1.1 13Price Controls (Ceilings and Floors)

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The meaning of price controls, one way government intervenes in markets

The meaning of price controls, one way government intervenes in markets

How price controls can create problems and make a market inefficient

How price controls can create problems and make a market inefficient

Why economists are often deeply skeptical of attempts to intervene in markets

Why economists are often deeply skeptical of attempts to intervene in markets

Who benefits and who loses from price controls, and why they are used despite their well-

Who benefits and who loses from price controls, and why they are used despite their well-known problems

Why Governments Control Prices

As you’ve learned, a market moves to equilibrium—

After all, buyers would always like to pay less if they could, and sometimes they can make a strong moral or political case that they should pay lower prices. For example, what if the equilibrium between supply and demand for apartments in a major city leads to rental rates that an average working person can’t afford? In that case, a government might well be under pressure to impose limits on the rents landlords can charge.

Sellers, however, would always like to get more money for what they sell, and sometimes they can make a strong moral or political case that they should receive higher prices. For example, consider the labor market: the price for an hour of a worker’s time is the wage rate. What if the equilibrium between supply and demand for less skilled workers leads to wage rates that yield an income below the poverty level? In that case, a government might well be pressured to require employers to pay a rate no lower than some specified minimum wage.

Price controls are legal restrictions on how high or low a market price may go. They can take two forms: a price ceiling, a maximum price sellers are allowed to charge for a good or service, or a price floor, a minimum price buyers are required to pay for a good or service.

In other words, there is often a strong political demand for governments to intervene in markets. And powerful interests can make a compelling case that a market intervention favoring them is “fair.” When a government intervenes to regulate prices, we say that it imposes price controls. These controls typically take the form of either an upper limit, a price ceiling, or a lower limit, a price floor.

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy to tell a market what to do. As we will now see, when a government tries to legislate prices—

We make an important assumption in this module: the markets in question are efficient before price controls are imposed. Markets can sometimes be inefficient—

Price Ceilings

Aside from rent control, there are not many price ceilings in the United States today. But at times they have been widespread. Price ceilings are typically imposed during crises—

Rent control in New York is a legacy of World War II: it was imposed because wartime production created an economic boom, which increased demand for apartments at a time when the labor and raw materials that might have been used to build them were being used to win the war instead. Although most price controls were removed soon after the war ended, New York’s rent limits were retained and gradually extended to buildings not previously covered, leading to some very strange situations.

You can rent a one-

Aside from producing great deals for some renters, however, what are the broader consequences of New York’s rent-

