1.3 38Public Goods and Common Resources

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How public goods are characterized and why markets fail to supply efficient quantities of them

How public goods are characterized and why markets fail to supply efficient quantities of them

What common resources are and why they are overused

What common resources are and why they are overused

What artificially scarce goods are and why they are underconsumed

What artificially scarce goods are and why they are underconsumed

In this module, we take a somewhat different approach to the question of why markets sometimes fail. Here we focus on how the characteristics of goods often determine whether markets can deliver them efficiently. When goods have the “wrong” characteristics, the resulting market failures resemble those associated with externalities or market power.

This alternative way of looking at sources of inefficiency deepens our understanding of why markets sometimes don’t work well and how government can take actions that improve the welfare of society.

Private Goods—and Others

What’s the difference between installing a new bathroom in a house and building a municipal sewage system? What’s the difference between growing wheat and fishing in the open ocean?

These aren’t trick questions. In each case there is a basic difference in the characteristics of the goods involved. Bathroom appliances and wheat have the characteristics necessary to allow markets to work efficiently. Public sewage systems and fish in the sea do not.

Let’s look at these crucial characteristics and why they matter.

Characteristics of Goods

Goods like bathroom fixtures and wheat have two characteristics that are essential if a good is to be provided in efficient quantities by a market economy.

- They are excludable: suppliers of the good can prevent people who don’t pay from consuming it.

A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

- They are rival in consumption: the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good is rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is both excludable and rival in consumption, it is called a private good. Wheat is an example of a private good. It is excludable: the farmer can sell a bushel to one consumer without having to provide wheat to everyone in the county. And it is rival in consumption: if I eat bread baked with a farmer’s wheat, that wheat cannot be consumed by someone else.

When a good is nonexcludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

But not all goods possess these two characteristics. Some goods are nonexcludable—the supplier cannot prevent consumption of the good by people who do not pay for it. Fire protection is one example: a fire department that puts out fires before they spread protects the whole city, not just people who have made contributions to the Firemen’s Benevolent Association. An improved environment is another: pollution can’t be ended for some users of a river while leaving the river foul for others.

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

Nor are all goods rival in consumption. Goods are nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time. TV programs are nonrival in consumption: your decision to watch a show does not prevent other people from watching the same show.

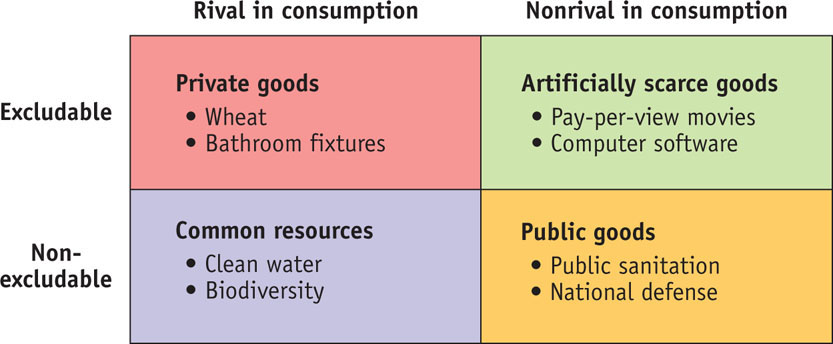

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, and either rival or nonrival in consumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by the matrix in Figure 38-1:

- Private goods, which are excludable and rival in consumption, like wheat

- Public goods, which are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, like a public sewer system

- Common resources, which are nonexcludable but rival in consumption, like clean water in a river

- Artificially scarce goods, which are excludable but nonrival in consumption, like on-

demand movies on satellite TV

FIGURE38-1Four Types of Goods

There are, of course, many other characteristics that distinguish between types of goods—

Why Markets Can Supply Only Private Goods Efficiently

As we learned in earlier modules, markets are typically the best means for a society to deliver goods and services to its members; that is, markets are efficient except in the case of market power, externalities, or other instances of market failure. One source of market failure is rooted in the nature of the good itself: markets cannot supply goods and services efficiently unless they are private goods—

To see why excludability is crucial, suppose that a farmer had only two choices: either produce no wheat or provide a bushel of wheat to every resident of the county who wants it, whether or not that resident pays for it. It seems unlikely that anyone would grow wheat under those conditions.

