1.1 16Gains from Trade

(right) Scott Olson/Getty Images

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How comparative advantage leads to mutually beneficial international trade

How comparative advantage leads to mutually beneficial international trade

The sources of international comparative advantage

The sources of international comparative advantage

Who gains and who loses from international trade, and why the gains exceed the losses

Who gains and who loses from international trade, and why the gains exceed the losses

Comparative Advantage and International Trade

Goods and services purchased from other countries are imports; goods and services sold to other countries are exports.

The United States buys auto parts—

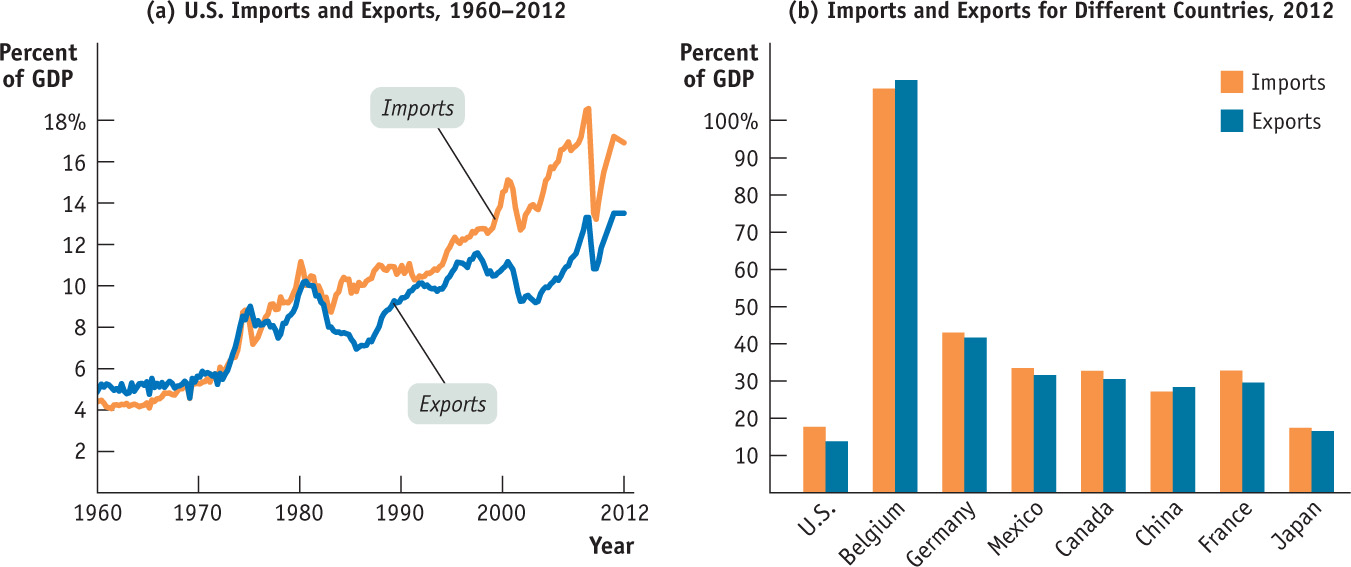

As illustrated by the opening story, imports and exports have taken on an increasingly important role in the U.S. economy. Over the last 50 years, both imports into and exports from the United States have grown faster than the U.S. economy as a whole. Panel (a) of Figure 16-1 shows how the values of U.S. imports and exports have grown as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Panel (b) shows imports and exports as a percentage of GDP for a number of countries. It shows that foreign trade is significantly more important for many other countries than it is for the United States. (Japan is the exception.)

FIGURE16-1The Growing Importance of International Trade

Globalization is the phenomenon of growing economic linkages among countries. Comparative Advantage and International Trade

Foreign trade isn’t the only way countries interact economically. In the modern world, investors from one country often invest funds in another nation; many companies are multinational, with subsidiaries operating in several countries; and a growing number of individuals work in a country different from the one in which they were born. The growth of all these forms of economic linkages among countries is often called globalization.