Modeling a Price Ceiling

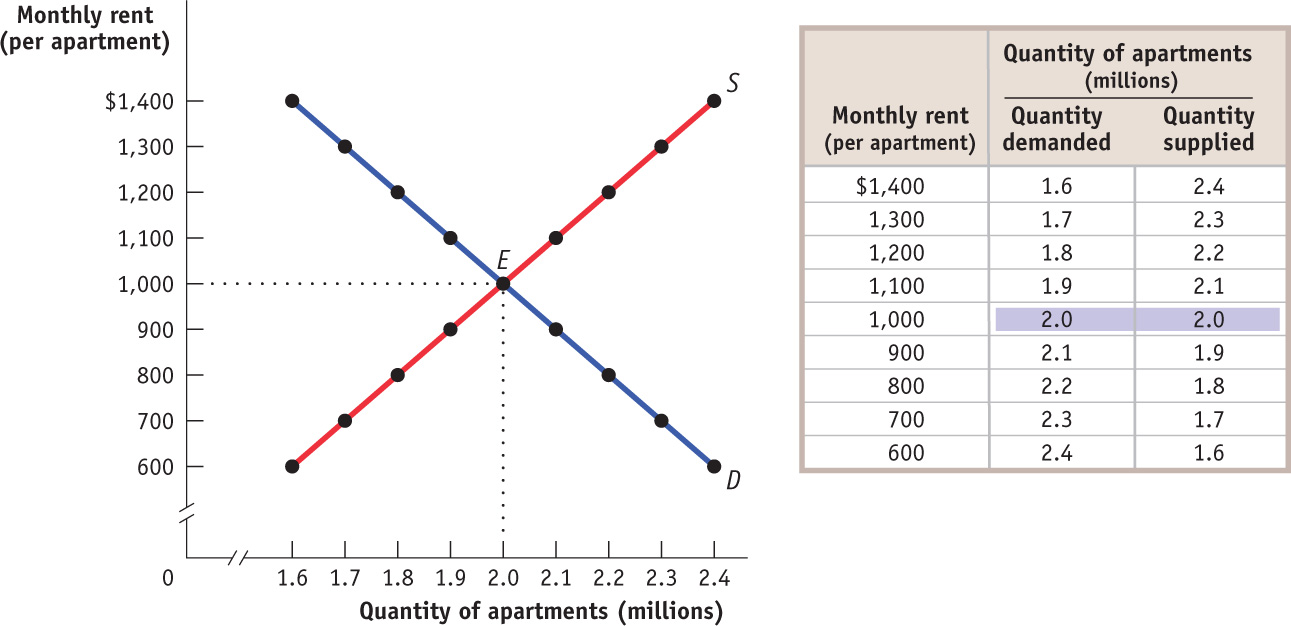

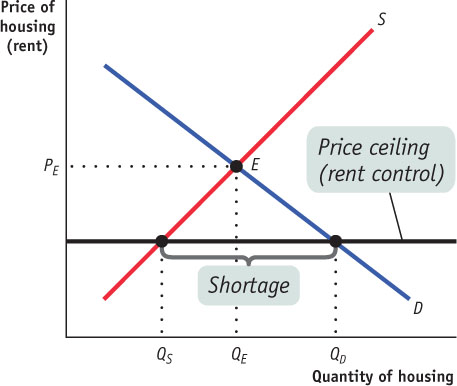

To see what can go wrong when a government imposes a price ceiling on an efficient market, consider Figure 13-1, which shows a simplified model of the market for apartments in New York. For the sake of simplicity, we imagine that all apartments are exactly the same and so would rent for the same price in an unregulated market.

FIGURE13-1The Market for Apartments in the Absence of Government Controls

The table in the figure shows the demand and supply schedules; the demand and supply curves are shown on the left. We show the quantity of apartments on the horizontal axis and the monthly rent per apartment on the vertical axis. You can see that in an unregulated market the equilibrium would be at point E: 2 million apartments would be rented for $1,000 each per month.

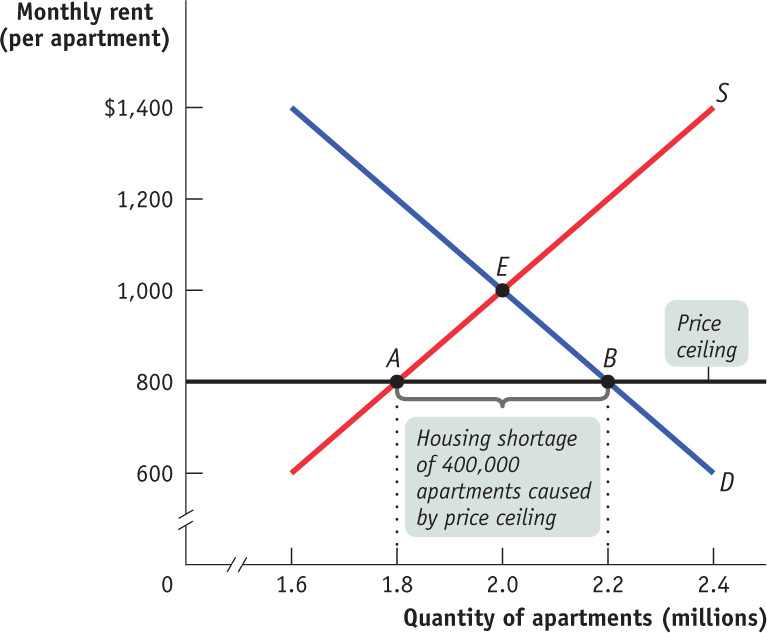

Now suppose that the government imposes a price ceiling, limiting rents to a price below the equilibrium price—

Figure 13-2 shows the effect of the price ceiling, represented by the line at $800. At the enforced rental rate of $800, landlords have less incentive to offer apartments, so they won’t be willing to supply as many as they would at the equilibrium rate of $1,000. They will choose point A on the supply curve, offering only 1.8 million apartments for rent, 200,000 fewer than in the unregulated market. At the same time, more people will want to rent apartments at a price of $800 than at the equilibrium price of $1,000; as shown at point B on the demand curve, at a monthly rent of $800 the quantity of apartments demanded rises to 2.2 million, 200,000 more than in the unregulated market and 400,000 more than are actually available at the price of $800. So there is now a persistent shortage of rental housing: at that price, 400,000 more people want to rent than are able to find apartments.

