1.5 35Product Differentiation and Advertising

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

Why oligopolists and monopolistic competitors differentiate their products

Why oligopolists and monopolistic competitors differentiate their products

The economic significance of advertising and brand names

The economic significance of advertising and brand names

In previous modules we learned that product differentiation often plays an important role in oligopolistic industries. In such industries, product differentiation reduces the intensity of competition between firms when tacit collusion cannot be achieved. It plays an even more crucial role in monopolistically competitive industries. Because tacit collusion is virtually impossible when there are many producers, product differentiation is the only way monopolistically competitive firms can acquire some market power.

In this module, we look at how oligopolists and monopolistic competitors differentiate their products in order to maximize profits.

How Firms Differentiate Their Products

How do firms in the same industry—

The key to product differentiation is that consumers have different preferences and are willing to pay somewhat more to satisfy those preferences. Each producer can carve out a market niche by producing something that caters to the particular preferences of some group of consumers better than the products of other firms. There are three important forms of product differentiation:

- differentiation by style or type

- differentiation by location

- differentiation by quality.

Differentiation by Style or Type

Recall our discussion of Leo’s Wonderful Wok in an earlier module. The sellers in Leo’s food court offer different types of fast food: hamburgers, pizza, Chinese food, Mexican food, and so on. Each consumer arrives at the food court with some preference for one or another of these offerings. This preference may depend on the consumer’s mood, her diet, or what she has already eaten that day. These preferences will not make consumers indifferent to price: if Wonderful Wok were to charge $15 for an egg roll, everybody would go to Bodacious Burgers or Pizza Paradise instead. But some people will choose a more expensive meal if that type of food is closer to their preference. So the products of the different vendors are substitutes, but they aren’t perfect substitutes—

