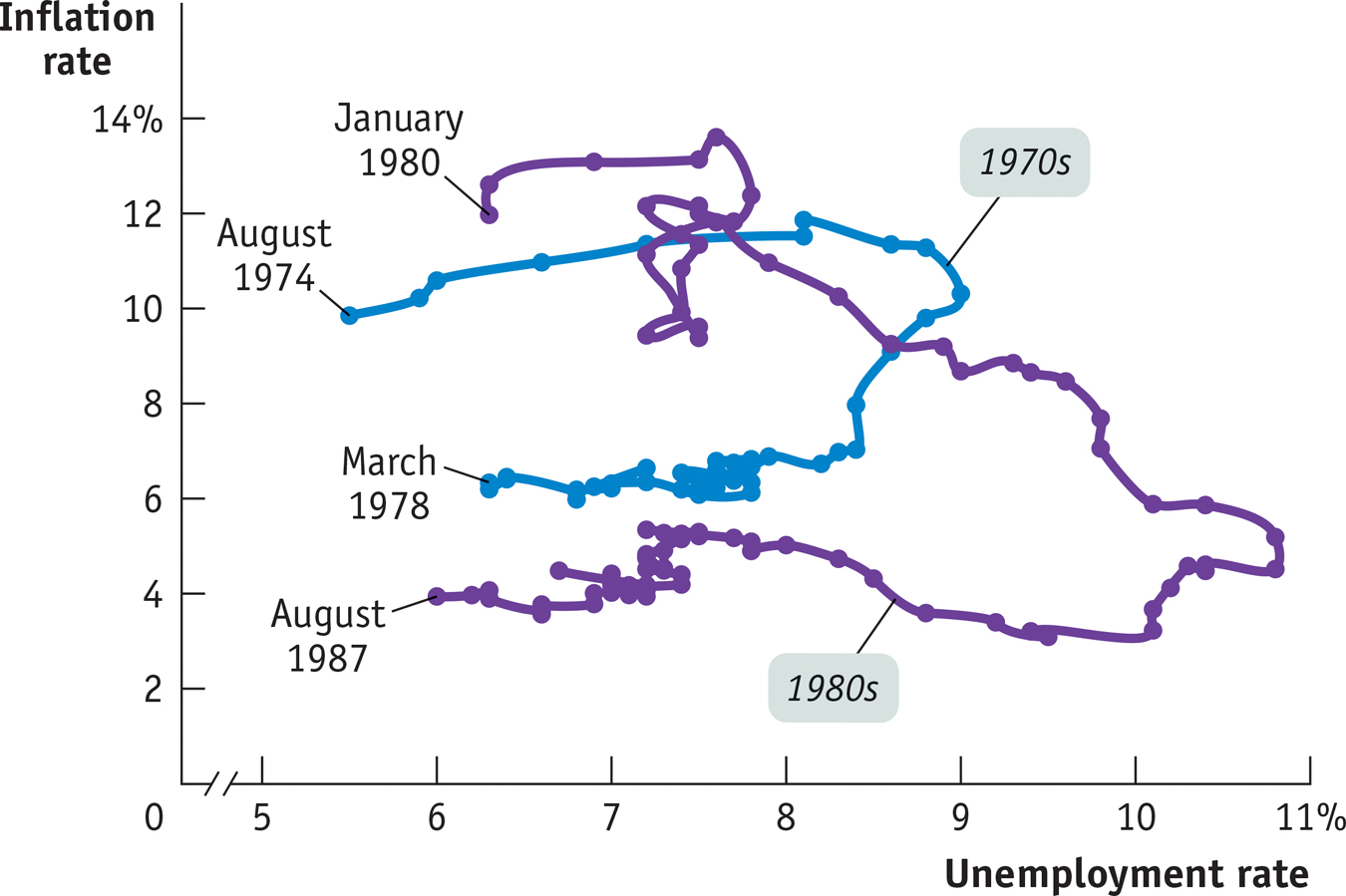

Figure 8-13 shows what happened during two major episodes of disinflation in the United States, in the mid-

According to many economists, these periods of high unemployment that temporarily depressed the economy were necessary to reduce inflation that had become deeply embedded in the economy. The best way to avoid having to put the economy through a wringer to reduce inflation, however, is to avoid having a serious inflation problem in the first place. So policy makers respond forcefully to signs that inflation may be accelerating as a form of preventive medicine for the economy.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Israel’s Experience With Inflation

Israel’s Experience With Inflation

It’s often hard to see the costs of inflation clearly because serious inflation problems are often associated with other problems that disrupt economic life, notably war or political instability (or both). In the mid-

As it happens, one of the authors spent a month visiting at Tel Aviv University at the height of the inflation, so we can give a first-

First, the shoe-

Second, although menu costs weren’t that visible to a visitor, what you could see were the efforts businesses made to minimize them. For example, restaurant menus often didn’t list prices. Instead, they listed numbers that you had to multiply by another number, written on a chalkboard and changed every day, to figure out the price of a dish.

Finally, it was hard to make decisions because prices changed so much and so often. It was a common experience to walk out of a store because prices were 25% higher than at one’s usual shopping destination, only to discover that prices had just been increased 25% there, too.

Quick Review

The real wage and real income are unaffected by the level of prices.