FIGURE13-2The Effects of a Price Ceiling

Do price ceilings always cause shortages? No. If a price ceiling is set above the equilibrium price, it won’t have any effect. Suppose that the equilibrium rental rate on apartments is $1,000 per month and the city government sets a ceiling of $1,200. Who cares? In this case, the price ceiling won’t be binding—

How a Price Ceiling Causes Inefficiency

The housing shortage shown in Figure 13-2 is not merely annoying: like any shortage induced by price controls, it can be seriously harmful because it leads to inefficiency.

Rent control, like all price ceilings, creates inefficiency in at least three distinct ways. It typically leads to an inefficient allocation of apartments among would-

Inefficient Allocation to ConsumersRent control doesn’t just lead to too few apartments being available. It can also lead to misallocation of the apartments that are available: people who badly need a place to live may not be able to find an apartment, while some apartments may be occupied by people with much less urgent needs.

In the case shown in Figure 13-2, 2.2 million people would like to rent an apartment at $800 per month, but only 1.8 million apartments are available. Of those 2.2 million who are seeking an apartment, some want an apartment badly and are willing to pay a high price to get one. Others have a less urgent need and are only willing to pay a low price, perhaps because they have alternative housing. An efficient allocation of apartments would reflect these differences: people who really want an apartment will get one and people who aren’t all that eager to find an apartment won’t. In an inefficient distribution of apartments, the opposite will happen: some people who are not especially eager to find an apartment will get one and others who are very eager to find an apartment won’t.

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in the form of inefficient allocation to consumers: people who want the good badly and are willing to pay a high price don’t get it, and those who care relatively little about the good and are only willing to pay a relatively low price do get it.

Because people usually get apartments through luck or personal connections under rent control, it generally results in an inefficient allocation to consumers of the few apartments available.

To see the inefficiency involved, consider the Lees, a family with young children who have no alternative housing and would be willing to pay up to $1,500 for an apartment—

This allocation of apartments—

Generally, if people who really want apartments could sublease them from people who are less eager to live there, both those who gain apartments and those who trade their occupancy for money would be better off. However, subletting is illegal under rent control because it would occur at prices above the price ceiling.

The fact that subletting is illegal doesn’t mean it never happens. In fact, chasing down illegal subletting is a major business for New York private investigators, who have been known to use hidden cameras and other tricks to prove that the legal tenants in rent-

Price ceilings typically lead to inefficiency in the form of wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling.

Wasted ResourcesAnother reason a price ceiling causes inefficiency is that it leads to wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling. Back in 1979, U.S. price controls on gasoline led to shortages that forced millions of Americans to spend hours each week waiting in lines at gas stations. The opportunity cost of the time spent in gas lines—

Because of rent control, the Lees will spend all their spare time for several months searching for an apartment, time they would rather have spent working or engaged in family activities. That is, there is an opportunity cost to the Lees’ prolonged search for an apartment—

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in that the goods being offered are of inefficiently low quality: sellers offer low quality goods at a low price even though buyers would prefer a higher quality at a higher price.

Inefficiently Low QualityYet another way a price ceiling causes inefficiency is by causing goods to be of inefficiently low quality. Inefficiently low quality means that sellers offer low-

Again, consider rent control. Landlords have no incentive to provide better conditions because they cannot raise rents to cover their repair costs but are able to find tenants easily. In many cases, tenants would be willing to pay much more for improved conditions than it would cost for the landlord to provide them—

This whole situation is a missed opportunity—

A black market is a market in which goods or services are bought and sold illegally—

Black MarketsAnd that leads us to a last aspect of price ceilings: the incentive they provide for illegal activities, specifically the emergence of black markets. We have already described one kind of black market activity—

What’s wrong with black markets? In general, it’s a bad thing if people break any law, because it encourages disrespect for the law in general. Worse yet, in this case illegal activity worsens the position of those who try to be honest. If the Lees are scrupulous about upholding the rent-

So Why Are There Price Ceilings?