In this module and the next, however, we’ll focus mainly on international trade. To understand why international trade occurs and why economists believe it is beneficial to the economy, we will first review the concept of comparative advantage.

Production Possibilities and Comparative Advantage, Revisited

To produce auto parts, any country must use resources—

In some cases, it’s easy to see why the opportunity cost of producing a good is especially low in a given country. In other cases, matters are a bit less obvious. It’s as easy to produce auto parts in the United States as it is in Mexico, and Mexican auto parts workers are, if anything, less efficient than their U.S. counterparts. But Mexican workers are a lot less productive than U.S. workers in other areas, such as aircraft and chemical production. This means that diverting a Mexican worker into auto parts production reduces output of other goods less than diverting a U.S. worker into auto parts production. That is, the opportunity cost of producing auto parts in Mexico is less than it is in the United States.

So we say that Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing auto parts. Let’s repeat the definition of comparative advantage from Module 4: A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if the opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower for that country than for other countries.

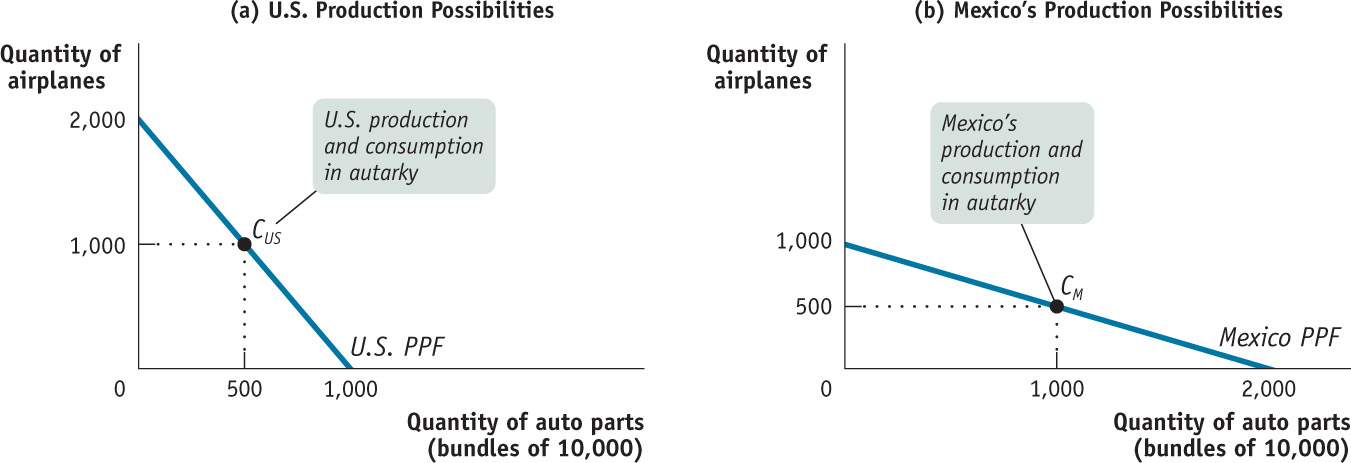

Figure 16-2 provides a hypothetical example of comparative advantage in international trade. We assume that only two goods are produced and consumed, auto parts and airplanes, and that there are only two countries in the world, the United States and Mexico. (In real life, auto parts aren’t worth much without auto bodies to put them in, but let’s set that issue aside). The figure shows hypothetical production possibility curves for the United States and Mexico.

FIGURE16-2Comparative Advantage and Production Possibilities

In Figure 16-2 we have grouped auto parts into bundles of 10,000, so, for example, a country that produces 500 bundles of auto parts is producing 5 million individual auto parts. You can see in the figure that the United States can produce 2,000 airplanes if it produces no auto parts, or 1,000 bundles of auto parts if it produces no airplanes. Thus, the slope of the U.S. production possibility curve, or PPF, is −2,000/1,000 = −2. That is, to produce an additional bundle of auto parts, the United States must forgo the production of 2 airplanes.

