1.2 29Monopoly and Public Policy

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The effects of the difference between perfect competition and monopoly on society’s welfare

The effects of the difference between perfect competition and monopoly on society’s welfare

How policy makers address the problems posed by monopoly

How policy makers address the problems posed by monopoly

It’s good to be a monopolist, but it’s not so good to be a monopolist’s customer. A monopolist, by reducing output and raising prices, benefits at the expense of consumers. But buyers and sellers always have conflicting interests. Is the conflict of interest under monopoly any different from what it is under perfect competition?

The answer is yes, because monopoly is a source of inefficiency: the losses to consumers from monopoly behavior are larger than the gains to the monopolist. Because monopoly leads to net losses for the economy, governments often try to adopt policies that either prevent the emergence of monopolies or limit their effects. In this module, we will see why monopoly leads to inefficiency and examine the policies governments turn to in response.

Welfare Effects of Monopoly

By holding output below the level at which marginal cost is equal to the market price, a monopolist increases its profit but hurts consumers. To assess whether this is a net benefit or loss to society, we must compare the monopolist’s gain in profit to the consumers’ loss. And what we learn is that the consumers’ loss is larger than the monopolist’s gain. Monopoly causes a net loss for society.

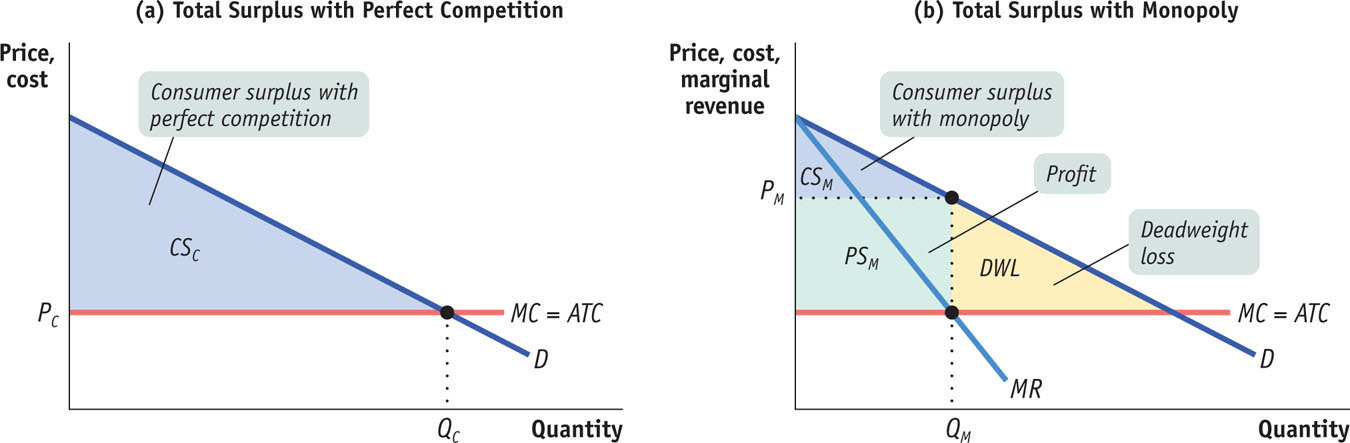

To see why, let’s return to the case in which the marginal cost curve is horizontal, as shown in the two panels of Figure 29-1. Here the marginal cost curve is MC, the demand curve is D, and, in panel (b), the marginal revenue curve is MR.

FIGURE29-1Monopoly Causes Inefficiency

Panel (a) shows what happens if this industry is perfectly competitive. Equilibrium output is QC; the price of the good, PC, is equal to marginal cost, and marginal cost is also equal to average total cost because there is no fixed cost and marginal cost is constant. Each firm is earning exactly its average total cost per unit of output, so there is no producer surplus in this equilibrium. The consumer surplus generated by the market is equal to the area of the blue-

Panel (b) shows the results for the same market, but this time as suming that the industry is a monopoly. The monopolist produces the level of output, QM, at which marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue, and it charges the price, PM. The industry now earns profit—

By comparing panels (a) and (b), we see that in addition to the redistribution of surplus from consumers to the monopolist, another important change has occurred: the sum of profit and consumer surplus—

Previously, we analyzed how taxes could cause deadweight loss for society. Here we show that a monopoly creates deadweight loss equal to the area of the yellow triangle, DWL. So monopoly produces a net loss for society.