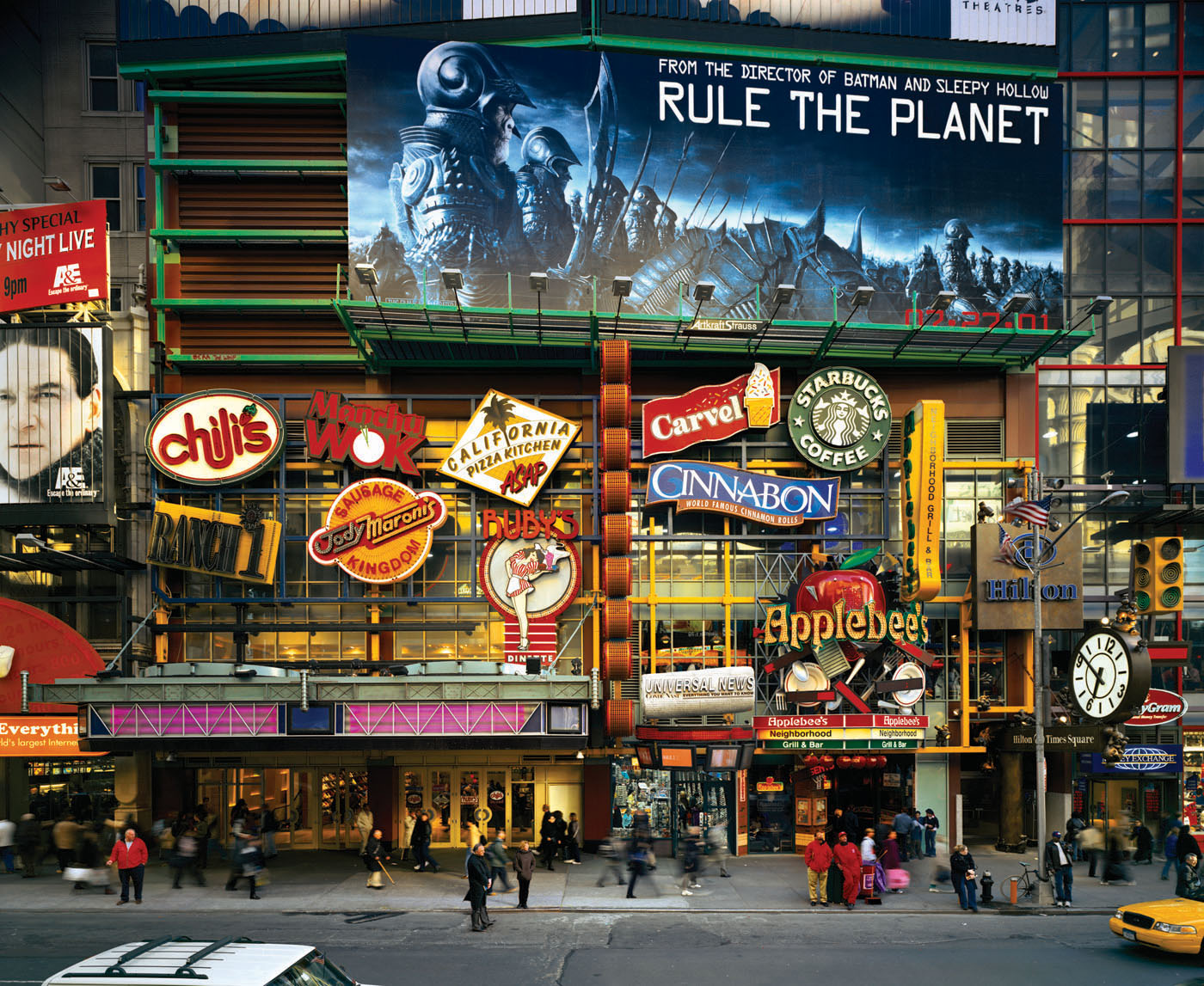

Vendors in a food court or the restaurant chains in Times Square (shown in the photo at left) aren’t the only sellers who differentiate their offerings by type. Clothing stores concentrate on women’s or men’s clothes, on business attire or sportswear, on trendy or classic styles, and so on. Auto manufacturers offer sedans, minivans, sport-

Books offer yet another example of differentiation by type and style. Mysteries are differentiated from romances; among mysteries, we can differentiate among hard-

In fact, product differentiation is characteristic of most consumer goods. As long as people differ in their tastes, producers find it possible and profitable to offer variety.

Differentiation by Location

Gas stations along a road offer differentiated products. True, the gas may be exactly the same. But the location of the stations is different, and location matters to consumers: it’s more convenient to stop for gas near your home, near your workplace, or near wherever you are when the gas gauge gets low.

In fact, many monopolistically competitive industries supply goods differentiated by location. This is especially true in service industries, from dry cleaners to hairdressers, where customers often choose the seller who is closest rather than cheapest.

Differentiation by Quality

Do you have a craving for chocolate? How much are you willing to spend on it? You see, there’s chocolate and then there’s chocolate: although ordinary chocolate may not be very expensive, gourmet chocolate can cost several dollars per bite.

With chocolate, as with many goods, there is a range of possible qualities. You can get a usable bicycle for less than $100; you can get a much fancier bicycle for 10 times as much. It all depends on how much the additional quality matters to you and how much you will miss the other things you could have purchased with that money.

Because consumers vary in what they are willing to pay for higher quality, producers can differentiate their products by quality—

Product differentiation, then, can take several forms. Whatever form it takes, however, there are two important features of industries with differentiated products: competition among sellers and value in diversity.

Competition among sellers means that even though sellers of differentiated products are not offering identical goods, they are to some extent competing for a limited market. If more businesses enter the market, each will find that it sells a lower quantity at any given price. For example, as we saw in the previous chapter, if a new gas station opens along a road, each of the existing gas stations will sell a bit less.

Value in diversity refers to the gain to consumers from the proliferation of differentiated products. A food court with eight vendors makes consumers happier than one with only six vendors, even if the prices are the same, because some customers will get a meal that is closer to what they had in mind. A road on which there is a gas station every two miles is more convenient for motorists than a road where gas stations are five miles apart. When a product is available in many different qualities, fewer people are forced to pay for more quality than they need or to settle for lower quality than they want. There are, in other words, benefits to consumers from a greater diversity of available products.

ANY COLOR, SO LONG AS IT’S BLACK

The early history of the auto industry offers a classic illustration of the power of product differentiation.