Similarly, Mexico can produce 1,000 airplanes if it produces no auto parts or 2,000 bundles of auto parts if it produces no airplanes. Thus, the slope of Mexico’s PPF is −1,000/2,000 = −1/2. That is, to produce an additional bundle of auto parts, Mexico must forgo the production of 1/2 an airplane.

Autarky is a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries.

Economists use the term autarky to refer to a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries. We assume that in autarky the United States chooses to produce and consume 500 bundles of auto parts and 1,000 airplanes. We also assume that in autarky Mexico produces 1,000 bundles of auto parts and 500 airplanes.

The trade-

16-1

U.S. and Mexican Opportunity Costs of Auto Parts and Airplanes

| U.S. Opportunity Cost | Mexican Opportunity Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 bundle of auto parts | 2 airplanes | > | 1/2 airplane |

| 1 airplane | 1/2 bundle of auto parts | < | 2 bundles of auto parts |

As we’ve learned, each country can do better by engaging in trade than it could by not trading. A country can accomplish this by specializing in the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage and exporting that good, while importing the good in which it has a comparative disadvantage. Let’s see how this works.

The Gains from International Trade

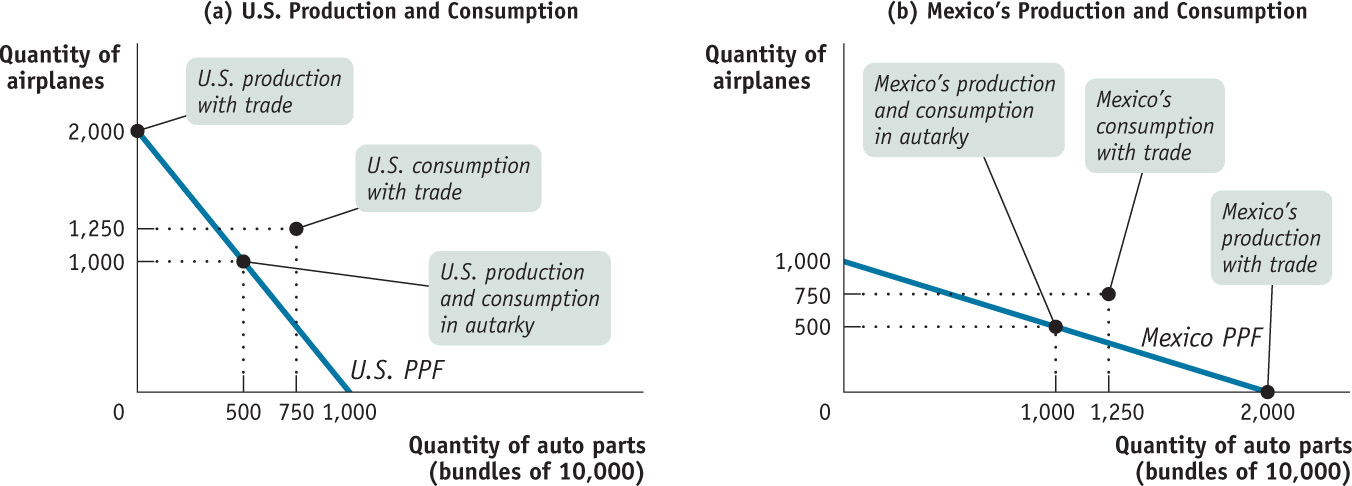

Figure 16-3 illustrates how both countries can gain from specialization and trade, by showing a hypothetical rearrangement of production and consumption that allows each country to consume more of both goods. Again, panel (a) represents the United States and panel (b) represents Mexico. In each panel we indicate again the autarky production and consumption assumed in Figure 16-2. Once trade becomes possible, however, everything changes. With trade, each country can move to producing only the good in which it has a comparative advantage—

FIGURE16-3The Gains from International Trade

Table 16-2 sums up the changes as a result of trade and shows why both countries can gain. The left part of the table shows the autarky situation, before trade, in which each country must produce the goods it consumes. The right part of the table shows what happens as a result of trade. After trade, the United States specializes in the production of airplanes, producing 2,000 airplanes and no auto parts; Mexico specializes in the production of auto parts, producing 2,000 bundles of auto parts and no airplanes.