We have seen three common results of price ceilings:

- a persistent shortage of the good

- inefficiency arising from this persistent shortage in the form of inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of the good to consumers, resources wasted in searching for the good, and the inefficiently low quality of the good offered for sale

- the emergence of illegal, black market activity

Given the unpleasant consequences of price ceilings, why do governments sometimes impose them?

One answer is that although price ceilings may have adverse effects, they do benefit some people. In practice, New York’s rent-

Also, when price ceilings have been in effect for a long time, buyers may not have a realistic idea of what would happen without them. In our previous example, the rental rate in an unregulated market (Figure 13-1) would be only 25% higher than in the regulated market (Figure 13-2): $1,000 instead of $800. But how would renters know that? Indeed, they might have heard about black market transactions at much higher prices—

A last answer is that government officials often do not understand supply and demand analysis! It is a great mistake to suppose that economic policies in the real world are always sensible or well informed.

HUNGER AND PRICE CONTROLS IN VENEZUELA

Something was rotten in the state of Venezuela—

Generous government policies led to higher spending by consumers and sharply rising prices for goods that weren’t subject to price controls or were bought on the black market. The result was a big increase in the demand for price-

As the shortages persisted and inflation of food prices worsened (in the first five months of 2010, the prices of food and drink rose by 21%), Chávez declared “economic war” on the private sector, berating it for “hoarding and smuggling.” The government expropriated farms, food manufacturers, and grocery stores, creating in their place government-

Not surprisingly, the shelves were far more bare in government-

Price Floors

The minimum wage is a legal floor on the wage rate, which is the market price of labor.

Sometimes governments intervene to push market prices up instead of down. Price floors have been widely legislated for agricultural products, such as wheat and milk, as a way to support the incomes of farmers. Historically, there were also price floors on such services as trucking and air travel, although these were phased out by the U.S. government in the 1970s. If you have ever worked in a fast-

