1.2 Module 17: Supply, Demand, and International Trade

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

How tariffs and import quotas cause inefficiency and reduce total surplus

How tariffs and import quotas cause inefficiency and reduce total surplus

Why governments often engage in trade protection to shelter domestic industries from imports

Why governments often engage in trade protection to shelter domestic industries from imports

About the challenges that have been created by globalization

About the challenges that have been created by globalization

Imports, Exports, and Wages

Simple models of comparative advantage are helpful for understanding the fundamental causes of international trade. However, to analyze the effects of international trade at a more detailed level and to understand trade policy, it helps to return to the supply and demand model. We’ll start by looking at the effects of imports on domestic producers and consumers, then turn to the effects of exports.

The Effects of Imports

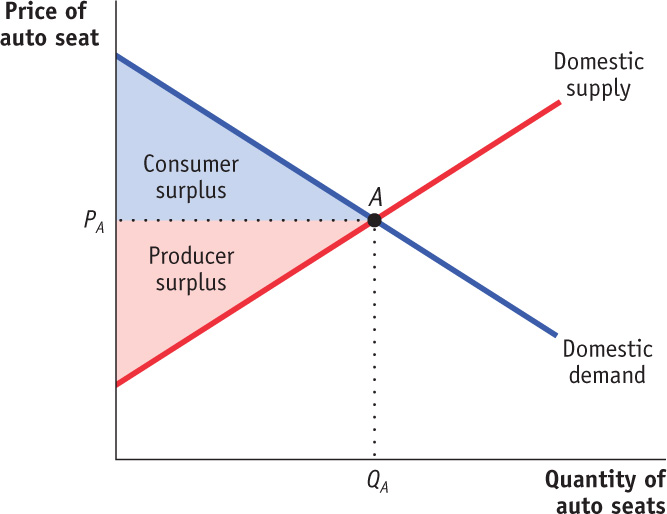

Figure 17-1 shows the U.S. market for auto seats, ignoring international trade for a moment. It introduces a few new concepts: the domestic demand curve, the domestic supply curve, and the domestic or autarky price.

The domestic demand curve shows how the quantity of a good demanded by domestic consumers depends on the price of that good.

The domestic supply curve shows how the quantity of a good supplied by domestic producers depends on the price of that good.

The domestic demand curve shows how the quantity of a good demanded by residents of a country depends on the price of that good. Why “domestic”? Because people living in other countries may demand the good, too. Once we introduce international trade, we need to distinguish between purchases of a good by domestic consumers and purchases by foreign consumers. So the domestic demand curve reflects only the demand of residents of our own country. Similarly, the domestic supply curve shows how the quantity of a good supplied by producers inside our own country depends on the price of that good. Once we introduce international trade, we need to distinguish between the supply of domestic producers and foreign supply—

In autarky, with no international trade in auto seats, the equilibrium in this market would be determined by the intersection of the domestic demand and domestic supply curves, point A. The equilibrium price of auto seats would be PA, and the equilibrium quantity of auto seats produced and consumed would be QA. As always, both consumers and producers gain from the existence of the domestic market. In autarky, consumer surplus would be equal to the area of the blue-

The world price of a good is the price at which that good can be bought or sold abroad.

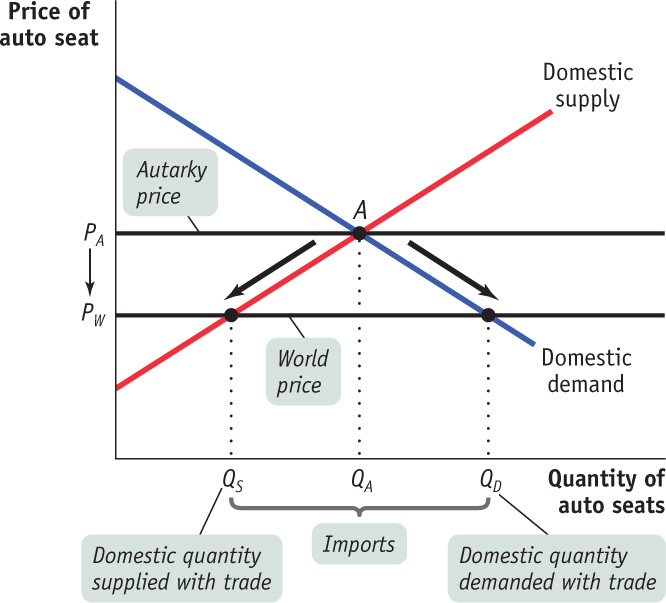

Now let’s imagine opening up this market to imports. To do this, we must make an assumption about the supply of imports. The simplest assumption, which we will adopt here, is that unlimited quantities of auto seats can be purchased from abroad at a fixed price, known as the world price of auto seats. Figure 17-2 shows a situation in which the world price of an auto seat, PW, is lower than the price of an auto seat that would prevail in the domestic market in autarky, PA.