16-2

How the United States and Mexico Gain from Trade

| In Autarky | With Trade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Consumption | Production | Consumption | Gains from trade | ||

| United States | Bundles of auto parts | 500 | 500 | 0 | 750 | +250 |

| Airplanes | 1,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 1,250 | +250 | |

| Mexico | Bundles of auto parts | 1,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 1,250 | +250 |

| Airplanes | 500 | 500 | 0 | 750 | +250 | |

The result is a rise in total world production of both goods. As you can see in the Table 16-2 column at far right showing consumption with trade, the United States is able to consume both more airplanes and more auto parts than before, even though it no longer produces auto parts, because it can import parts from Mexico. Mexico can also consume more of both goods, even though it no longer produces airplanes, because it can import airplanes from the United States.

The key to this mutual gain is the fact that trade liberates both countries from self-

Comparative Advantage versus Absolute Advantage

There’s nothing about Mexico’s climate or resources that makes it especially good at manufacturing auto parts. In fact, it almost surely takes fewer hours of labor to produce an auto seat in the United States than in Mexico. Why, then, do we buy Mexican auto parts?

Because the gains from trade depend on comparative advantage, not absolute advantage. Yes, it takes less labor to produce an auto seat in the United States than in Mexico. That is, the productivity of Mexican auto parts workers is less than that of their U.S. counterparts. But what determines comparative advantage is not the amount of resources used to produce a good but the opportunity cost of that good—

Here’s how it works: Mexican workers have low productivity compared with U.S. workers in the auto parts industry. But Mexican workers have even lower productivity compared with U.S. workers in other industries. Because Mexican labor productivity in industries other than auto parts is relatively lower, producing an auto seat in Mexico, even though it takes a lot of labor, does not require forgoing the production of large quantities of other goods.

In the United States, the opposite is true: very high productivity in other industries (such as high-

Mexico’s comparative advantage in auto parts is reflected in global markets by the wages Mexican workers are paid. That’s because a country’s wage rates, in general, reflect its labor productivity. In countries where labor is highly productive in many industries, employers are willing to pay high wages to attract workers, so competition among employers leads to an overall high wage rate. In countries where labor is less productive, competition for workers is less intense and wage rates are correspondingly lower.

The kind of trade that takes place between low-

Both fallacies miss the nature of gains from trade: it’s to the advantage of both countries if the poorer, lower-

It’s particularly important to understand that buying a good made by someone who is paid much lower wages than most U.S. workers doesn’t necessarily imply that you’re taking advantage of that person. It depends on the alternatives. Because workers in poor countries have low productivity across the board, they are offered low wages whether they produce goods exported to America or goods sold in local markets. A job that looks terrible by rich-

International trade that depends on low-

Sources of Comparative Advantage

International trade is driven by comparative advantage, but where does comparative advantage come from? Economists who study international trade have found three main sources of comparative advantage:

- international differences in climate

- international differences in factor endowments

- international differences in technology

1. Differences in ClimateIn general, differences in climate play a significant role in international trade. Tropical countries export tropical products like coffee, sugar, bananas, and shrimp. Countries in the temperate zones export crops like wheat and corn. Some trade is even driven by the difference in seasons between the northern and southern hemispheres: winter deliveries of Chilean grapes and New Zealand apples have become commonplace in U.S. and European supermarkets.

2. Differences in Factor EndowmentsCanada is a major exporter of forest products—

Forestland, like labor and capital, is a factor of production: an input used to produce goods and services. (Recall that the factors of production are land, labor, physical capital, and human capital.) Due to history and geography, the mix of available factors of production differs among countries, providing an important source of comparative advantage. The relationship between comparative advantage and factor availability is found in an influential model of international trade, the Heckscher–

The factor intensity of production of a good is a measure of which factor is used in relatively greater quantities than other factors in production.

