Structural Unemployment

In structural unemployment, more people are seeking jobs in a particular labor market than there are jobs available at the current wage rate, even when the economy is at the peak of the business cycle.

Frictional unemployment exists even when the number of people seeking jobs is equal to the number of jobs being offered—that is, the existence of frictional unemployment doesn’t mean that there is a surplus of labor. Sometimes, however, there is a persistent surplus of job-seekers in a particular labor market, even when the economy is at the peak of the business cycle. There may be more workers with a particular skill than there are jobs available using that skill, or there may be more workers in a particular geographic region than there are jobs available in that region. Structural unemployment is unemployment that results when there are more people seeking jobs in a particular labor market than there are jobs available at the current wage rate.

The supply and demand model tells us that the price of a good, service, or factor of production tends to move toward an equilibrium level that matches the quantity supplied with the quantity demanded. This is equally true, in general, of labor markets.

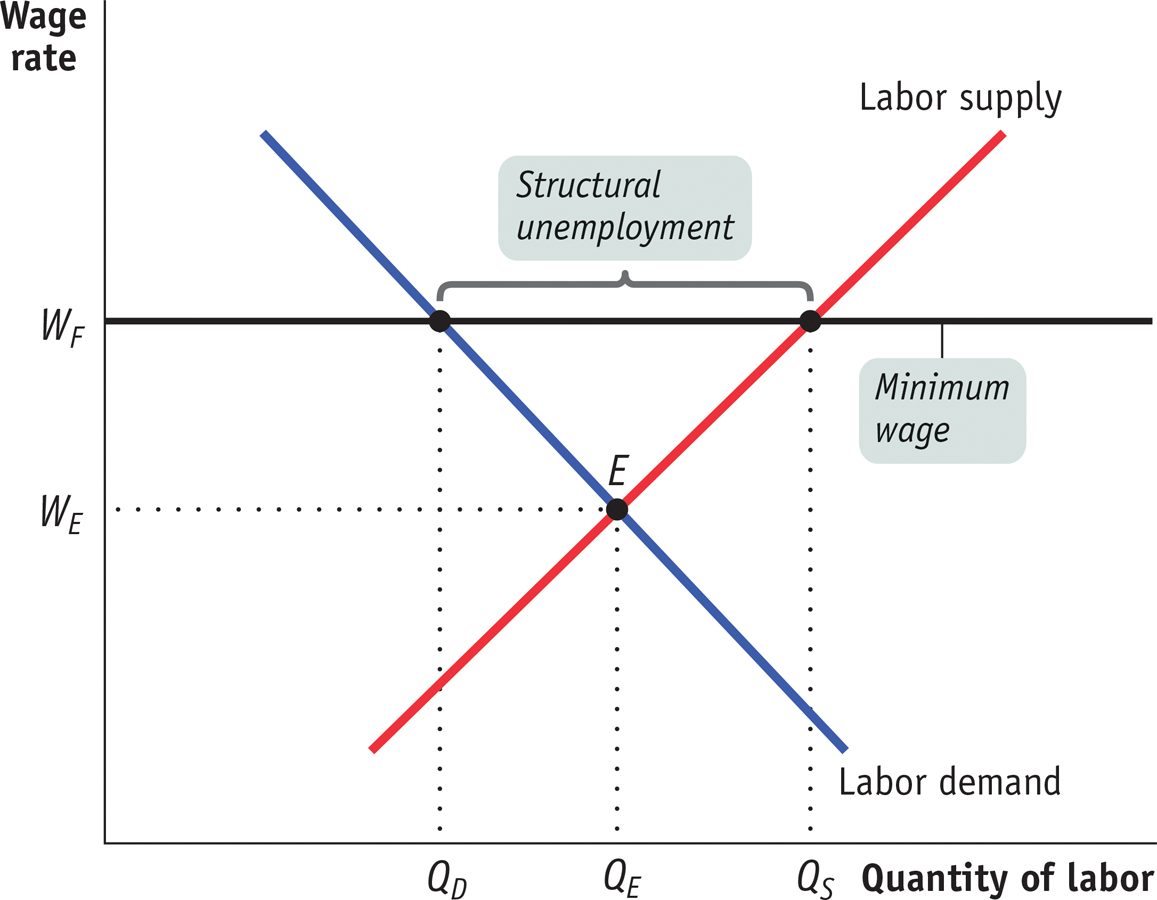

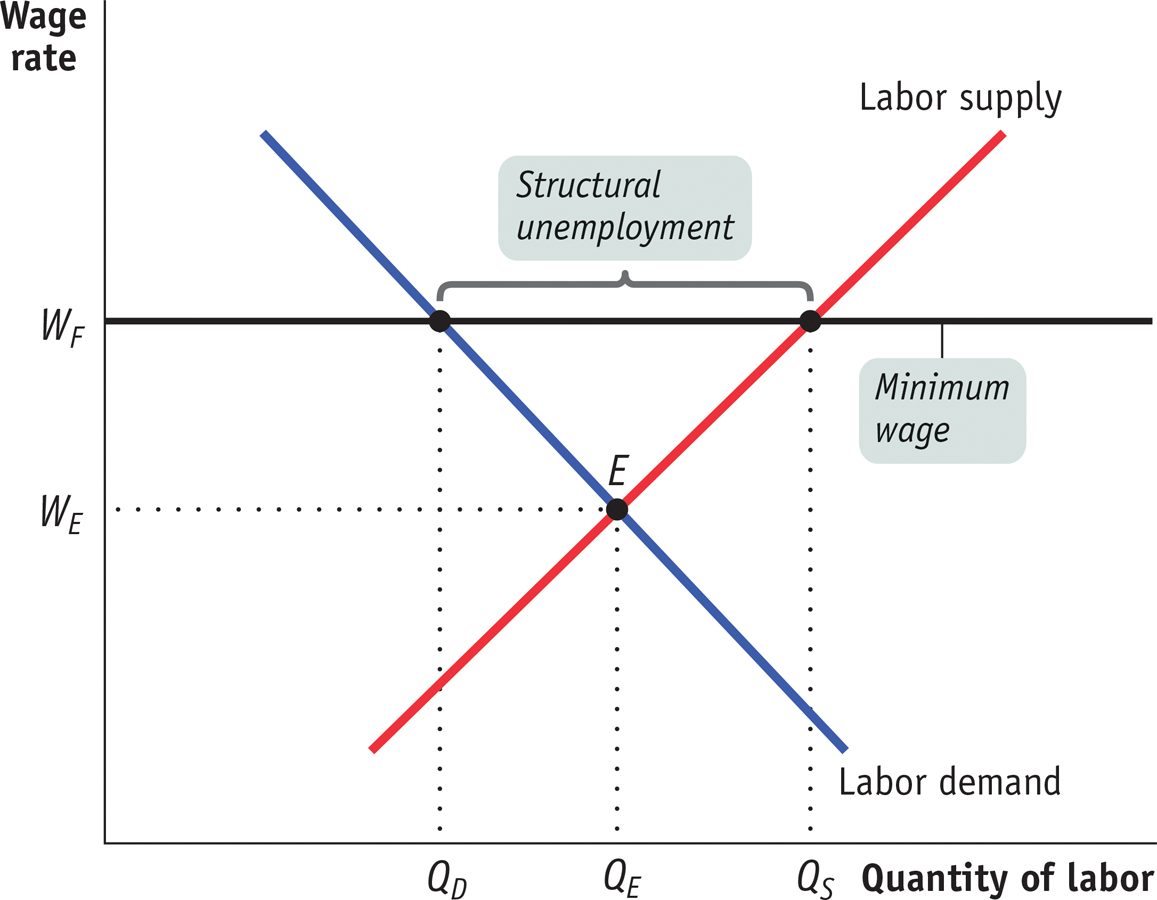

Figure 8-10 shows a typical market for labor. The labor demand curve indicates that when the price of labor—the wage rate—increases, employers demand less labor. The labor supply curve indicates that when the price of labor increases, more workers are willing to supply labor at the prevailing wage rate. These two forces coincide to lead to an equilibrium wage rate for any given type of labor in a particular location. That equilibrium wage rate is shown as WE.