Yet the operator of a public sewage system faces pretty much the same problem as our hypothetical farmer. A sewage system makes the whole city cleaner and healthier—

Goods that are nonexcludable suffer from the free-

The general point is that if a good is nonexcludable, rational consumers won’t be willing to pay for it—

Because of the free-

Goods that are excludable and nonrival in consumption, like pay-

But if a satellite TV provider actually charges viewers $4, viewers will consume the good only up to the point where their marginal benefit is $4. When consumers must pay a price greater than zero for a good that is nonrival in consumption, the price they pay is higher than the marginal cost of allowing them to consume that good, which is zero. So in a market economy goods that are nonrival in consumption suffer from inefficiently low consumption.

Now we can see why private goods are the only goods that will be produced and consumed in efficient quantities in a competitive market. (That is, a private good will be produced and consumed in efficient quantities in a market free of market power, externalities, and other sources of market failure.) Because private goods are excludable, producers can charge for them and so have an incentive to produce them. And because they are also rival in consumption, it is efficient for consumers to pay a positive price—

Fortunately for the market system, most goods are private goods. Food, clothing, shelter, and most other desirable things in life are excludable and rival in consumption, so markets can provide us with most things. Yet there are crucial goods that don’t meet these criteria—

Public Goods

A public good is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption.

A public good is the exact opposite of a private good: it is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. A public sewage system is an example of a public good: you can’t keep a river clean without making it clean for everyone who lives near its banks, and my protection from sewage contamination does not prevent my neighbor from being protected as well.

Here are some other examples of public goods:

- Disease prevention. When a disease is stamped out, no one can be excluded from the benefit, and one person’s health doesn’t prevent others from being healthy.

- National defense. A strong military protects all citizens.

- Scientific research. In many cases new findings provide widespread benefits that are not excludable or rival.

Because these goods are nonexcludable, they suffer from the free-

Providing Public Goods

Public goods are provided in a variety of ways. The government doesn’t always get involved—

Some public goods are supplied through voluntary contributions. For example, private donations help support public radio and a considerable amount of scientific research. But private donations are insufficient to finance large programs of great importance, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and national defense.

Some public goods are supplied by self-

Some potentially public goods are deliberately made excludable and therefore subject to charge, like pay-

In small communities, a high level of social encouragement or pressure can be brought to bear on people to contribute money or time to provide the efficient level of a public good. Volunteer fire departments, which depend both on the volunteered services of the firefighters themselves and on contributions from local residents, are a good example. But as communities grow larger and more anonymous, social pressure is increasingly difficult to apply, compelling larger towns and cities to tax residents and depend on salaried firefighters for fire protection services.

As this last example suggests, when other solutions fail, it is up to the government to provide public goods. Indeed, the most important public goods—

How Much of a Public Good Should Be Provided?