Given that the world price is below the domestic price of an auto seat, it is profitable for importers to buy auto seats abroad and resell them domestically. The imported auto seats increase the supply of auto seats in the domestic market, driving down the domestic market price. Auto seats will continue to be imported until the domestic price falls to a level equal to the world price.

The result is shown in Figure 17-2. Because of imports, the domestic price of an auto seat falls from PA to PW. The quantity of auto seats demanded by domestic consumers rises from QA to QD, and the quantity supplied by domestic producers falls from QA to QS. The difference between the domestic quantity demanded and the domestic quantity supplied, QD − QS, is filled by imports.

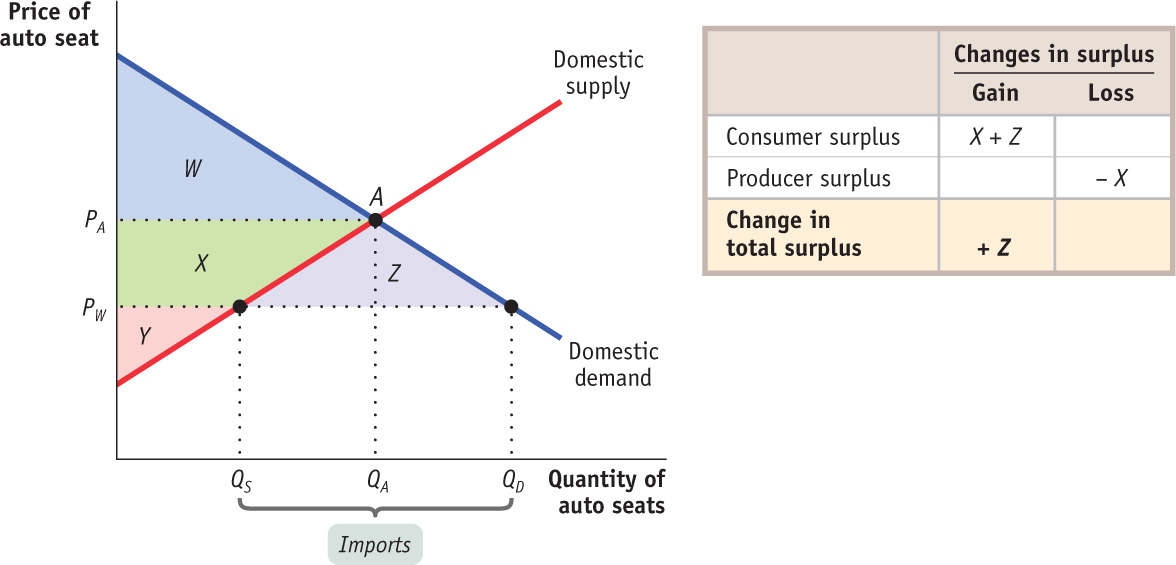

Now let’s turn to the effects of imports on consumer surplus and producer surplus. Because imports of auto seats lead to a fall in their domestic price, consumer surplus rises and producer surplus falls. Figure 17-3 shows how this works. We label four areas: W, X, Y, and Z. The autarky consumer surplus we identified in Figure 17-1 corresponds to W, and the autarky producer surplus corresponds to the sum of X and Y. The fall in the domestic price to the world price leads to an increase in consumer surplus; it increases by X and Z, so consumer surplus now equals the sum of W, X, and Z. At the same time, producers lose X in surplus, so producer surplus now equals only Y.

The table in Figure 17-3 summarizes the changes in consumer and producer surplus when the auto seats market is opened to imports. Consumers gain surplus equal to the areas X + Z. Producers lose surplus equal to X. So the sum of producer and consumer surplus—

This is an important result. We have just shown that opening up a market to imports leads to a net gain in total surplus, which is what we should have expected given the proposition that there are gains from international trade.

However, we have also learned that although the country as a whole gains, some groups—

We turn next to the case in which a country exports a good.

