1.2 12Efficiency and Markets

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The meaning and importance of total surplus and how it can be used to illustrate efficiency in markets

The meaning and importance of total surplus and how it can be used to illustrate efficiency in markets

Why property rights and prices as economic signals are critical to the smooth functioning of a market

Why property rights and prices as economic signals are critical to the smooth functioning of a market

Why markets typically lead to efficient outcomes despite the fact that they sometimes fail

Why markets typically lead to efficient outcomes despite the fact that they sometimes fail

Consumer Surplus, Producer Surplus, and Efficiency

Markets are a remarkably effective way to organize economic activity: under the right conditions, they can make society as well off as possible given the available resources. The concepts of consumer and producer surplus introduced in the previous module can help us deepen our understanding of why this is so.

The Gains from Trade

Let’s return to the market for used textbooks, but now consider a much bigger market—

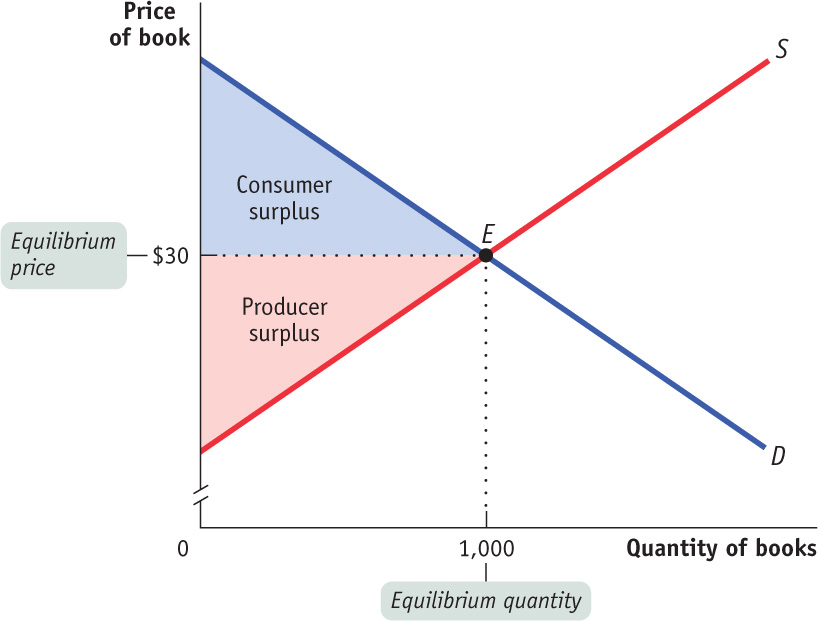

FIGURE12-1Total Surplus

Similarly, we can line up outgoing students, who are potential sellers of the book, in order of their cost, starting with the student with the lowest cost, then the student with the next lowest cost, and so on, to derive a supply curve like the one shown in the same figure.

Total surplus is the total net gain to consumers and producers from trading in a market. It is the sum of producer and consumer surplus.

As we have drawn the curves, the market reaches equilibrium at a price of $30 per book, and 1,000 books are bought and sold at that price. The two shaded triangles show the consumer surplus (blue) and the producer surplus (red) generated by this market. The sum of consumer and producer surplus is known as total surplus.

The striking thing about this picture is that both consumers and producers gain—

But are we as well off as we could be? This brings us to the question of the efficiency of markets.

The Efficiency of Markets

A market is efficient if, once the market has produced its gains from trade, there is no way to make some people better off without making other people worse off. Note that market equilibrium is just one way of deciding who consumes a good and who sells a good. To better understand how markets promote efficiency, let’s examine some alternatives.

Consider the example of kidney transplants discussed earlier in the Economics in Action in Module 11. There is not a market for kidneys, and available kidneys currently go to whoever has been on the waiting list the longest. Of course, those who have been waiting the longest aren’t necessarily those who would benefit the most from a new kidney.

Similarly, imagine a committee charged with improving on the market equilibrium by deciding who gets and who gives up a used textbook. The committee’s ultimate goal would be to bypass the market outcome and come up with another arrangement that would increase total surplus.