This net loss arises because some mutually beneficial transactions do not occur. There are people for whom an additional unit of the good is worth more than the marginal cost of producing it but who don’t consume it because they are not willing to pay the monopoly price, PM. Indeed, by driving a wedge between price and marginal cost, a monopoly acts much like a tax on consumers and produces the same kind of inefficiency.

So monopoly power detracts from the welfare of society as a whole and is a source of market failure. Is there anything government policy can do about it?

Preventing Monopoly

Policy toward monopolies depends crucially on whether or not the industry in question is a natural monopoly. As you know, a natural monopoly is one in which increasing returns to scale ensure that a bigger producer has lower average total cost. If the industry is not a natural monopoly, the best policy is to prevent a monopoly from arising or break it up if it already exists.

Dealing with a Natural Monopoly

Breaking up a monopoly that isn’t natural is clearly a good idea: the gains to consumers outweigh the loss to the producer. But it’s not so clear whether a natural monopoly, one in which large producers have lower average total costs than small producers, should be broken up, because this would raise average total cost. For example, a town government that tried to prevent a single company from dominating local gas supply—

Yet even in the case of a natural monopoly, a profit-

What can public policy do about this? There are two common answers:

- Public ownership

- Regulation

Public Ownership

In public ownership of a monopoly, the good is supplied by the government or by a firm owned by the government.

In many countries, the preferred answer to the problem of natural monopoly has been public ownership. Instead of allowing a private monopolist to control an industry, the government establishes a public agency to provide the good and protect consumers’ interests.

There are some examples of public ownership in the United States. Passenger rail service is provided by the public company Amtrak; regular mail delivery is provided by the U.S. Postal Service; some cities, including Los Angeles, have publicly owned electric power companies.

The advantage of public ownership, in principle, is that a publicly owned natural monopoly can set prices based on the criterion of efficiency rather than profit maximization. In a perfectly competitive industry, profit-

Experience suggests, however, that public ownership as a solution to the problem of natural monopoly often works badly in practice. One reason is that publicly owned firms are often less eager than private companies to keep costs down or offer high-

Regulation

Price regulation limits the price that a monopolist is allowed to charge.

In the United States, the more common answer to the existence of natural monopolies has been to leave the industry in private hands but subject it to regulation. In particular, most local utilities, like electricity, telephone service, natural gas, and so on, are covered by price regulation that limits the prices they can charge.