In some cases, the provision of a public good is an “either–

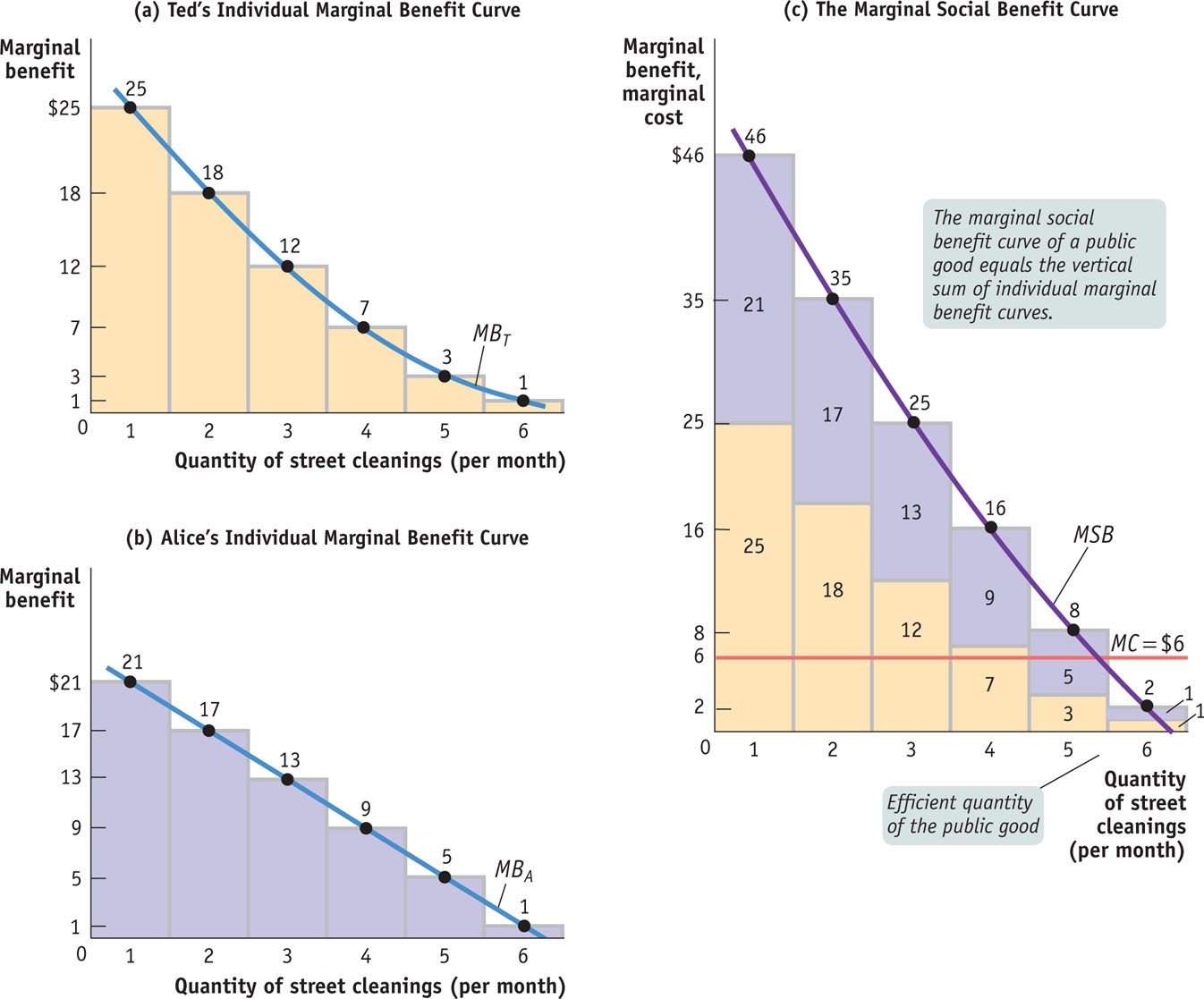

Imagine a city with only two residents, Ted and Alice. Assume that the public good in question is street cleaning and that Ted and Alice truthfully tell the government how much they value a unit of the public good, one unit being one street cleaning per month. Specifically, each of them tells the government his or her willingness to pay for another unit of the public good supplied—

Using this information along with information on the cost of providing the good, the government can use marginal analysis to find the efficient level of providing the public good: the level at which the marginal social benefit of the public good is equal to the marginal social cost of producing it. Recall that the marginal social benefit of a good is the benefit that accrues to society as a whole from the consumption of one additional unit of the good.

But what is the marginal social benefit of another unit of a public good—

This question leads us to an important principle: In the special case of a public good, the marginal social benefit of a unit of the good is equal to the sum of the individual marginal benefits enjoyed by all consumers of that unit. Or to consider it from a slightly different angle, if a consumer could be compelled to pay for a unit before consuming it (the good is made excludable), then the marginal social benefit of a unit is equal to the sum of each consumer’s willingness to pay for that unit. Using this principle, the marginal social benefit of an additional street cleaning per month is equal to Ted’s individual marginal benefit from that additional cleaning plus Alice’s individual marginal benefit.

Why? Because a public good is nonrival in consumption—

Figure 38-2 illustrates the efficient provision of a public good, showing three marginal benefit curves. Panel (a) shows Ted’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBT: he would be willing to pay $25 for the city to clean its streets once a month, an additional $18 to have it done a second time, and so on. Panel (b) shows Alice’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBA. Panel (c) shows the marginal social benefit curve from street cleaning, MSB: it is the vertical sum of Ted’s and Alice’s individual marginal benefit curves, MBT and MBA.