Inflation, like unemployment, is a major concern of policy makers—

so much so that in the past they have accepted high unemployment as the price of reducing inflation. While the overall level of prices is irrelevant, high rates of inflation impose real costs on the economy: shoe-

leather costs, menu costs, and unit- of- account costs. The interest rate is the return a lender receives for use of his or her funds for a year. The real interest rate is equal to the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. As a result, unexpectedly high inflation helps borrowers and hurts lenders. With high and uncertain inflation, people will often avoid long-

term investments. Disinflation is very costly, so policy makers try to avoid getting into situations of high inflation in the first place.

8-3

Question 8.7

The widespread use of technology has revolutionized the banking industry, making it much easier for customers to access and manage their assets. Does this mean that the shoe-

leather costs of inflation are higher or lower than they used to be? Question 8.8

Most people in the United States have grown accustomed to a modest inflation rate of around 2% to 3%. Who would gain and who would lose if inflation unexpectedly came to a complete stop over the next 15 or 20 years?

Solutions appear at back of book.

Day Labor in the Information Age

By the usual measures, California-

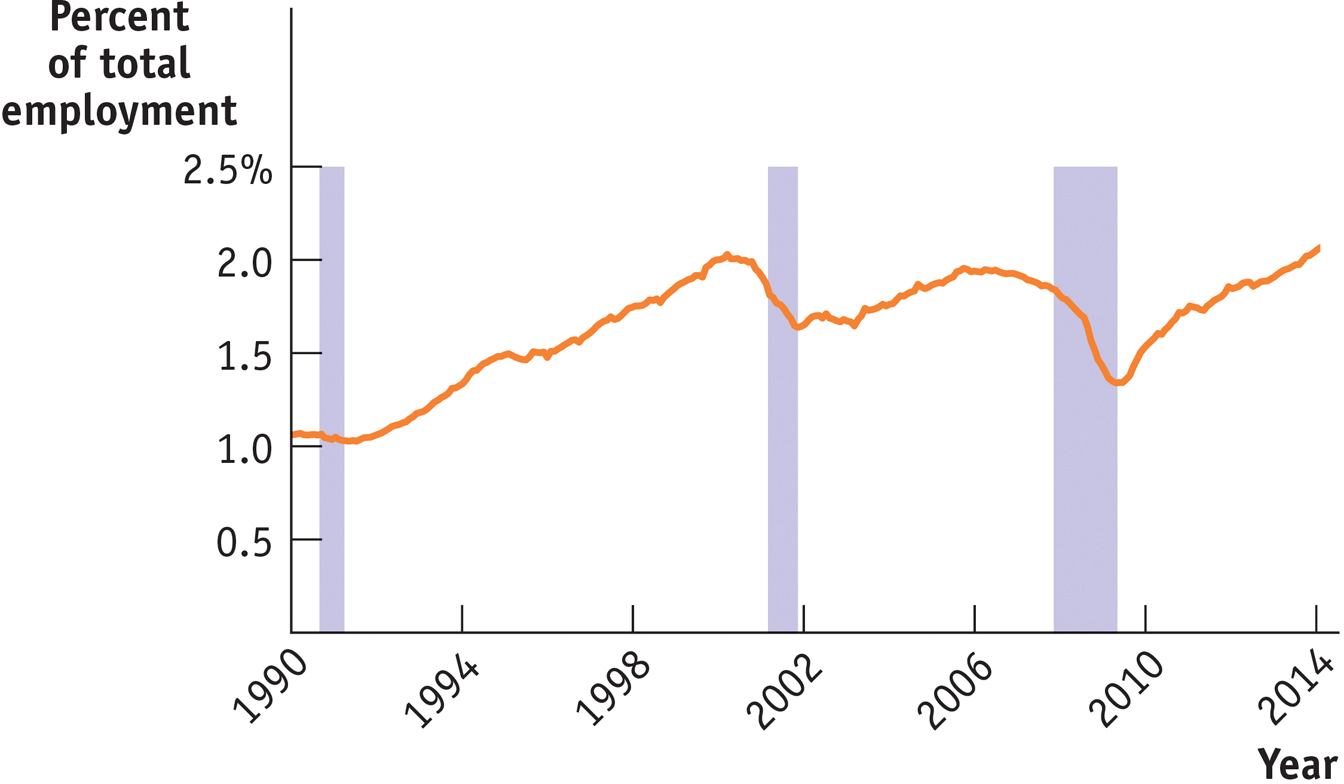

While most American workers consistently work for a single employer, temporary workers have always accounted for a significant portion of the labor force. On urban street corners across America, workers line up early each morning in the hope of getting day jobs in industries like construction where the need for workers fluctuates, sometimes unpredictably. For more skilled workers, there are temporary staffing agencies like Allegis Group that provide workers on a subcontracting basis, from a few days to months at a time. Figure 8-14 shows the share of temporary employment accounted for by these agencies in total employment. As you can see, in the late stages of the economic expansion in the 1990s and the 2000s, temporary employment soared as companies needed more workers but had difficulty hiring permanent employees in a tight labor market. Temporary employment then proceeded to plunge once demand for additional workers fell off.

At first glance, the rapid growth of temporary employment since the end of the 2007–

One answer may be the way in which advances in technology have opened up a new breed of services. Manual laborers might still be lining up on street corners, but information technology workers and other professionals were increasingly finding temporary, freelance work through web-

By 2014 Elance-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 8.9

Use the flows shown in Figure 8-7 to explain the role of temporary staffing in the economy.

Question 8.10

What is the likely effect of improved matching of job-

Question 8.11

What does the fact that temporary staffing fell sharply during the 2008–