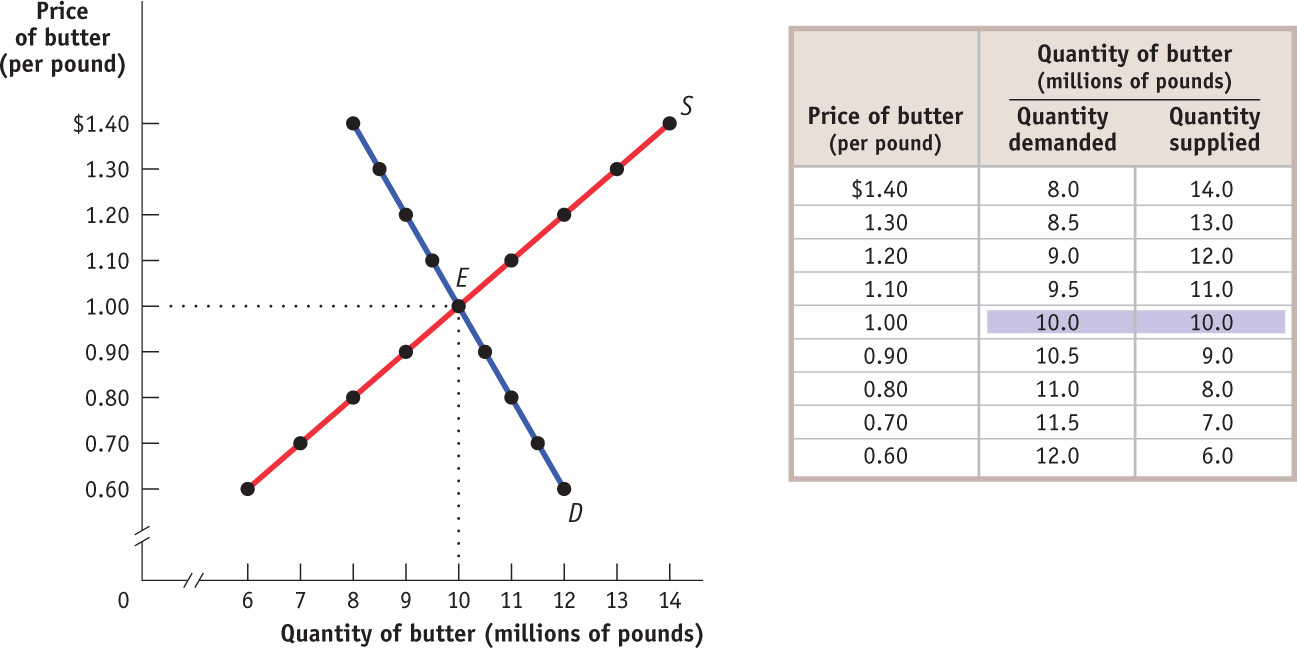

Just like price ceilings, price floors are intended to help some people but generate predictable and undesirable side effects. Figure 13-3 shows hypothetical supply and demand curves for butter. Left to itself, the market would move to equilibrium at point E, with 10 million pounds of butter bought and sold at a price of $1 per pound.

FIGURE13-3The Market for Butter in the Absence of Government Controls

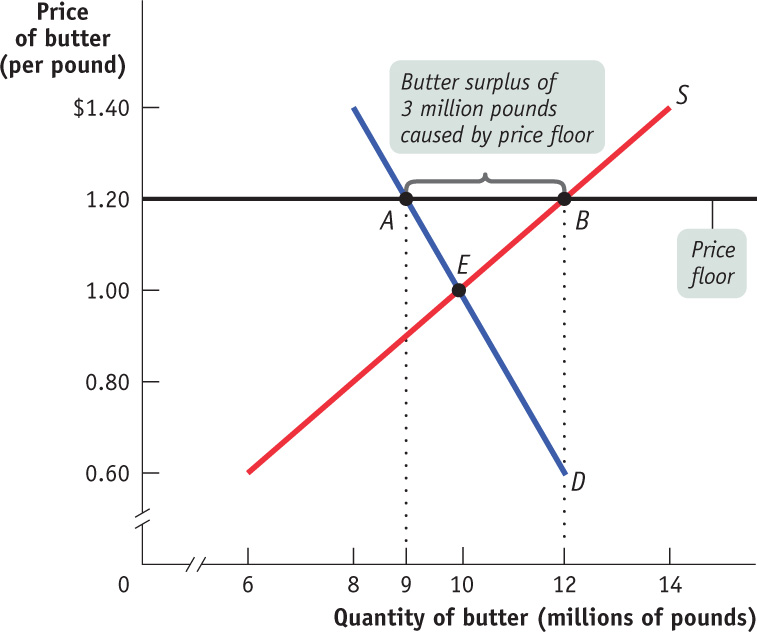

Now suppose that the government, in order to help dairy farmers, imposes a price floor on butter of $1.20 per pound. Its effects are shown in Figure 13-4, where the line at $1.20 represents the price floor. At a price of $1.20 per pound, producers would want to supply 12 million pounds (point B on the supply curve) but consumers would want to buy only 9 million pounds (point A on the demand curve). So the price floor leads to a persistent surplus of 3 million pounds of butter.

FIGURE13-4The Effects of a Price Floor

PRICE FLOORS AND SCHOOL LUNCHES

When you were in grade school, did your school offer free or very cheap lunches? If so, you were probably a beneficiary of price floors.

Where did all the cheap food come from? During the 1930s, when the U.S. economy was going through the Great Depression, a prolonged economic slump, prices were low and farmers were suffering severely. In an effort to help rural Americans, the U.S. government imposed price floors on a number of agricultural products. The system of agricultural price floors—

The big problem with any attempt to impose a price floor is that it creates a surplus. To some extent the U.S. Department of Agriculture has tried to head off surpluses by taking steps to reduce supply; for example, by paying farmers not to grow crops. As a last resort, however, the U.S. government has been willing to buy up the surplus, taking the excess supply off the market.