The modern automobile industry was created by Henry Ford, who first introduced assembly-

Ford’s strategy was to offer just one style of car, which maximized his economies of scale in production but made no concessions to differences in consumers’ tastes. He supposedly declared that customers could get the Model T in “any color, so long as it’s black.”

This strategy was challenged by Alfred P. Sloan, who had merged a number of smaller automobile companies into General Motors. Sloan’s strategy was to offer a range of car types, differentiated by quality and price. Chevrolets were basic cars that directly challenged the Model T, Buicks were bigger and more expensive, and so on up to Cadillacs. And you could get each model in several different colors.

By the 1930s the verdict was clear: customers preferred a range of styles, and General Motors, not Ford, became the dominant auto manufacturer for the rest of the twentieth century.

Controversies About Product Differentiation

Up to this point, we have assumed that products are differentiated in a way that corresponds to some real desire of consumers. There is real convenience in having a gas station in your neighborhood; Chinese food and Mexican food are really different from each other.

In the real world, however, some instances of product differentiation can seem puzzling if you think about them. What is the real difference between Crest and Colgate toothpaste? Between Energizer and Duracell batteries? Or a Marriott and a Hilton hotel room? Most people would be hard-

No discussion of product differentiation is complete without spending at least a bit of time on the two related issues—

The Role of Advertising

Wheat farmers don’t advertise their wares on TV, but car dealers do. That’s not because farmers are shy and car dealers are outgoing; it’s because advertising is worthwhile only in industries in which firms have at least some market power.

The purpose of advertisements is to persuade people to buy more of a seller’s product at the going price. A perfectly competitive firm, which can sell as much as it likes at the going market price, has no incentive to spend money persuading consumers to buy more. Only a firm that has some market power, and which therefore charges a price that is above marginal cost, can gain from advertising. Some industries that are more or less perfectly competitive, like the milk industry, do advertise—

Given that advertising “works,” it’s not hard to see why firms with market power would spend money on it. But the big question about advertising is, why does it work? A related question is whether advertising is, from society’s point of view, a waste of resources.

Not all advertising poses a puzzle. Much of it is straightforward: it’s a way for sellers to inform potential buyers about what they have to offer (or, occasionally, for buyers to inform potential sellers about what they want). Nor is there much controversy about the economic usefulness of ads that provide information: the real estate ad that declares “sunny, charming, 2 bedrooms, 1 bath, a/c” tells you things you need to know (even if a few euphemisms are involved—

But what information is being conveyed when a TV actress proclaims the virtues of one or another toothpaste or a sports hero declares that some company’s batteries are better than those inside that pink mechanical rabbit? Surely nobody believes that the sports star is an expert on batteries—

Why are consumers influenced by ads that do not really provide any information about the product? One answer is that consumers are not as rational as economists typically assume. Perhaps consumers’ judgments, or even their tastes, can be influenced by things that economists think ought to be irrelevant, such as which company has hired the most charismatic celebrity to endorse its product. And there is surely some truth to this. Consumer rationality is a useful working assumption; it is not an absolute truth.

However, another answer is that consumer response to advertising is not entirely irrational because ads can serve as indirect “signals” in a world where consumers don’t have good information about products. Suppose, to take a common example, that you need to avail yourself of some local service that you don’t use regularly—

The same principle may partly explain why ads feature celebrities. You don’t really believe that the supermodel prefers that watch; but the fact that the watch manufacturer is willing and able to pay her fee tells you that it is a major company that is likely to stand behind its product. According to this reasoning, an expensive advertisement serves to establish the quality of a firm’s products in the eyes of consumers.

The possibility that it is rational for consumers to respond to advertising also has some bearing on the question of whether advertising is a waste of resources. If ads work by manipulating only the weak-

Brand Names

You’ve been driving all day, and you decide that it’s time to find a place to sleep. On your right, you see a sign for the Bates Motel; on your left, you see a sign for a Motel 6, or a Best Western, or some other national chain. Which one do you choose?

Unless they were familiar with the area, most people would head for the chain. In fact, most motels in the United States are members of major chains; the same is true of most fast-

brand name is a name owned by a particular firm that distinguishes its products from those of other firms.