Let’s consider three approaches the committee could take:

- It could reallocate consumption among consumers.

- It could reallocate sales among sellers.

- It could change the quantity traded.

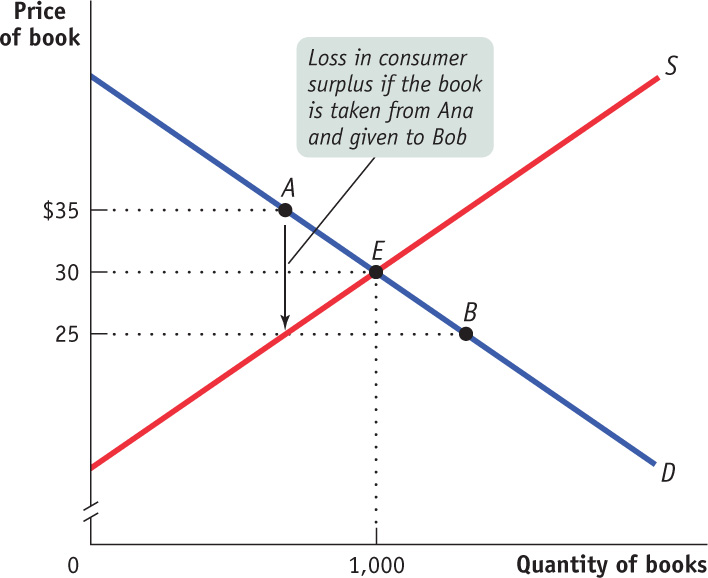

Reallocate Consumption Among ConsumersThe committee might try to increase total surplus by selling books to different consumers. Figure 12-2 shows why this will result in lower surplus compared to the market equilibrium outcome. Points A and B show the positions on the demand curve of two potential buyers of used books, Ana and Bob. As we can see from the figure, Ana is willing to pay $35 for a book, but Bob is willing to pay only $25. Since the market equilibrium price is $30, under the market outcome Ana gets a book and Bob does not.

FIGURE12-2Reallocating Consumption Lowers Consumer Surplus

Now suppose the committee reallocates consumption. This would mean taking the book away from Ana and giving it to Bob. Since the book is worth $35 to Ana but only $25 to Bob, this change reduces total consumer surplus by $35 − $25 = $10. Moreover, this result doesn’t depend on which two students we pick. Every student who buys a book at the market equilibrium price has a willingness to pay of $30 or more, and every student who doesn’t buy a book has a willingness to pay of less than $30. So reallocating the good among consumers always means taking a book away from a student who values it more and giving it to one who values it less. This necessarily reduces total consumer surplus.

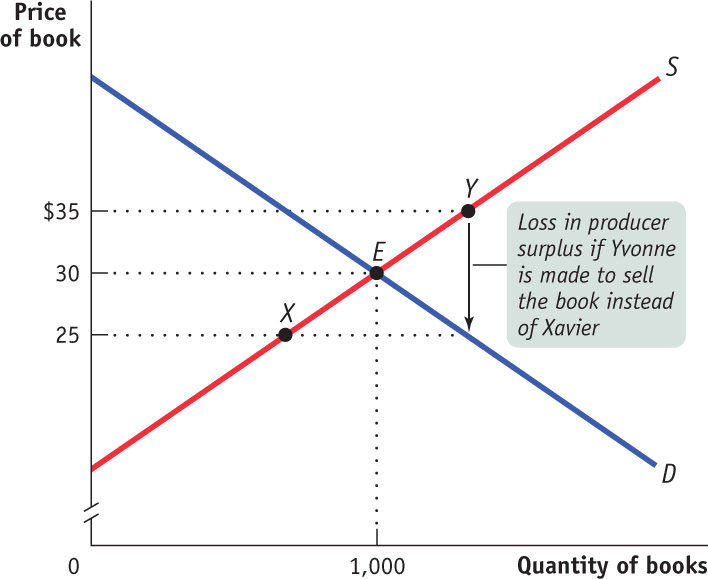

Reallocate Sales Among SellersThe committee might try to increase total surplus by altering who sells their books, taking sales away from sellers who would have sold their books in the market equilibrium and instead compelling those who would not have sold their books in the market equilibrium to sell them.