FIGURE38-2A Public Good

To maximize society’s welfare, the government should increase the quantity of street cleanings until the marginal social benefit of an additional cleaning would fall below the marginal social cost. Suppose that the marginal social cost is $6 per cleaning. Then the city should clean its streets 5 times per month, because the marginal social benefit of each of the first 5 cleanings is more than $6, but going from 5 to 6 cleanings would yield a marginal social benefit of only $2, which is less than the marginal social cost.

One basic rationale for the existence of government is that it provides a way for citizens to tax themselves in order to provide public goods—

Of course, if society really consisted of only two individuals, they would probably manage to strike a deal to provide the good. But imagine a city with a million residents, each of whose marginal benefit from a good is only a tiny fraction of the marginal social benefit. It would be impossible for people to reach a voluntary agreement to pay for the efficient level of a good like street cleaning—

VOTING AS A PUBLIC GOOD

It’s a sad fact that many Americans who are eligible to vote don’t bother to. As a result, their interests tend to be ignored by politicians. But what’s even sadder is that this self-

As the economist Mancur Olson pointed out in a famous book titled The Logic of Collective Action, voting is a public good, one that suffers from severe free-

Imagine that you are one of a million people who would stand to gain the equivalent of $100 each if some plan is passed in a statewide referendum—

If you are rational, the answer is no! The reason is that it is very unlikely that your vote will decide the issue, either way. If the measure passes, you benefit, even if you didn’t bother to vote—

Of course, many people do vote out of a sense of civic duty. But because political action is a public good, in general people devote too little effort to defending their own interests.

The result, Olson pointed out, is that when a large group of people share a common political interest, they are likely to exert too little effort promoting their cause and so will be ignored. Conversely, small, well-

Is this a reason to distrust democracy? Winston Churchill said it best: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the other forms that have been tried.”

Common Resources

A common resource is nonexcludable and rival in consumption: you can’t stop me from consuming the good, and more consumption by me means less of the good available for you.

A common resource is a good that is nonexcludable but is rival in consumption. An example is the stock of fish in a fishing area, like the fisheries off the coast of New England. Traditionally, anyone who had a boat could go out to sea and catch fish—

Other examples of common resources include clean air, water, and the diversity of animal and plant species on the planet (biodiversity). In each of these cases the fact that the good is rival in consumption, and yet nonexcludable, poses a serious problem.

The Problem of Overuse

Overuse is the depletion of a common resource that occurs when individuals ignore the fact that their use depletes the amount of the resource remaining for others.

Because common resources are nonexcludable, individuals cannot be charged for their use. But the resources are rival in consumption, so an individual who uses a unit depletes the resource by making that unit unavailable to others. As a result, a common resource is subject to overuse: an individual will continue to use it until his or her marginal benefit is equal to his or her individual marginal cost, ignoring the cost that this action inflicts on society as a whole.

Fish are a classic example of a common resource. Particularly in heavily fished waters, my fishing imposes a cost on others by reducing the fish population and making it harder for others to catch fish. But I have no personal incentive to take this cost into account, since I cannot be charged for fishing. As a result, from society’s point of view, I catch too many fish.

Traffic congestion is another example of overuse of a common resource. A major highway during rush hour can accommodate only a certain number of vehicles per hour. If I decide to drive to work alone rather than carpool or work at home, I cause many other people to have a longer commute; but I have no incentive to take these consequences into account.

