Job Creation and Job Destruction

Even during good times, most Americans know someone who has lost his or her job. In July 2007, the U.S. unemployment rate was only 4.7%, relatively low by historical standards. Yet in that month there were 4.5 million “job separations”—terminations of employment that occur because a worker is either fired or quits voluntarily.

There are many reasons for such job loss. One is structural change in the economy: industries rise and fall as new technologies emerge and consumers’ tastes change. For example, employment in high-

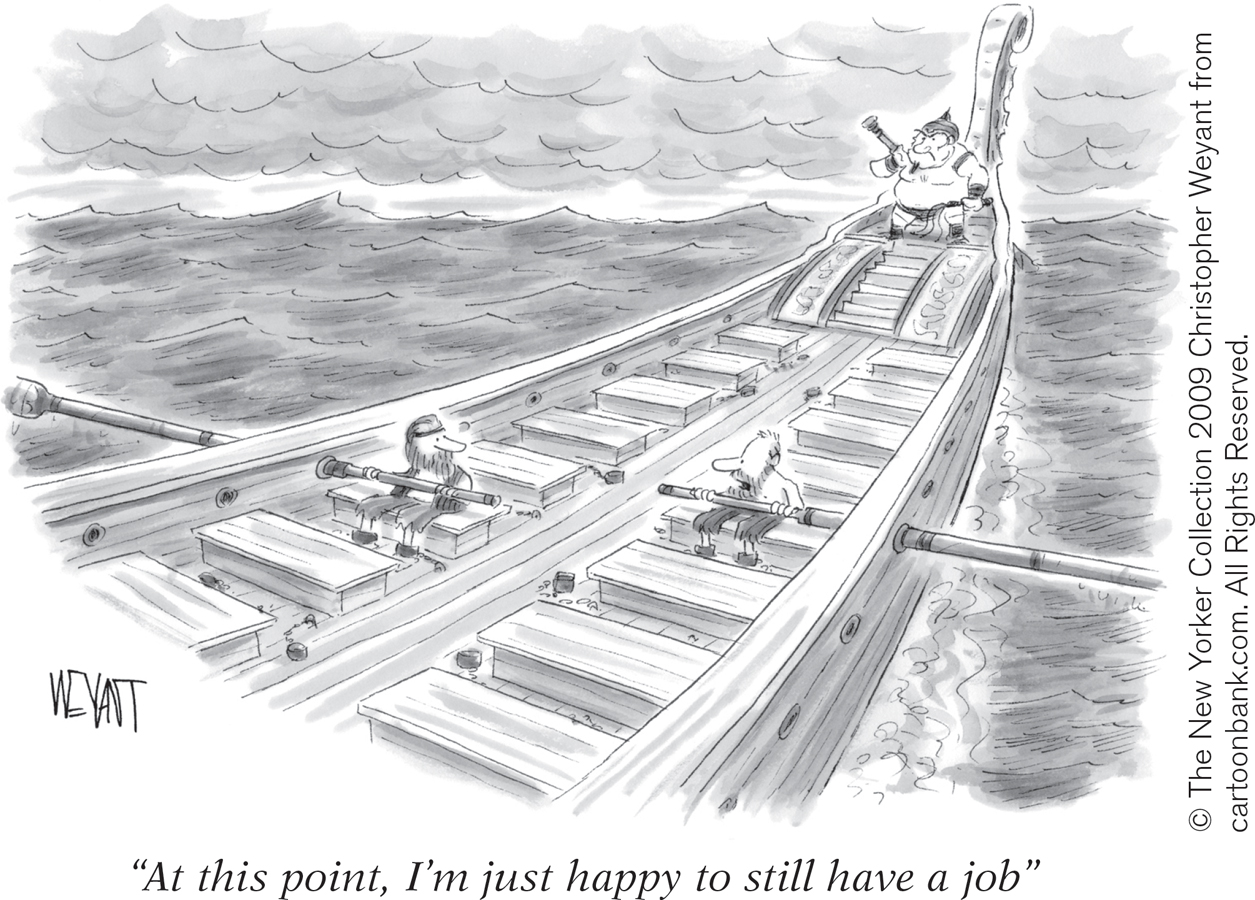

Continual job creation and destruction are a feature of modern economies, making a naturally occurring amount of unemployment inevitable. Within this naturally occurring amount, there are two types of unemployment—