The Effect of a Minimum Wage on a Labor Market When the government sets a minimum wage, WF, that exceeds the market equilibrium wage rate in that market, WE, the number of workers who would like to work at that minimum wage, QS, is greater than the number of workers demanded at that wage rate, QD. This surplus of labor is structural unemployment.

Even at the equilibrium wage rate WE, there will still be some frictional unemployment. That’s because there will always be some workers engaged in job search even when the number of jobs available is equal to the number of workers seeking jobs. But there wouldn’t be any structural unemployment in this labor market. Structural unemployment occurs when the wage rate is, for some reason, persistently above WE. Several factors can lead to a wage rate in excess of WE, the most important being minimum wages, labor unions, efficiency wages, the side effects of government policies, and mismatches between employees and employers.

Minimum Wages A minimum wage is a government-mandated floor on the price of labor. In the United States, the national minimum wage in early 2014 was $7.25 an hour. A number of state and local governments also determine the minimum wage within their jurisdictions, typically for the purpose of setting it higher than the federal level. For example, the city of Seattle has set a minimum wage at $15 an hour. For many American workers, the minimum wage is irrelevant; the market equilibrium wage for these workers is well above the national price floor. But for less skilled workers, the minimum wage may be binding—it affects the wages that people are actually paid and can lead to structural unemployment in particular markets for labor. Other wealthy countries have higher minimum wages; for example, in 2014 the French minimum wage was 9.40 euros an hour, or around $12.40. In these countries, the range of workers for whom the minimum wage is binding is larger.