But then what? The government can’t just sell the agricultural products: that would depress market prices, forcing the government to buy the stuff right back. So it has to give it away in ways that don’t depress market prices. One way to do this is by giving surplus food, free, to school lunch programs. These gifts are known as “bonus foods.” Along with financial aid, bonus foods allow many school districts to provide free or very cheap lunches to their students. Is this a story with a happy ending?

Not really. Nutritionists, concerned about growing child obesity in the United States, place part of the blame on those bonus foods. Schools get whatever the government has too much of—

Does a price floor always lead to an unwanted surplus? No. Just as in the case of a price ceiling, the floor may not be binding—

But suppose that a price floor is binding: what happens to the unwanted surplus? The answer depends on government policy. In the case of agricultural price floors, governments buy up unwanted surplus. As a result, the U.S. government has at times found itself warehousing thousands of tons of butter, cheese, and other farm products. The government then has to find a way to dispose of these unwanted goods.

Some countries pay exporters to sell products at a loss overseas; this is standard procedure for the European Union. The United States gives surplus food away to schools, which use the products in school lunches. In some cases, governments have actually destroyed the surplus production. To avoid the problem of dealing with the unwanted surplus, the U.S. government often pays farmers not to produce the products at all.

When the government is not prepared to purchase the unwanted surplus, a price floor means that would-

How a Price Floor Causes Inefficiency

The persistent surplus that results from a price floor creates missed opportunities—

Inefficiently Low QuantityBecause a price floor raises the price of a good to consumers, it reduces the quantity of that good demanded; because sellers can’t sell more units of a good than buyers are willing to buy, a price floor reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold below the market equilibrium quantity. Notice that this is the same effect as a price ceiling. You might be tempted to think that a price floor and a price ceiling have opposite effects, but both have the effect of reducing the quantity of a good bought and sold.

Price floors lead to inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: those who would be willing to sell the good at the lowest price are not always those who manage to sell it.

Inefficient Allocation of Sales Among SellersLike a price ceiling, a price floor can lead to inefficient allocation—but in this case inefficient allocation of sales among sellers rather than inefficient allocation to consumers.

An episode from the Belgian movie Rosetta, a realistic fictional story, illustrates the problem of inefficient allocation of selling opportunities quite well. Like many European countries, Belgium has a high minimum wage, and jobs for young people are scarce. At one point Rosetta, a young woman who is very eager to work, loses her job at a fast-

Wasted ResourcesAlso like a price ceiling, a price floor generates inefficiency by wasting resources. The most graphic examples involve government purchases of the unwanted surpluses of agricultural products caused by price floors. When the surplus production is simply destroyed, and when the stored produce goes, as officials euphemistically put it, “out of condition” and must be thrown away, it is pure waste.

Price floors also lead to wasted time and effort. Consider the minimum wage. Would-

Inefficiently High QualityAgain like price ceilings, price floors lead to inefficiency in the quality of goods produced.

Price floors often lead to inefficiency in that goods of inefficiently high quality are offered: sellers offer high-

We’ve seen that when there is a price ceiling, suppliers produce goods that are of inefficiently low quality: buyers prefer higher-

How can this be? Isn’t high quality a good thing? Yes, but only if it is worth the cost. Suppose that suppliers spend a lot to make goods of very high quality but that this quality isn’t worth much to consumers, who would rather receive the money spent on that quality in the form of a lower price. This represents a missed opportunity: suppliers and buyers could make a mutually beneficial deal in which buyers got goods of lower quality for a much lower price.

A good example of the inefficiency of excessive quality comes from the days when transatlantic airfares were set artificially high by international treaty. Forbidden to compete for customers by offering lower ticket prices, airlines instead offered expensive services, like lavish in-

Illegal ActivityFinally, like price ceilings, price floors provide incentives for illegal activity. For example, in countries where the minimum wage is far above the equilibrium wage rate, workers desperate for jobs sometimes agree to work off the books for employers who conceal their employment from the government—

So Why Are There Price Floors?