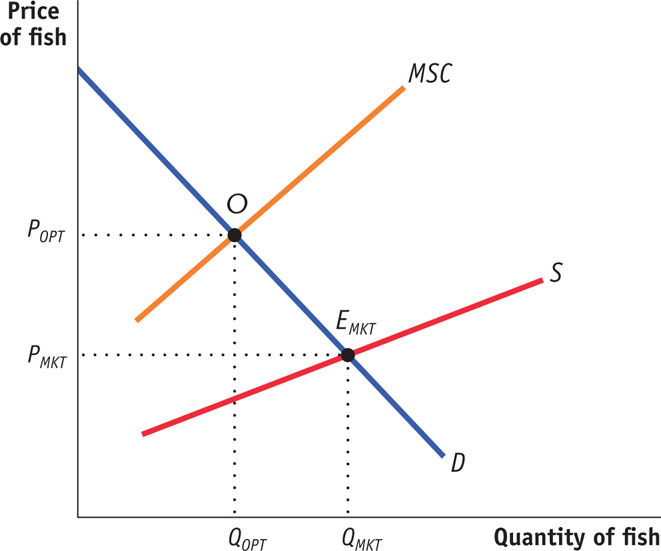

In the case of a common resource, the marginal social cost of my use of that resource is higher than my individual marginal cost, the cost to me of using an additional unit of the good. Figure 38-3 illustrates this point. It shows the demand curve for fish, which measures the marginal benefit of fish (as well as the marginal social benefit because there are no external benefits from catching and consuming fish).

FIGURE38-3A Common Resource

The figure also shows the supply curve for fish, which measures the marginal cost of production of the fishing industry. We know that the industry supply curve is the horizontal sum of each individual fisherman’s supply curve—

As we noted, there is a close parallel between the problem of managing a common resource and the problem posed by negative externalities. In the case of an activity that generates a negative externality, the marginal social cost of production is greater than the marginal cost of production, the difference being the marginal external cost imposed on society. Here, the loss to society arising from a fisher’s depletion of the common resource plays the same role as the external cost when there is a negative externality. In fact, many negative externalities (such as pollution) can be thought of as involving common resources (such as clean air).

The Efficient Use and Maintenance of a Common Resource

Because common resources pose problems similar to those created by negative externalities, the solutions are also similar. To ensure efficient use of a common resource, society must find a way to get individual users of the resource to take into account the costs they impose on others. This is the same principle as that of getting individuals to internalize a negative externality that arises from their actions.

There are three principal ways to induce people who use common resources to internalize the costs they impose on others:

- Tax or otherwise regulate the use of the common resource

- Create a system of tradable licenses for the right to use the common resource

- Make the common resource excludable and assign property rights to some individuals

Tax and RegulateLike activities that generate negative externalities, use of a common resource can be reduced to the efficient quantity by imposing a Pigouvian tax. For example, some countries have imposed “congestion charges” on those who drive during rush hour, in effect charging them for the use of highway space, a common resource. Likewise, visitors to national parks in the United States must pay an entry fee that is essentially a Pigouvian tax.

Create a System of Tradable LicensesAnother way to correct the problem of overuse is to create a system of tradable licenses for the use of the common resource, much like the systems designed to address negative externalities. The policy maker issues the number of licenses that corresponds to the efficient level of use of the good. Making the licenses tradable ensures that the right to use the good is allocated efficiently—

Assign Property RightsBut when it comes to common resources, often the most natural solution is simply to assign property rights. At a fundamental level, common resources are subject to overuse because nobody owns them. The essence of ownership of a good—

When a good is nonexcludable, in a very real sense no one owns it because a property right cannot be enforced—

Artificially Scarce Goods

An artificially scarce good is a good that is excludable but nonrival in consumption.

An artificially scarce good is a good that is excludable but nonrival in consumption. As we’ve already seen, pay-

Markets will supply artificially scarce goods because their excludability allows firms to charge people for them. However, since the efficient price is equal to the marginal cost of zero and the actual price is something higher than that, the good is “artificially scarce” and consumption is inefficiently low. The problem is that, unless the producer can somehow earn revenue from producing and selling the good, none will be produced, which is likely to be worse than a positive but inefficiently low quantity.

We have seen that, in the cases of public goods, common resources, and artificially scarce goods, a market economy will not provide adequate incentives for efficient levels of production and consumption. Fortunately for the sake of market efficiency, most goods are private goods. Food, clothing, shelter, and most other desirable things in life are excludable and rival in consumption, so the types of market failure discussed in this module are important exceptions rather than the norm.

38

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. For each of the following goods, indicate whether it is excludable, whether it is rival in consumption, and what kind of good it is.