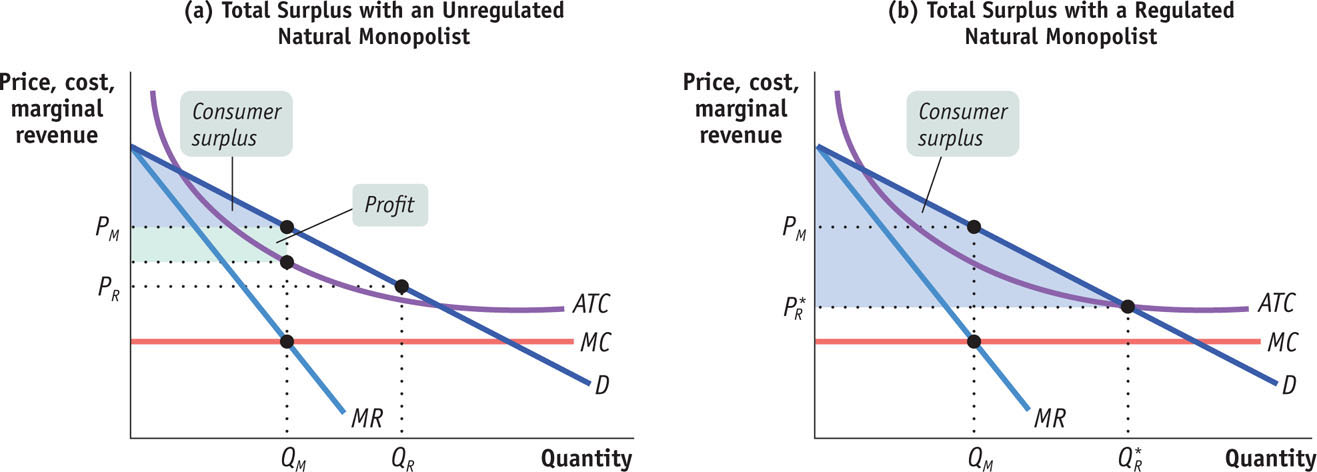

Figure 29-2 shows an example of price regulation of a natural monopoly—

FIGURE29-2Unregulated and Regulated Natural Monopoly

. Output expands to

. Output expands to  , and consumer surplus is now the entire blue area. The monopolist makes zero profit. This is the greatest total surplus possible without the monopoly incurring losses.

, and consumer surplus is now the entire blue area. The monopolist makes zero profit. This is the greatest total surplus possible without the monopoly incurring losses.

Panel (a) illustrates a case of natural monopoly without regulation. The unregulated natural monopolist chooses the monopoly output QM and charges the price PM. Since the monopolist receives a price greater than average total cost, it earns a profit, represented by the green-

Now suppose that regulators impose a price ceiling on local gas deliveries—

Does the company have an incentive to produce that quantity? Yes. If the price the monopolist can charge is fixed at PR by regulators, the firm can sell any quantity between zero and QR for the same price, PR. Because it doesn’t have to lower its price to sell more (up to QR), there is no price effect to bring marginal revenue below price, so the regulated price becomes the marginal revenue for the monopoly just like the market price is the marginal revenue for a perfectly competitive firm. With marginal revenue being above marginal cost and price exceeding average cost, the firm expands output to meet the quantity demanded, QR. This policy has appeal because at the regulated price, the monopolist produces more at a lower price.

Of course, the monopolist will not be willing to produce at all in the long run if the regulated price means producing at a loss. That is, the price ceiling has to be set high enough to allow the firm to cover its average total cost. Panel (b) shows a situation in which regulators have pushed the price down as far as possible, at the level where the average total cost curve crosses the demand curve. At any lower price the firm loses money. The price here,  , is the best regulated price: the monopolist is just willing to operate because profits are zero and produces

, is the best regulated price: the monopolist is just willing to operate because profits are zero and produces  , the quantity demanded at that price. Consumers and society gain as a result.

, the quantity demanded at that price. Consumers and society gain as a result.

The welfare effects of this regulation can be seen by comparing the shaded areas in the two panels of Figure 29-2. Consumer surplus is increased by the regulation, with the gains coming from two sources. First, profits are eliminated and added instead to consumer surplus. Second, the larger output and lower price leads to an overall welfare gain—

Must Monopoly Be Controlled?

Sometimes the cure is worse than the disease. Some economists have argued that the best solution, even in the case of a natural monopoly, may be to live with it. The case for doing nothing is that attempts to control monopoly will, one way or another, do more harm than good.

The following Economics in Action describes the case of cable television, a natural monopoly that has been alternately regulated and deregulated as politicians change their minds about the appropriate policy.

CHAINED BY YOUR CABLE

The old saying “you can’t escape death and taxes” now has a modern twist: “you can’t escape death, taxes, and cable price increases.” Over the last 10 years consumers have seen their cable prices increase by around 3% every year, an amount exceeding the rate of inflation.

Until 1984, cable prices were regulated locally. Because running a cable through a town entailed large fixed costs, cable TV was considered a natural monopoly. However, in 1984 Congress passed a law prohibiting most local governments from regulating cable prices. The result: prices increased sharply, and in 1992 the ensuing consumer backlash led to a new law that once again allowed local governments to set limits on cable prices. But cable operators found ways to circumvent the restrictions.

What went wrong? One possible explanation is that the 1992 law applied only to “basic” packages, and those prices did indeed level off. In response, cable operators began offering fewer channels in the basic package and charging more for premium channels like HBO.

Cable operators have defended their pricing policies, claiming they have been forced to pay higher prices to content providers for popular shows. For example, Time Warner Cable and the Fox network fought fiercely when their contract ended in late 2009, with Fox demanding to be paid $1 per subscriber to their content. When a deal was reached, it was reported that Time Warner had agreed to pay Fox more than 50 cents per subscriber.