The Effects of Exports

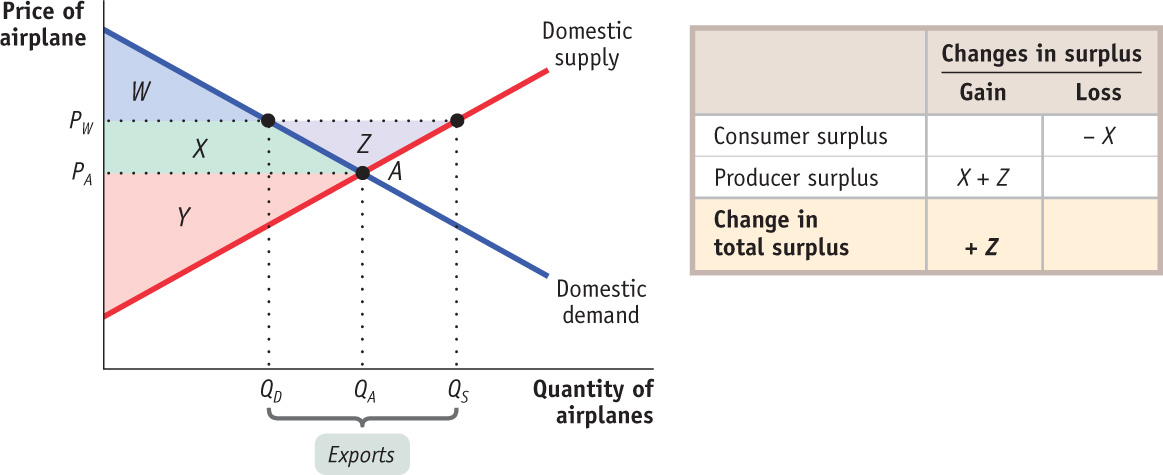

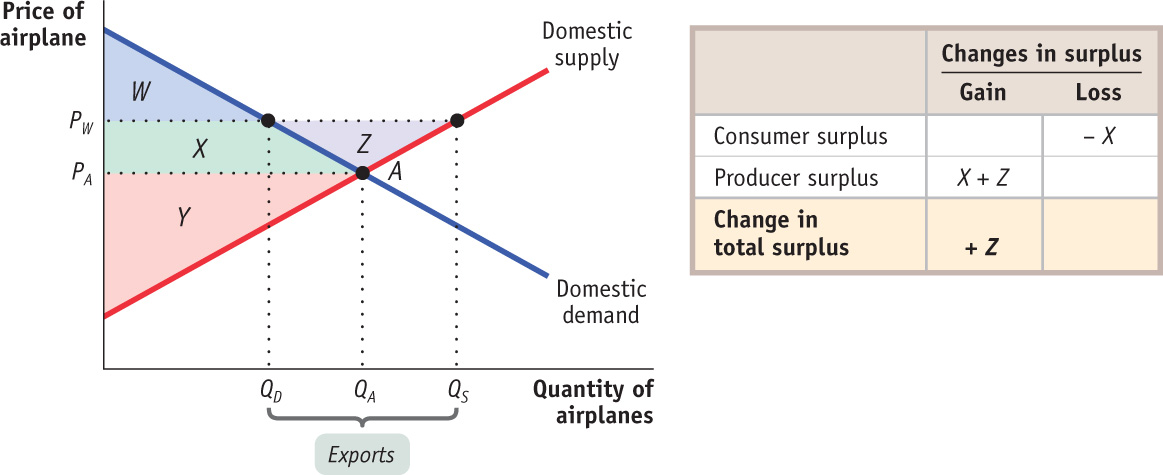

Figure 17-4 shows the effects on a country when it exports a good, in this case airplanes. For this example, we assume that unlimited quantities of airplanes can be sold abroad at a given world price, PW, which is higher than the price that would prevail in the domestic market in autarky, PA.

The higher world price makes it profitable for exporters to buy airplanes domestically and sell them overseas. The purchases of domestic airplanes drive the domestic price up until it is equal to the world price. As a result, the quantity demanded by domestic consumers falls from QA to QD and the quantity supplied by domestic producers rises from QA to QS. This difference between domestic production and domestic consumption, QS − QD, is exported.

Like imports, exports lead to an overall gain in total surplus for the exporting country but also create losers as well as winners. Figure 17-5 shows the effects of airplane exports on producer and consumer surplus. In the absence of trade, the price of each airplane would be PA. Consumer surplus in the absence of trade is the sum of areas W and X, and producer surplus is area Y. As a result of trade, price rises from PA to PW, consumer surplus falls to W, and producer surplus rises to Y + X + Z. So producers gain X + Z, consumers lose X, and, as shown in the table accompanying the figure, the economy as a whole gains total surplus in the amount of Z.

We have learned, then, that imports of a particular good hurt domestic producers of that good but help domestic consumers, whereas exports of a particular good hurt domestic consumers of that good but help domestic producers. In each case, the gains are larger than the losses.

International Trade and Wages

So far we have focused on the effects of international trade on producers and consumers in a particular industry. For many purposes this is a very helpful approach. However, producers and consumers are not the only parts of society affected by trade—

Moreover, the effects of trade aren’t limited to just those industries that export or compete with imports because factors of production can often move between industries. So now we turn our attention to the long-

To begin our analysis, consider the position of Maria, an accountant at Midwest Auto Parts, Inc. If the economy is opened up to imports of auto parts from Mexico, the domestic auto parts industry will contract, and it will hire fewer accountants.