-

a. a public space such as a park

A public space is generally nonexcludable, but it may or may not be rival in consumption, depending on the level of congestion. For example, if you and I are the only users of a jogging path in the public park, then your use will not prevent my use—the path is non rival in consumption. In this case the public space is a public good. But the space is rival in consumption if there are many people trying to use the jogging path at the same time or if my use of the public tennis court prevents your use of the same court. In this case the public space becomes a common resource. -

b. a cheese burrito

A cheese burrito is both excludable and rival in consumption. Hence it is a private good. -

c. information from a website that is password-

protected Information from a password-protected web site is excludable but non rival in consumption. So it is an artificially scarce good. -

d. publicly announced information about the path of an incoming hurricane

Publicly announced information about the path of an incoming hurricane is nonexcludable and non rival in consumption, so it is a public good.

2. Which of the goods in Question 1 will be provided by a private producer without government intervention? Which will not be? Explain your answer.

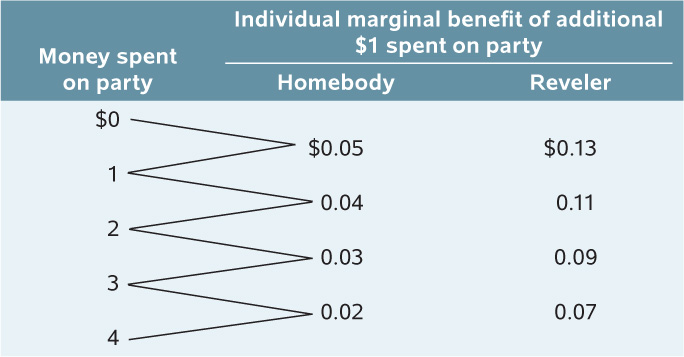

3. The town of Centreville, population 16, has two types of residents, Homebodies and Revelers. Using the accompanying table, the town must decide how much to spend on its New Year’s Eve party. No individual resident expects to directly bear the cost of the party.

-

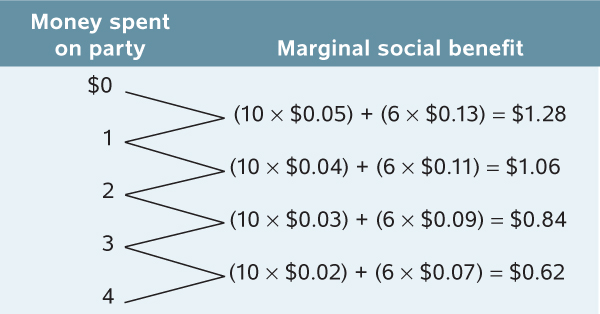

a. Suppose there are 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers. Determine the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party. What is the efficient level of spending?

With 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers, the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party is as shown in the accompanying table.

The efficient spending level is $2, the highest level for which the marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1). -

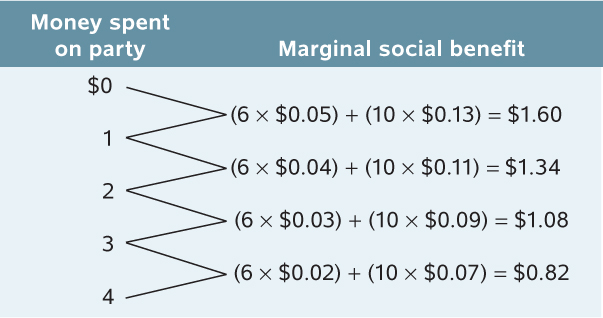

b. Suppose there are 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers. How do your answers to part a change? Explain.

With 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers, the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party is as shown in the accompanying table. c

c

The efficient spending level is now $3, the highest level for which the marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1). The efficient level of spending has increased from that in part a because with relatively more Revelers than Homebodies, an additional dollar spent on the party generates a higher level of social benefit compared to when there are relatively more Homebodies than Revelers. -

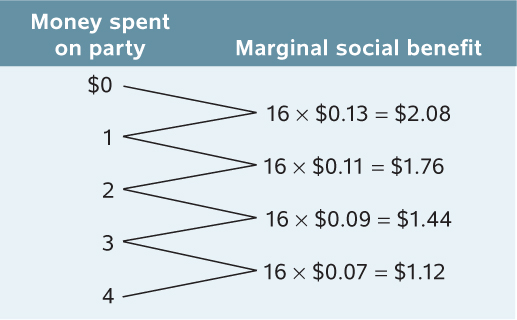

c. Suppose that the individual marginal benefit schedules are known but no one knows the true proportion of Homebodies versus Revelers. Individuals are asked their preferences. What is the likely outcome if each person assumes that others will pay for any additional amount of the public good? Why is it likely to result in an inefficiently high level of spending? Explain.