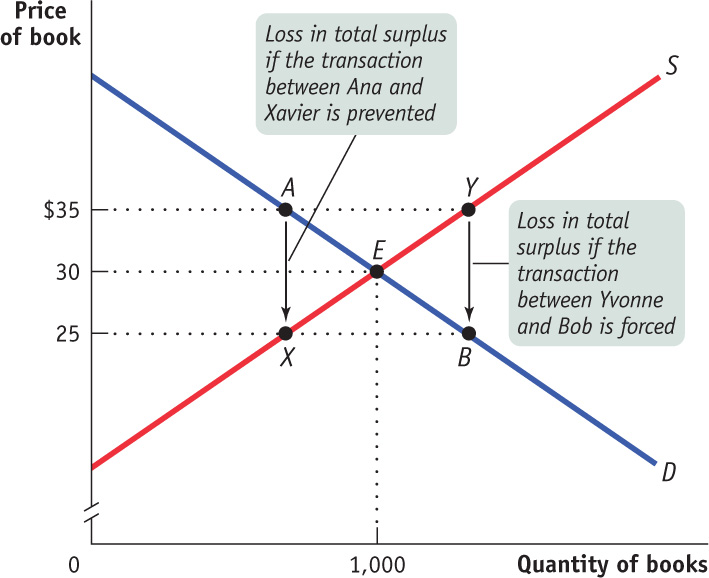

Figure 12-3 shows why this will result in lower surplus. Here points X and Y show the positions on the supply curve of Xavier, who has a cost of $25, and Yvonne, who has a cost of $35. At the equilibrium market price of $30, Xavier would sell his book but Yvonne would not sell hers. If the committee reallocated sales, forcing Xavier to keep his book and Yvonne to sell hers, total producer surplus would be reduced by $35 − $25 = $10.

FIGURE12-3Reallocating Sales Lowers Producer Surplus

Again, it doesn’t matter which two students we choose. Any student who sells a book at the market equilibrium price has a lower cost than any student who keeps a book. So reallocating sales among sellers necessarily increases total cost and reduces total producer surplus.

Change the Quantity TradedThe committee might try to increase total surplus by compelling students to trade either more books or fewer books than the market equilibrium quantity.

Figure 12-4 shows why this will result in lower surplus. It shows all four students: potential buyers Ana and Bob, and potential sellers Xavier and Yvonne. To reduce sales, the committee will have to prevent a transaction that would have occurred in the market equilibrium—

FIGURE12-4Changing the Quantity Lowers Total Surplus

Once again, this result doesn’t depend on which two students we pick: any student who would have sold the book in the market equilibrium has a cost of $30 or less, and any student who would have purchased the book in the market equilibrium has a willingness to pay of $30 or more. So preventing any sale that would have occurred in the market equilibrium necessarily reduces total surplus.

Finally, the committee might try to increase sales by forcing Yvonne, who would not have sold her book in the market equilibrium, to sell it to someone like Bob, who would not have bought a book in the market equilibrium. Because Yvonne’s cost is $35, but Bob is only willing to pay $25, this transaction reduces total surplus by $10. And once again it doesn’t matter which two students we pick—

The key point to remember is that once this market is in equilibrium, there is no way to increase the gains from trade. Any other outcome reduces total surplus. We can summarize our results by stating that an efficient market performs four important functions:

- It allocates consumption of the good to the potential buyers who most value it, as indicated by the fact that they have the highest willingness to pay.

- It allocates sales to the potential sellers who most value the right to sell the good, as indicated by the fact that they have the lowest cost.

- It ensures that every consumer who makes a purchase values the good more than every seller who makes a sale, so that all transactions are mutually beneficial.

- It ensures that every potential buyer who doesn’t make a purchase values the good less than every potential seller who doesn’t make a sale, so that no mutually beneficial transactions are missed.

As a result of these four functions, any way of allocating the good other than the market equilibrium outcome will lower total surplus.

There are three caveats, however. First, although a market may be efficient, it isn’t necessarily fair. In fact, fairness, or equity, is often in conflict with efficiency. We’ll discuss this next.