To sum up, a price floor creates various negative side effects:

- a persistent surplus of the good

- inefficiency arising from the persistent surplus in the form of inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and an inefficiently high level of quality offered by suppliers

- the temptation to engage in illegal activity, particularly bribery and corruption of government officials

So why do governments impose price floors when they have so many negative side effects? The reasons are similar to those for imposing price ceilings. Government officials often disregard warnings about the consequences of price floors either because they believe that the relevant market is poorly described by the supply and demand model or, more often, because they do not understand the model. Above all, just as price ceilings are often imposed because they benefit some influential buyers of a good, price floors are often imposed because they benefit some influential sellers.

13

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

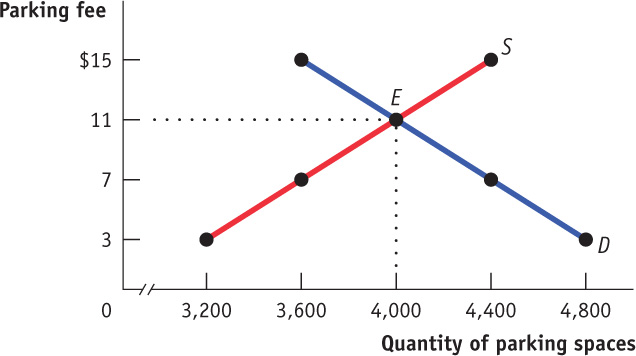

1. On game days, homeowners near Middletown University’s stadium used to rent parking spaces in their driveways to fans at a going rate of $11. A new town ordinance now sets a maximum parking fee of $7. Use the accompanying supply and demand diagram to explain how each of the following can result from the price ceiling.

-

a. Some homeowners now think it’s not worth the hassle to rent out spaces.

Fewer homeowners are willing to rent out their driveways because the price ceiling has reduced the payment they receive. This is an example of a fall in price leading to a fall in the quantity supplied. This is shown in the accompanying diagram by the movement from point E to point A along the supply curve, a reduction in quantity of 400 parking spaces. -

b. Some fans who used to carpool to the game now drive alone.

The quantity demanded increases by 400 spaces as the price decreases. At a lower price, more fans are willing to drive and rent a parking space. It is shown in the diagram by the movement from point E to point B along the demand curve. -

c. Some fans can’t find parking and leave without seeing the game.

Under a price ceiling, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied; as a result, shortages arise. In this case, there will be a shortage of 800 parking spaces. It is shown by the horizontal distance between points A and B.

Explain how each of the following adverse effects arises from the price ceiling.

-

d. Some fans now arrive several hours early to find parking.

Price ceilings result in wasted resources. The additional time fans spend to secure a parking space is wasted time. -

e. Friends of homeowners near the stadium regularly attend games, even if they aren’t big fans. But some serious fans have given up because of the parking situation.

Price ceilings lead to the inefficient allocation of goods— here, the parking spaces—to consumers. If less serious fans with connections end up with the parking spaces, diehard fans have no place to park. -

f. Some homeowners rent spaces for more than $7 but pretend that the buyers are non-

paying friends or family. Price ceilings lead to black markets.

2. True or false? Explain your answer. A price ceiling below the equilibrium price in an otherwise efficient market does the following:

-

a. increases quantity supplied

False. By lowering the price that producers receive, a price ceiling leads to a decrease in the quantity supplied. -

b. makes some people who want to consume the good worse off

True. A price ceiling leads to a lower quantity supplied than in an efficient, unregulated market. As a result, some people who would have been willing to pay the market price, and so would have gotten the good in an unregulated market, are unable to obtain it when a price ceiling is imposed. -

c. makes all producers worse off

True. Those producers who still sell the product now receive less for it and are therefore worse off. Other producers will no longer find it worthwhile to sell the product at all and so will also be made worse off.

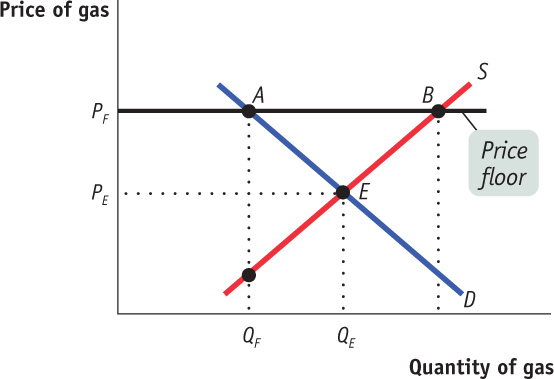

3. The state legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per gallon. Assess the following statements and illustrate your answer using the figure provided.