When the numbers of Homebodies and Revelers are unknown but residents are asked their preferences, Homebodies will pretend to be Revelers to induce a higher level of spending on the public party. That’s because a Homebody still receives a positive individual marginal benefit from an additional $1 spent, despite the fact that his or her individual marginal benefit is lower than that of a Reveler for every additional $1. In this case the “reported” marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party will be as shown in the accompanying table.

As a result, $4 will be spent on the party, the highest level for which the “reported” marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1). Regardless of whether there are 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers (part a) or 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers (part b), spending $4 in total on the party is clearly inefficient because marginal cost exceeds marginal social benefit at this spending level.

4. Rocky Mountain Forest is a government-

5. You are the new Forest Service Commissioner and have been instructed to come up with ways to preserve the Rocky Mountain Forest for the general public. Name three different methods you could use to maintain the efficient level of tree harvesting and explain how each would work. For each method, what information would you need to know in order to achieve an efficient outcome?

- i. Pigouvian taxes. You would enforce a tax on loggers that equals the difference between the marginal social cost and the individual marginal cost of logging a tree at the socially efficient harvest amount. In order to do this, you must know the marginal social cost schedule and the individual marginal cost schedule.

- ii. System of tradable licenses. You would issue tradable licenses, setting the total number of trees harvested equal to the socially efficient harvest number. The market that arises in these licenses will allocate the right to log efficiently when loggers differ in their costs of logging: licenses will be purchased by those who have a relatively lower cost of logging. The market price of a license will be equal to the difference between the marginal social cost and the individual marginal cost of logging a tree at the socially efficient harvest amount. In order to implement this level, you need to know the socially efficient harvest amount.

- iii. Allocation of property rights. Here you would sell or give the forest to a private party. This party will have the right to exclude others from harvesting trees. Harvesting is now a private good—it is excludable and rival in consumption. As a result, there is no longer any divergence between social and private costs, and the private party will harvest the efficient level of trees. You need no additional information to use this method.

Multiple-

Question

1. Which of the following types of goods are always nonrival in consumption?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. The free-

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Public goods are sometimes provided through which of the following means?

I. voluntary contributions

II. individual self-

III. the government

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

4. Market provision of a public good will lead to

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. The overuse of a common resource can be reduced by which of the following?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

1. Identify and explain the two characteristics shared by every public good.

2. Suppose a new resident moves to a community that purchases a public good for the benefit of every member of the community. What is the additional cost of providing the public good to the new community member? Explain.

THE MARGINAL COST OF WHAT EXACTLY?

When we consider the marginal cost of a good that is nonrival in consumption, what exactly are we thinking about? What about a good that is rival in consumption?

When we consider the marginal cost of a good that is nonrival in consumption, what exactly are we thinking about? What about a good that is rival in consumption?

In the case of a good that is nonrival in consumption, we could consider either the marginal cost of producing a unit of the good or the marginal cost of allowing a unit of the good to be consumed. It is easy to confuse the two, but try not to. To help clarify the distinction, consider this example: the satellite TV provider DirecTV incurs a marginal cost in making a movie available to its subscribers that is equal to the cost of the resources it uses to produce and broadcast that movie. However, once that movie is being broadcast, no marginal cost is incurred by letting an additional family watch it. In other words, no costly resources are “used up” when one more family consumes a movie that has already been produced and is being broadcast.

In the case of a good that is nonrival in consumption, we could consider either the marginal cost of producing a unit of the good or the marginal cost of allowing a unit of the good to be consumed. It is easy to confuse the two, but try not to. To help clarify the distinction, consider this example: the satellite TV provider DirecTV incurs a marginal cost in making a movie available to its subscribers that is equal to the cost of the resources it uses to produce and broadcast that movie. However, once that movie is being broadcast, no marginal cost is incurred by letting an additional family watch it. In other words, no costly resources are “used up” when one more family consumes a movie that has already been produced and is being broadcast.

This complication does not arise, however, when a good is rival in consumption. In this case, the resources used to produce a unit of the good are “used up” by a person’s consumption of it—