Figure 8-10 shows the effect of a binding minimum wage. In this market, there is a legal floor on wages, WF, which is above the equilibrium wage rate, WE. This leads to a persistent surplus in the labor market: the quantity of labor supplied, QS, is larger than the quantity demanded, QD. In other words, more people want to work than can find jobs at the minimum wage, leading to structural unemployment.

Given that minimum wages—that is, binding minimum wages—generally lead to structural unemployment, you might wonder why governments impose them. The rationale is to help ensure that people who work can earn enough income to afford at least a minimally comfortable lifestyle. However, this may come at a cost, because it may eliminate the opportunity to work for some workers who would have willingly worked for lower wages. As illustrated in Figure 8-10, not only are there more sellers of labor than there are buyers, but there are also fewer people working at a minimum wage (QD) than there would have been with no minimum wage at all (QE).

Although economists broadly agree that a high minimum wage has the employment-reducing effects shown in Figure 8-10, there is some question about whether this is a good description of how the U.S. minimum wage actually works. The minimum wage in the United States is quite low compared with that in other wealthy countries. For three decades, from the 1970s to the mid-2000s, the American minimum wage was so low that it was not binding for the vast majority of workers.

In addition, some researchers have produced evidence showing that increases in the minimum wage actually lead to higher employment when, as was the case in the United States at one time, the minimum wage is low compared to average wages. They argue that firms that employ low-skilled workers sometimes restrict their hiring in order to keep wages low and that, as a result, the minimum wage can sometimes be increased without any loss of jobs. Most economists, however, agree that a sufficiently high minimum wage does lead to structural unemployment.

Labor Unions The actions of labor unions can have effects similar to those of minimum wages, leading to structural unemployment. By bargaining collectively for all of a firm’s workers, unions can often win higher wages from employers than workers would have obtained by bargaining individually. This process, known as collective bargaining, is intended to tip the scales of bargaining power more toward workers and away from employers. Labor unions exercise bargaining power by threatening firms with a labor strike, a collective refusal to work. The threat of a strike can have serious consequences for firms. In such cases, workers acting collectively can exercise more power than they could if acting individually.

Employers have acted to counter the bargaining power of unions by threatening and enforcing lockouts—periods in which union workers are locked out and rendered unemployed—while hiring replacement workers.

When workers have increased bargaining power, they tend to demand and receive higher wages. Unions also bargain over benefits, such as health care and pensions, which we can think of as additional wages. Indeed, economists who study the effects of unions on wages find that unionized workers earn higher wages and more generous benefits than non-union workers with similar skills. The result of these increased wages can be the same as the result of a minimum wage: labor unions push the wage that workers receive above the equilibrium wage. Consequently, there are more people willing to work at the wage being paid than there are jobs available. Like a binding minimum wage, this leads to structural unemployment. In the United States, however, due to a low level of unionization, the amount of unemployment generated by union demands is likely to be very small.

Efficiency wages are wages that employers set above the equilibrium wage rate as an incentive for better employee performance.

Efficiency Wage Actions by firms can contribute to structural unemployment. Firms may choose to pay efficiency wages—wages that employers set above the equilibrium wage rate as an incentive for their workers to perform better.

Employers may feel the need for such incentives for several reasons. For example, employers often have difficulty observing directly how hard an employee works. They can, however, elicit more work effort by paying above-market wages: employees receiving these higher wages are more likely to work harder to ensure that they aren’t fired, which would cause them to lose their higher wages.

When many firms pay efficiency wages, the result is a pool of workers who want jobs but can’t find them. So the use of efficiency wages by firms leads to structural unemployment.

Side Effects of Government Policies In addition, government policies designed to help workers who lose their jobs can lead to structural unemployment as an unintended side effect. Most economically advanced countries provide benefits to laid-off workers as a way to tide them over until they find a new job. In the United States, these benefits typically replace only a small fraction of a worker’s income and expire after 26 weeks. (This was extended in some cases to 99 weeks during the period of high unemployment in 2009–2011). In other countries, particularly in Europe, benefits are more generous and last longer. The drawback to this generosity is that it reduces a worker’s incentive to quickly find a new job. During the 1980s, it was often argued that unemployment benefits in some European countries were one of the causes of Eurosclerosis, persistently high unemployment that afflicts a number of European economies.

Mismatches Between Employees and Employers It takes time for workers and firms to adjust to shifts in the economy. The result can be a mismatch between what employees have to offer and what employers are looking for. A skills mismatch is one form; for example, in the aftermath of the housing bust of 2009, there were more construction workers looking for jobs than were available. Another form is geographic as in Michigan, which has had a long-standing surplus of workers after its auto industry declined. Until the mismatch is resolved through a big enough fall in wages of the surplus workers that induces retraining or relocation, there will be structural unemployment.