-

a. Proponents of the law claim it will increase the income of gas station owners. Opponents claim it will hurt gas station owners because they will lose customers.

Some gas station owners will benefit from getting a higher price. QF indicates the sales made by these owners. But some will lose; there are those who make sales at the market equilibrium price of PE but do not make sales at the regulated price of PF. These missed sales are indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A. -

b. Proponents claim consumers will be better off because gas stations will provide better service. Opponents claim consumers will be generally worse off because they prefer to buy gas at cheaper prices.

Those who buy gas at the higher price of PF will probably receive better service; this is an example of inefficiently high quality caused by a price floor as gas station owners compete on quality rather than price. But opponents are correct to claim that consumers are generally worse off—those who buy at PF would have been happy to buy at PE, and many who were willing to buy at a price between PE and PF are now unwilling to buy. This is indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A. -

c. Proponents claim that they are helping gas station owners without hurting anyone else. Opponents claim that consumers are hurt and will end up doing things like buying gas in a nearby state or on the black market.

Proponents are wrong because consumers and some gas station owners are hurt by the price floor, which creates “missed opportunities”—desirable transactions between consumers and station owners that never take place. Moreover, the inefficiency of wasted resources arises as consumers spend time and money driving to other states. The price floor also tempts people to engage in black market activity. With the price floor, only QF units are sold. But at prices between PE and PF, there are drivers who together want to buy more than QF and owners who are willing to sell to them, a situation likely to lead to illegal activity.

Multiple-

Question

1. To be effective, a price ceiling must be set

I. above the equilibrium price.

II. in the housing market.

III. to achieve the equilibrium market quantity.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

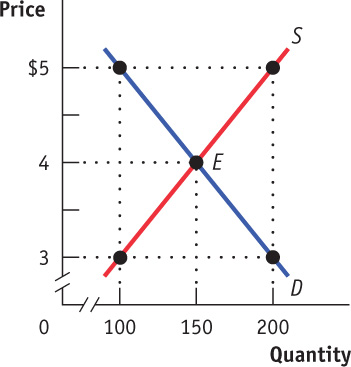

2. Refer to the graph provided. A price floor set at $5 will result in

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Effective price ceilings are inefficient because they

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

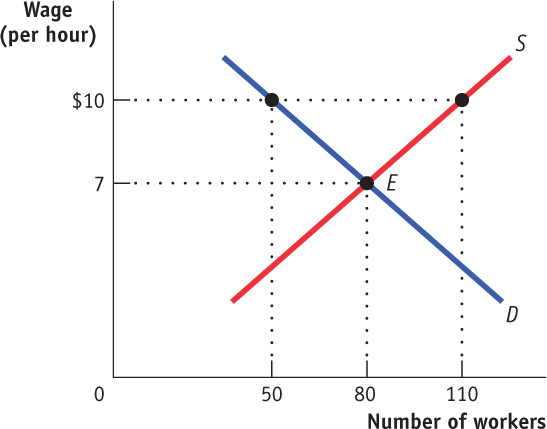

4. Refer to the graph provided. If the government establishes a minimum wage at $10, how many workers will benefit from the higher wage?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. Refer to the graph for question 4. With a minimum wage of $10, how many workers are unemployed (they would like to work, but are unable to find a job)?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

Draw a correctly labeled graph of a housing market in equilibrium. On your graph, illustrate an effective legal limit (ceiling) on rent. Identify the quantity of housing demanded, the quantity of housing supplied, and the size of the resulting surplus or shortage.

CEILINGS, FLOORS, AND QUANTITIES

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it looks like we can assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. Put another way, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it looks like we can assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. Put another way, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

NO, IT DOESN’T, BECAUSE BOTH FLOORS AND CEILINGS REDUCE THE QUANTITY BOUGHT AND SOLD. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—

NO, IT DOESN’T, BECAUSE BOTH FLOORS AND CEILINGS REDUCE THE QUANTITY BOUGHT AND SOLD. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—

To learn more, see price ceilings, floors, and inefficiency.