Natural Resources and Growth, Revisited

In 1972 a group of scientists called The Club of Rome made a big splash with a book titled The Limits to Growth, which argued that long-run economic growth wasn’t sustainable due to limited supplies of nonrenewable resources such as oil and natural gas. These “neo-Malthusian” concerns at first seemed to be validated by a sharp rise in resource prices in the 1970s, then came to seem foolish when resource prices fell sharply in the 1980s. After 2005, however, resource prices rose sharply again, leading to renewed concern about resource limitations to growth.

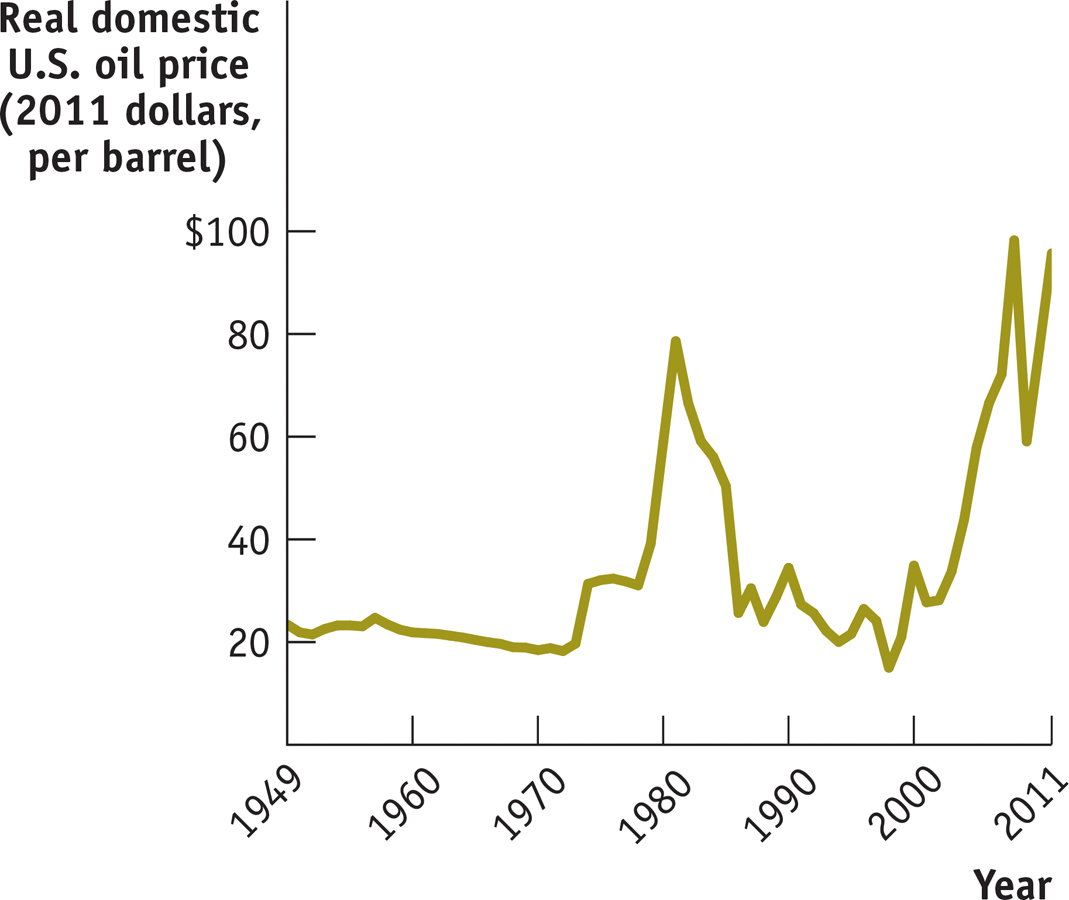

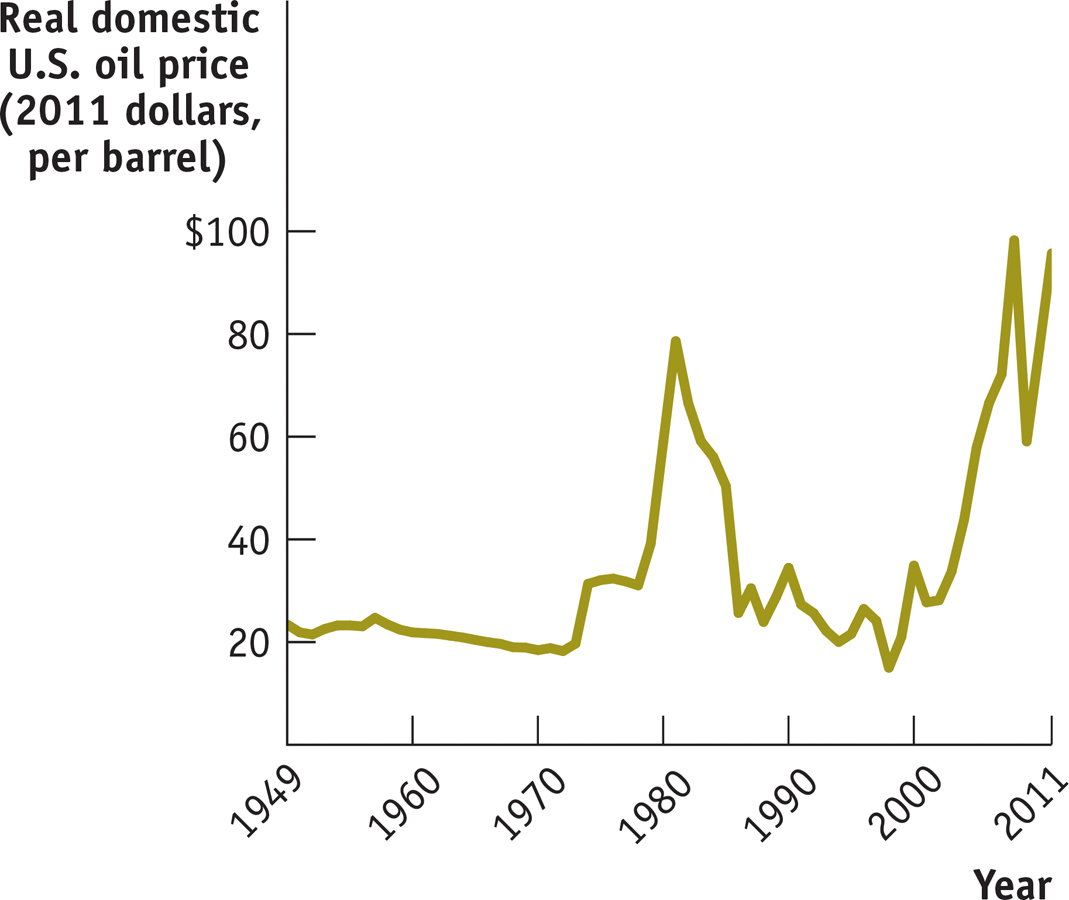

Figure 9-10 shows the real price of oil—the price of oil adjusted for inflation in the rest of the economy. The rise, fall, and rise of concern about resource-based limits to growth have more or less followed the rise, fall, and rise of oil prices shown in the figure.

The Real Price of Oil, 1949–2011 The real price of natural resources, like oil, rose dramatically in the 1970s and then fell just as dramatically in the 1980s. Since 2005, however, the real prices of natural resources have soared. Source: Energy Information Administration.

Differing views about the impact of limited natural resources on long-run economic growth turn on the answers to three questions:

How large are the supplies of key natural resources?

How effective will technology be at finding alternatives to natural resources?

Can long-run economic growth continue in the face of resource scarcity?

It’s mainly up to geologists to answer the first question. Unfortunately, there’s wide disagreement among the experts, especially about the prospects for future oil production. Some analysts believe that there is enough untapped oil in the ground that world oil production can continue to rise for several decades. Others, including a number of oil company executives, believe that the growing difficulty of finding new oil fields will cause oil production to plateau—that is, stop growing and eventually begin a gradual decline—in the fairly near future. Some analysts believe that we have already reached that plateau.

The answer to the second question, whether there are alternatives to natural resources, has to come from engineers. There’s no question that there are many alternatives to the natural resources currently being depleted, some of which are already being exploited. Indeed, since around 2005 there have been dramatic developments in energy production, with large amounts of previously unreachable oil and gas extracted through fracking, and with a huge decline in the cost of electricity generated by wind and especially solar power.