The second caveat is that markets sometimes fail. Under some well-

Third, even when the market equilibrium maximizes total surplus, this does not mean that it results in the best outcome for every individual consumer and producer. Other things equal, each buyer would like to pay a lower price and each seller would like to receive a higher price. So if the government were to intervene in the market—

Equity and Efficiency

It’s easy to get carried away with the idea that markets are always good and that economic policies that interfere with efficiency are bad. But that would be misguided because there is another factor to consider: society cares about equity, or what’s “fair.”

There is often a trade-

Consider, for example, patients who need kidney transplants. For them, the guidelines proposed by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), covered earlier, will be unwelcome news. Those who have waited years for a transplant will no doubt find the guidelines, which give precedence to younger patients,…well…unfair. And the guidelines raise other questions about fairness: Why limit potential transplant recipients to only Americans? Why not give precedence to those who have made recognized contributions to society? And so on.

The point is that efficiency is about how to achieve goals, not what those goals should be. For example, UNOS decided that its goal is to maximize the life span of kidney recipients. Some might have argued for a different goal, and efficiency does not address which goal is the best. What efficiency does address is the best way to achieve a goal once it has been determined.

It’s important to understand that fairness, unlike efficiency, can be very hard to define. Fairness is a concept about which well-

A Market Economy

As we learned earlier, in a market economy decisions about production and consumption are made via markets. In fact, the economy as a whole is made up of many interrelated markets. Up until now, to learn how markets work, we’ve been examining a single market—

We know that an efficient market equilibrium maximizes total surplus—

When each and every market in the economy maximizes total surplus, then the economy as a whole is efficient. This is a very important result: just as it is impossible to make someone better off without making other people worse off in a single market when it is efficient, the same is true when each and every market in that economy is efficient. However, it is virtually impossible to find an economy in which every market is efficient.

For now, let’s examine why markets and market economies typically work so well. Once we understand why, we can then briefly address why markets sometimes get it wrong.

Why Markets Typically Work So Well

Economists have written volumes about why markets are an effective way to organize an economy. In the end, well-

Property rights are the rights of owners of valuable items, whether resources or goods, to dispose of those items as they choose.

Property rights are a system in which valuable items in the economy have specific owners who can dispose of them as they choose. In a system of property rights, by purchasing a good you receive “ownership rights”: the right to use and dispose of the good as you see fit. Property rights are what make the mutually beneficial transactions in the used-

To see why property rights are crucial, imagine that students do not have full property rights in their textbooks and are prohibited from reselling them when the semester ends. This restriction on property rights would prevent many mutually beneficial transactions. Some students would be stuck with textbooks they will never reread when they would be much happier receiving some cash instead. Other students would be forced to pay full price for brand-

An economic signal is any piece of information that helps people make better economic decisions.

Once a system of well-

But prices are far and away the most important signals in a market economy, because they convey essential information about other people’s costs and their willingness to pay. If the equilibrium price of used books is $30, this in effect tells everyone both that there are consumers willing to pay $30 and up and that there are potential sellers with a cost of $30 or less. The signal given by the market price ensures that total surplus is maximized by telling people whether to buy books, sell books, or do nothing at all.

This example shows that the market price “signals” to consumers with a willingness to pay equal to or more than the market price that they should buy the good, just as it signals to producers with a cost equal to or less than the market price that they should sell the good. And since, in equilibrium, the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied, all willing consumers will find willing sellers.

Prices can sometimes fail as economic signals. Sometimes a price is not an accurate indicator of how desirable a good is. For example, you can’t infer from the price alone whether a used car is good or a “lemon.”

Why Markets Can Sometimes Get It Wrong

A market or an economy is inefficient if there are missed opportunities: some people could be made better off without making other people worse off.

Although markets are an amazingly effective way to organize economic activity, as we’ve noted, markets can sometimes get it wrong—

Market failure occurs when a market fails to be efficient.