According to the Heckscher–

Two key concepts in the model are factor abundance and factor intensity. Factor abundance refers to how large a country’s supply of a factor is relative to its supply of other factors. Factor intensity refers to the fact that producers use different ratios of factors of production in the production of different goods. For example, oil refineries use much more capital per worker than clothing factories. Economists use the term factor intensity to describe this difference among goods: oil refining is capital-

According to the Heckscher–

The basic intuition behind this result is simple and based on opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of a given factor—

The most dramatic example of the validity of the Heckscher–

3. Differences in TechnologyIn the 1970s and 1980s, Japan became by far the world’s largest exporter of automobiles, selling large numbers to the United States and the rest of the world. Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles wasn’t the result of climate. Nor can it easily be attributed to differences in factor endowments: aside from a scarcity of land, Japan’s mix of available factors is quite similar to that in other advanced countries. Instead, as we discussed in the Section 1 Business Case on lean production at Toyota and Boeing, Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was based on the superior production techniques developed by its manufacturers, which allowed them to produce more cars with a given amount of labor and capital than their American or European-

Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was a case of comparative advantage caused by differences in technology—

SKILL AND COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

In 1953 U.S. workers were clearly better equipped with machinery than their counterparts in other countries. Most economists at the time thought that America’s comparative advantage lay in capital-

The main resolution of this paradox, it turns out, depends on the definition of capital. U.S. exports aren’t intensive in physical capital—

In general, countries with highly educated workforces tend to export skill-

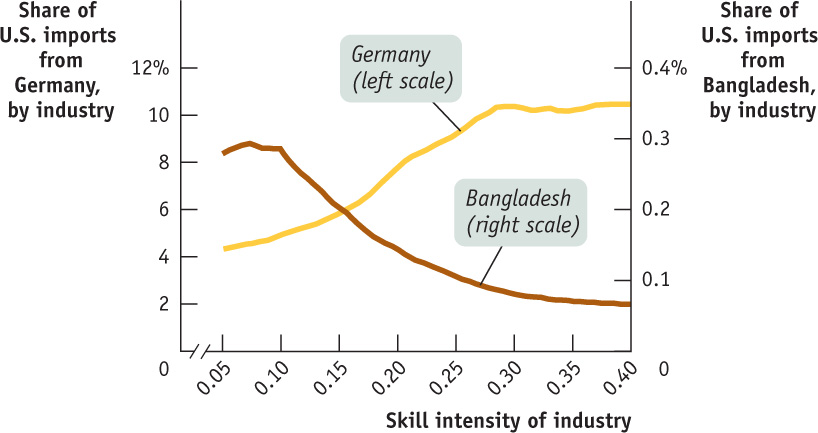

Figure 16-4 illustrates this point by comparing the goods the United States imports from Germany, a country with a highly educated labor force, with the goods the United States imports from Bangladesh, where about half of the adult population is still illiterate. In each country industries are ranked, first, according to how skill-

FIGURE16-4Education, Skill Intensity, and Trade

In Figure 16-4, the horizontal axis shows a measure of the skill intensity of different industries, and the vertical axes show the share of U.S. imports in each industry coming from Germany (on the left) and Bangladesh (on the right). As you can see, each country’s share of U.S. imports reflects its skill level. The curve representing Germany slopes upward: the more skill-