The third question, whether economies can continue to grow in the face of resource scarcity, is mainly a question for economists. And most, though not all, economists are optimistic: they believe that modern economies can find ways to work around limits on the supply of natural resources. One reason for this optimism is the fact that resource scarcity leads to high resource prices. These high prices in turn provide strong incentives to conserve the scarce resource and to find alternatives.

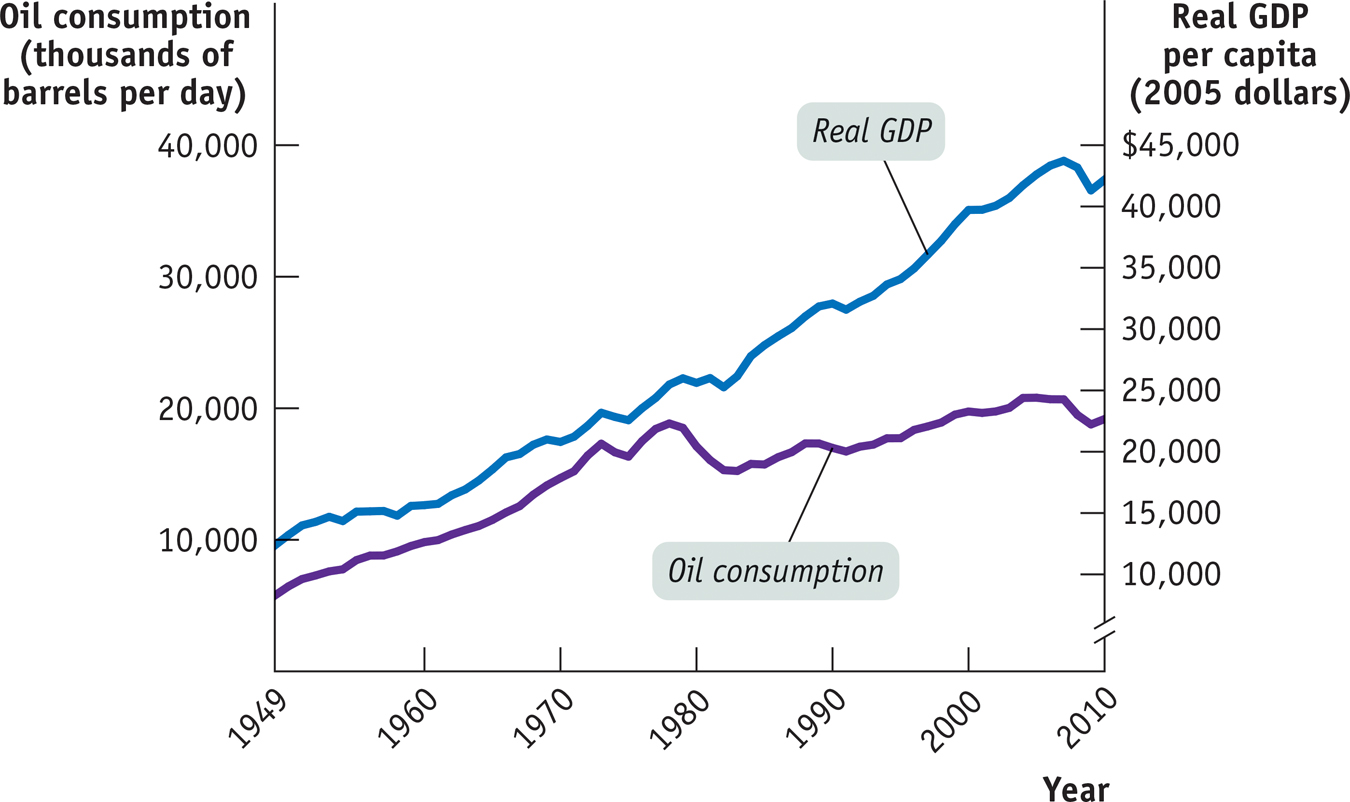

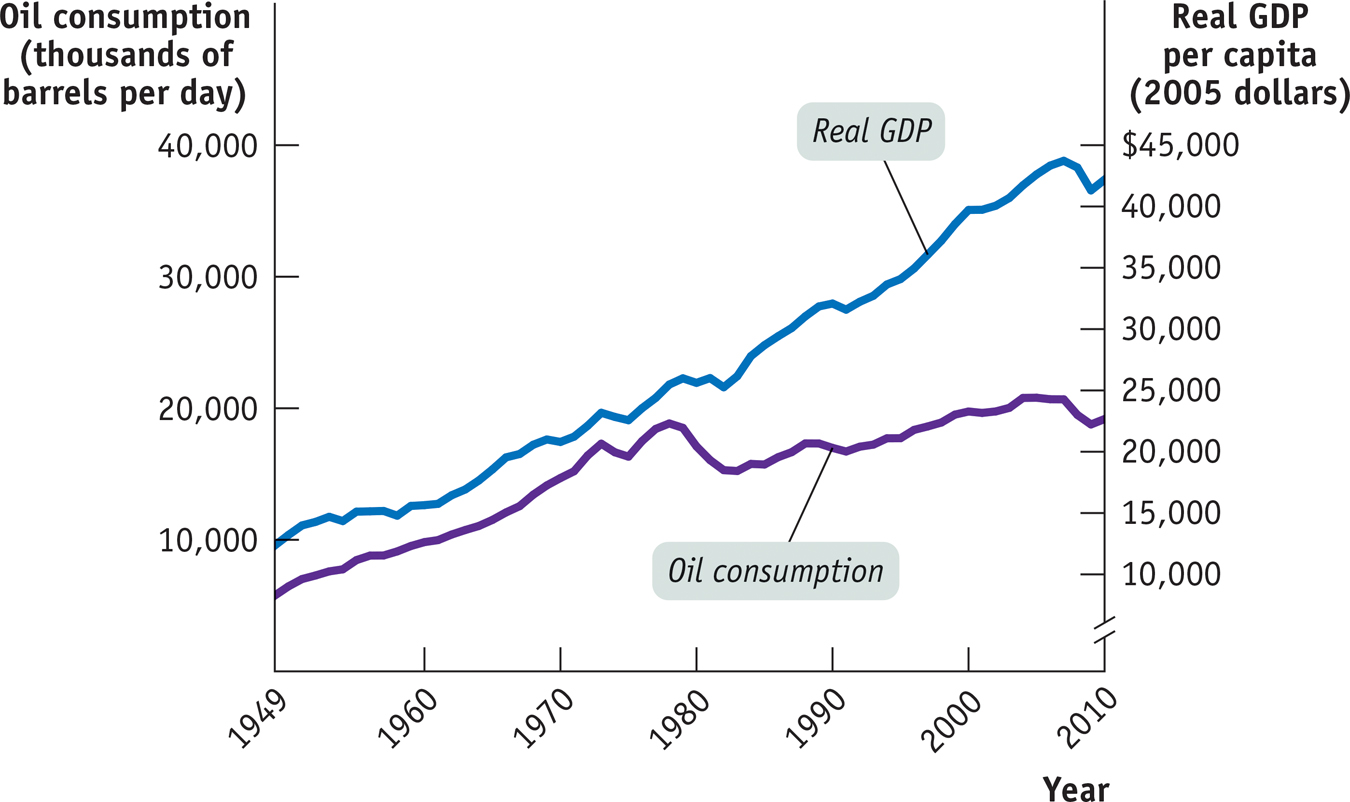

For example, after the sharp oil price increases of the 1970s, American consumers turned to smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, and U.S. industry also greatly intensified its efforts to reduce energy bills. The result is shown in Figure 9-11, which compares U.S. real GDP per capita and oil consumption before and after the 1970s energy crisis. In the United States before 1973 there seemed to be a more or less one-to-one relationship between economic growth and oil consumption. But after 1973 the U.S. economy continued to deliver growth in real GDP per capita even as it substantially reduced the use of oil.

U.S. Oil Consumption and Growth over Time Until 1973, the real price of oil was relatively cheap and there was a more or less one-to-one relationship between economic growth and oil consumption. Conservation efforts increased sharply after the spike in the real price of oil in the mid-1970s. Yet the U.S. economy was still able to deliver growth despite cutting back on oil consumption. Sources: Energy Information Administration; FRED; Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This move toward conservation paused after 1990, as low real oil prices encouraged consumers to shift back to gas-greedy larger cars and SUVs. But a sharp rise in oil prices from 2005 to 2008, and again in 2010, encouraged renewed shifts toward oil conservation.

Given such responses to prices, economists generally tend to see resource scarcity as a problem that modern economies handle fairly well, and so not a fundamental limit to long-run economic growth. Environmental issues, however, pose a more difficult problem because dealing with them requires effective political action.