Markets can be inefficient for a number of reasons. Two of the most important are a lack of property rights and inaccuracy of prices as economic signals. When a market is inefficient, we have what is known as market failure. We will examine various types of market failure in later modules. For now, let’s review the three main ways in which markets sometimes fall short of efficiency.

- Markets can fail when, in an attempt to capture more surplus, one party prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring. This situation arises, for instance, when a market contains only a single seller of a good, known as a monopolist. A monopolist creates inefficiency by manipulating the market price to increase profits.

- Actions of individuals sometimes have side effects on the welfare of others that markets don’t take into account. In economics, these side effects are known as externalities, and the best-

known example is pollution. We can think of pollution as a problem of incomplete property rights; for example, existing property rights don’t guarantee a right to ownership of clean air. Pollution and other externalities also give rise to inefficiency. - Markets for some goods fail because these goods, by their very nature, are unsuited for efficient management by markets. Falling into this category are goods for which some people possess information that others don’t have. For example, the seller of a used car that is a “lemon” may have information that is unknown to potential buyers. Also in this category are goods for which there are problems limiting people’s access to and consumption of the good; examples are fish in the sea and trees in the Amazonian rain forest. In these instances, markets generally fail due to incomplete property rights.

But even with these limitations, it’s remarkable how well markets work at maximizing the gains from trade.

12

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. Using the tables in Check Your Understanding in the preceding module, find the equilibrium price and quantity in the market for cheese-

2. Using your answers from the previous question, show how each of the following three actions reduces total surplus:

-

a. Having Josey consume one fewer pepper, and Casey one more pepper, than in the market equilibrium

If Josey consumes one fewer pepper, she loses $0.10 (her consumer surplus on the second pepper when market price is $0.50); if Casey consumes one more pepper, he loses $0.20 (his willingness to pay for his fourth pepper is only $0.30 but the market price is $0.50). This results in an overall loss of consumer surplus of $0.10 + $0.20 = $0.30. -

b. Having Cara produce one fewer pepper, and Jamie one more pepper, than in the market equilibrium

Cara’s producer surplus on the last pepper she supplied (the third pepper) at a market price of $0.50 is $0.10, and Jamie’s loss in terms of producer surplus of producing one more (his third pepper, which costs $0.70 to produce) is $0.20 at a market price of $0.50. Total producer surplus therefore falls by $0.10 + $0.20 = $0.30. -

c. Having Josey consume one fewer pepper, and Cara produce one fewer pepper, than in the market equilibrium

Josey’s consumer surplus from her second pepper is $0.10; this is what she would lose if she were to consume one fewer pepper. Cara’s producer surplus from producing her third pepper is $0.10; this is what she would forego if she were to produce one fewer pepper. Therefore, if we reduced quantity by one pepper, we would lose $0.10 + $0.10 = $0.20 of total surplus.

3. Suppose that in the market for used textbooks the equilibrium price is $30 but it is mistakenly announced that the equilibrium price is $300. How does this mistake affect the efficiency of the market?

Multiple-

Question

1. At market equilibrium in a competitive market, which of the following is necessarily true?

I. Consumer surplus is maximized.

II. Producer surplus is maximized.

III. Total surplus is maximized.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. When a competitive market is in equilibrium, total surplus can be increased by

I. reallocating consumption among consumers.

II. reallocating sales among sellers.

III. changing the quantity traded.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Which of the following is true regarding equity and efficiency in competitive markets?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

4. What features are essential to well-

I. A system of property rights

II. Externalities

III. Economic signals

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. Which of the following is an example of the failure of a system of property rights to assign ownership to the appropriate party?

I. The ability of one student to sell a used textbook to another student.

II. The ability of some fishermen to fish as much as they wish in open waters

III. The ability of a car salesman to make a sale to an interested buyer.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

1. Suppose UNOS alters its proposed guidelines for allocating donated kidneys to give preference to patients with young children, no longer relying solely on the concept of “net benefit.” If total surplus in this case is defined as the total life span of kidney recipients, is this new guideline likely to reduce, increase, or leave total surplus unchanged? How might you justify this new guideline?

2. What is wrong with the following statement? “Markets are always the best way to organize economic activity. Any policies that interfere with markets reduce society’s welfare.”