Yet critics counter that this defense is largely invalid because about 40% of the channels that command the highest prices are owned in whole or in part by the cable operators themselves. So in paying high prices for content, cable operators are actually profiting.

Cable operators also claim they need to raise prices to pay for system upgrades. Critics, however, once again dismiss the claim, asserting that upgrades pay for themselves through premium pricing and so should not have any effect on the price of non-

Critics also point to evidence that cable operators are exploiting their monopoly power. For example, a study by the Federal Communications Commission showed that cable operators have increased their take per subscriber by over 30% after factoring out all operating costs, including the cost of content. Similarly, the General Accounting Office found that prices are on average 17% lower in communities with two cable operators compared to one.

TV-

29

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. What policy should the government adopt in the following cases? Explain.

-

a. Internet service in Anytown, OH, is provided by cable. Customers feel they are being overcharged, but the cable company claims it must charge prices that let it recover the costs of laying cable.

Cable Internet service is a natural monopoly. So the government should intervene if it believes that the current price exceeds average total cost, which includes the cost of laying the cable. In this case it should impose a price ceiling equal to average total cost. If the price does not exceed average total cost, the government should do nothing. -

b. The only two airlines that currently fly to Alaska need government approval to merge. Other airlines wish to fly to Alaska but need government-

allocated landing slots to do so. The government should approve the merger only if it fosters competition by transferring some of the company’s landing slots to another, competing airline.

2. True or false? Explain your answer.

-

a. Society’s welfare is lower under monopoly because some consumer surplus is transformed into profit for the monopolist.

False. Although some consumer surplus is indeed transformed into monopoly profit, this is not the source of inefficiency. As can be seen from Figure 29-1, panel (b), the inefficiency arises from the fact that some of the consumer surplus is transformed into deadweight loss (the yellow area), which is a complete loss not captured by consumers, producers, or anyone else. -

b. A monopolist causes inefficiency because there are consumers who are willing to pay a price greater than or equal to marginal cost but less than the monopoly price.

True. If a monopolist sold to all customers willing to pay an amount greater than or equal to marginal cost, all mutually beneficial transactions would occur and there would be no deadweight loss.

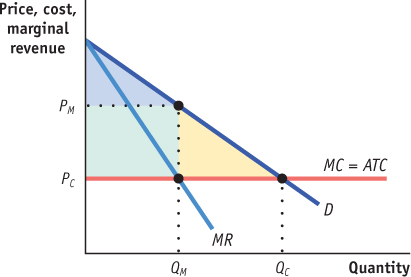

3. Suppose a monopolist mistakenly believes that its marginal revenue is always equal to the market price. Assuming constant marginal cost and no fixed cost, draw a diagram comparing the level of profit, consumer surplus, total surplus, and deadweight loss for this misguided monopolist compared to a smart monopolist. Explain your findings.

Multiple-

Question

1. Which of the following statements is true of a monopoly as compared to a perfectly competitive market with the same costs?

I. Consumer surplus is smaller.

II. Profit is smaller.

III. Deadweight loss is smaller.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. Which of the following is true of a natural monopoly?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Which of the following government actions is the most common for a natural monopoly in the United States?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

4. Which of the following markets is an example of a regulated natural monopoly?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. Which of the following is most likely to be higher for a regulated natural monopoly than for an unregulated natural monopoly?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

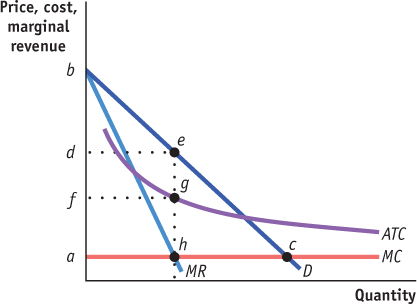

1. Draw a correctly labeled graph of a natural monopoly. Use your graph to identify each of the following:

a. consumer surplus if the market were somehow able to operate as a perfectly competitive market

triangle bcab. consumer surplus with the monopoly

triangle bedc. monopoly profit

rectangle degfd. deadweight loss with the monopoly

triangle ech