16

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

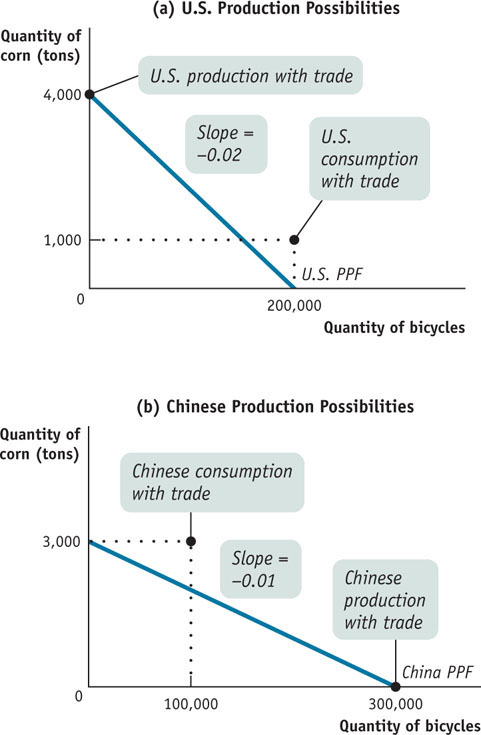

1. In the United States, the opportunity cost of 1 ton of corn is 50 bicycles. In China, the opportunity cost of 1 bicycle is 0.01 ton of corn.

-

a. Determine the pattern of comparative advantage.

To determine comparative advantage, we must compare the two countries’ opportunity costs for a given good. Take the opportunity cost of 1 ton of corn in terms of bicycles. In China, the opportunity cost of 1 bicycle is 0.01 ton of corn; so the opportunity cost of 1 ton of corn is 1/0.01 bicycles = 100 bicycles. The United States has the comparative advantage in corn since its opportunity cost in terms of bicycles is 50, a smaller number. Similarly, the opportunity cost in the United States of 1 bicycle in terms of corn is 1/50 ton of corn = 0.02 ton of corn. This is greater than 0.01, the Chinese opportunity cost of 1 bicycle in terms of corn, implying that China has a comparative advantage in bicycles. -

b. In autarky, the United States can produce 200,000 bicycles if no corn is produced, and China can produce 3,000 tons of corn if no bicycles are produced. Draw each country’s production possibility curve assuming constant opportunity cost, with tons of corn on the vertical axis and bicycles on the horizontal axis.

Given that the United States can produce 200,000 bicycles if no corn is produced, it can produce 200,000 bicycles × 0.02 ton of corn/bicycle = 4,000 tons of corn when no bicycles are produced. Likewise, if China can produce 3,000 tons of corn if no bicycles are produced, it can produce 3,000 tons of corn × 100 bicycles/ton of corn = 300,000 bicycles if no corn is produced. These points determine the vertical and horizontal intercepts of the U.S. and Chinese production possibilities, as shown in the accompanying diagram.

-

c. With trade, each country specializes its production. The United States consumes 1,000 tons of corn and 200,000 bicycles; China consumes 3,000 tons of corn and 100,000 bicycles. Indicate the production and consumption points on your diagrams, and use them to explain the gains from trade.

The diagram shows the production and consumption points of the two countries. Each country is clearly better off with international trade because each now consumes a bundle of the two goods that lies outside its own production possibility curve, indicating that these bundles were unattainable in autarky.

2. Explain the following patterns of trade using the Heckscher–

-

a. France exports wine to the United States, and the United States exports movies to France.

The resources required to produce wine are more abundant in France, while the resources required to produce movies are abundant in the U.S. As a result, France exports wine to the United States, and the United States exports movies to France. -

b. Brazil exports shoes to the United States, and the United States exports shoe-

making machinery to Brazil. The resources required to produce shoes, such as labor, are more abundant in Brazil, while the U.S. has the resources to produce shoe-making machinery. As a result, Brazil exports shoes to the United States, and the United States exports shoe-making machinery to Brazil.

Multiple-

Question

1. Globalization can be defined as

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

2. Which of the following are sources of comparative advantage?

I. Differences in climate

II. Differences in factor endowments

III. Superior production techniques

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

3. Which statement about wage rates is correct?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

4. Which of the following best describes a country in autarky?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question

5. According to the Heckscher–

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Critical-

In autarky, the equilibrium price of a good in the domestic market is $10. If the world price of the same good is $8 and the country opens up to trade, how will the domestic quantity supplied and demanded be affected? Will the country be an importer or an exporter of the good?