Motel chains and fast-

In fact, companies often go to considerable lengths to defend their brand names, suing anyone else who uses them without permission. You may talk about blowing your nose on a kleenex or googling data for a research project, but unless the product in question comes from Kleenex or Google, legally the seller must describe it as a facial tissue or a search engine.

As with advertising, with which they are closely linked, the social usefulness of brand names is a source of dispute. Does the preference of consumers for known brands reflect consumer irrationality? Or do brand names convey real information? That is, do brand names create unnecessary market power, or do they serve a real purpose?

As in the case of advertising, the answer is probably some of both. On the one hand, brand names often do create unjustified market power. Consumers often pay more for brand-

On the other hand, for many products the brand name does convey information. A traveler arriving in a strange town can be sure of what awaits in a Holiday Inn or a McDonald’s; a tired and hungry traveler may find this preferable to trying an independent hotel or restaurant that might be better—

In addition, brand names offer some assurance that the seller is engaged in repeated interaction with its customers and so has a reputation to protect. If a traveler eats a bad meal at a restaurant in a tourist trap and vows never to eat there again, the restaurant owner may not care, since the chance is small that the traveler will be in the same area again in the future. But if that traveler eats a bad meal at McDonald’s and vows never to eat at a McDonald’s again, that matters to the company. This gives McDonald’s an incentive to provide consistent quality, thereby assuring travelers that quality controls are in place.

35

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. Each of the following goods and services is a differentiated product. Which are differentiated as a result of monopolistic competition and which are not? Explain your answers.

-

a. ladders

Ladders are not differentiated as a result of monopolistic competition. A ladder producer makes different ladders (tall ladders versus short ladders) to satisfy different consumer needs, not to avoid competition with rivals. So two tall ladders made by two different producers will be indistinguishable by consumers. -

b. soft drinks

Soft drinks are an example of product differentiation as a result of monopolistic competition. For example, several producers make colas; each is differentiated in terms of taste, which fast-food chains sell it, and so on. -

c. department stores

Department stores are an example of product differentiation as a result of monopolistic competition. They serve different clientele that have different price sensitivities and different tastes. They also offer different levels of customer service and are situated in different locations. -

d. steel

Steel is not differentiated as a result of monopolistic competition. Different types of steel (beams versus sheets) are made for different purposes, not to distinguish one steel manufacturer’s products from another’s.

2. You must determine which of two types of market structure better describes an industry, but you are allowed to ask only one question about the industry. What question should you ask to determine if an industry is

-

a. perfectly competitive or monopolistically competitive?

Perfectly competitive industries and monopolistically competitive industries both have many sellers. So it may be hard to distinguish between them solely in terms of number of firms. And in both market structures, there is free entry into and exit from the industry in the long run. But in a perfectly competitive industry, one standardized product is sold; in a monopolistically competitive industry, products are differentiated. So you should ask whether products are differentiated in the industry. -

b. a monopoly or monopolistically competitive?

In a monopoly there is only one firm, but a monopolistically competitive industry contains many firms. So you should ask whether or not there is a single firm in the industry.

3. For each of the following types of advertising, explain whether it is likely to be useful or wasteful from the standpoint of consumers.

-

a. advertisements explaining the benefits of aspirin

This type of advertising is likely to be useful because it provides new information on an important product. -

b. advertisements for Bayer aspirin

This type of advertising is likely to be wasteful because it is focused on promoting Bayer aspirin over a rival’s aspirin despite the two products being medically indistinguishable. -

c. advertisements that state how long a plumber or an electrician has been in business

This is useful because the longevity of a business gives a potential customer information about its quality.

4. Some industry analysts have stated that a successful brand name is like a barrier to entry. Explain why this might be true.

Multiple-

Question

1. Which of the following is a form of product differentiation?

I. style or type

II. location

III. quality

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. In which of the following market structures will individual firms advertise?

I. perfect competition

II. oligopoly

III. monopolistic competition

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Advertising is an attempt to affect which of the following?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

4. Brand names generally serve to

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. Which of the following is true of advertising expenditures in monopolistic competition? Monopolistic competitors

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

When is product differentiation socially efficient? Explain. When is it not socially efficient? Explain.