But accounting is a profession with employment opportunities in many industries, and Maria might well find a better job in the aircraft industry, which expands as a result of international trade. So it may not be appropriate to think of her as a producer of auto parts who is hurt by competition from imported parts. Rather, we should think of her as an accountant who is affected by auto part imports only to the extent that these imports change the wages of accountants in the economy as a whole.

The wage rate of accountants is a factor price—the price employers have to pay for the services of a factor of production. One key question about international trade is how it affects factor prices—

In the previous module we described the Heckscher–

We won’t work this out in detail, but the idea is simple. The prices of factors of production, like the prices of goods and services, are determined by supply and demand. If international trade increases the demand for a factor of production, that factor’s price will rise; if international trade reduces the demand for a factor of production, that factor’s price will fall.

Exporting industries produce goods and services that are sold abroad.

Import-

Now think of a country’s industries as consisting of two kinds: exporting industries, which produce goods and services that are sold abroad, and import-

In addition, the Heckscher–

As we’ve seen, U.S. exports tend to be human-

This effect has been a source of much concern in recent years. Wage inequality—

The effects of trade on wages in the United States have generated considerable controversy in recent years. Most economists who have studied the issue agree that growing imports of labor-

The Effects of Trade Protection

An economy has free trade when the government does not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand.

Ever since the principle of comparative advantage was laid out in the early nineteenth century, most economists have advocated free trade. That is, they have argued that government policy should not attempt either to reduce or to increase the levels of exports and imports that occur naturally as a result of supply and demand.

Policies that limit imports are known as trade protection or simply as protection.

Despite the free-

Let’s look at the two most common protectionist policies, tariffs and import quotas, then turn to the reasons governments follow these policies.

The Effects of a Tariff

A tariff is a tax levied on imports.

A tariff is a form of excise tax, one that is levied only on sales of imported goods. For example, the U.S. government could declare that anyone bringing in auto seats must pay a tariff of $100 per unit. In the distant past, tariffs were an important source of government revenue because they were relatively easy to collect. But in the modern world, tariffs are usually intended to discourage imports and protect import-

The tariff raises both the price received by domestic producers and the price paid by domestic consumers. Suppose, for example, that our country imports auto seats, and an auto seat costs $200 on the world market. As we saw earlier, under free trade the domestic price would also be $200. But if a tariff of $100 per unit is imposed, the domestic price will rise to $300, because it won’t be profitable to import auto seats unless the price in the domestic market is high enough to compensate importers for the cost of paying the tariff.

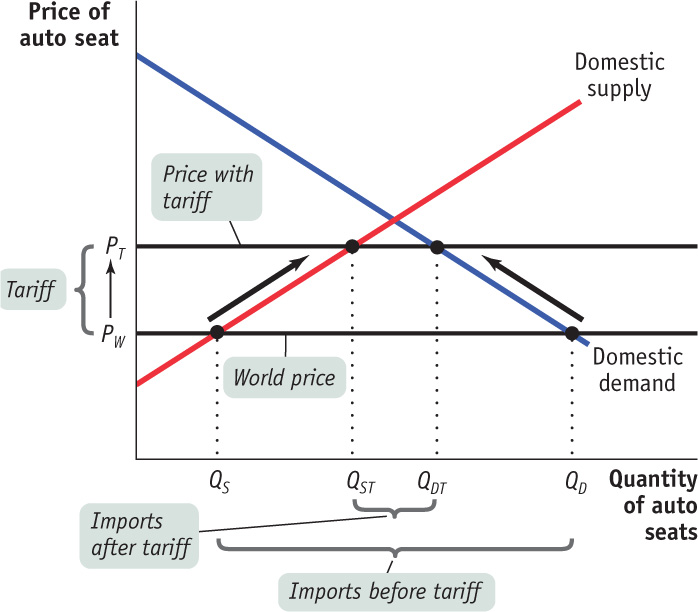

Figure 17-6 illustrates the effects of a tariff on imports of auto seats. As before, we assume that PW is the world price of an auto seat. Before the tariff is imposed, imports have driven the domestic price down to PW, so that pre-

Now suppose that the government imposes a tariff on each auto seat imported. As a consequence, it is no longer profitable to import auto seats unless the domestic price received by the importer is greater than or equal to the world price plus the tariff. So the domestic price rises to PT, which is equal to the world price, PW, plus the tariff. Domestic production rises to QST, domestic consumption falls to QDT, and imports fall to QDT − QST.

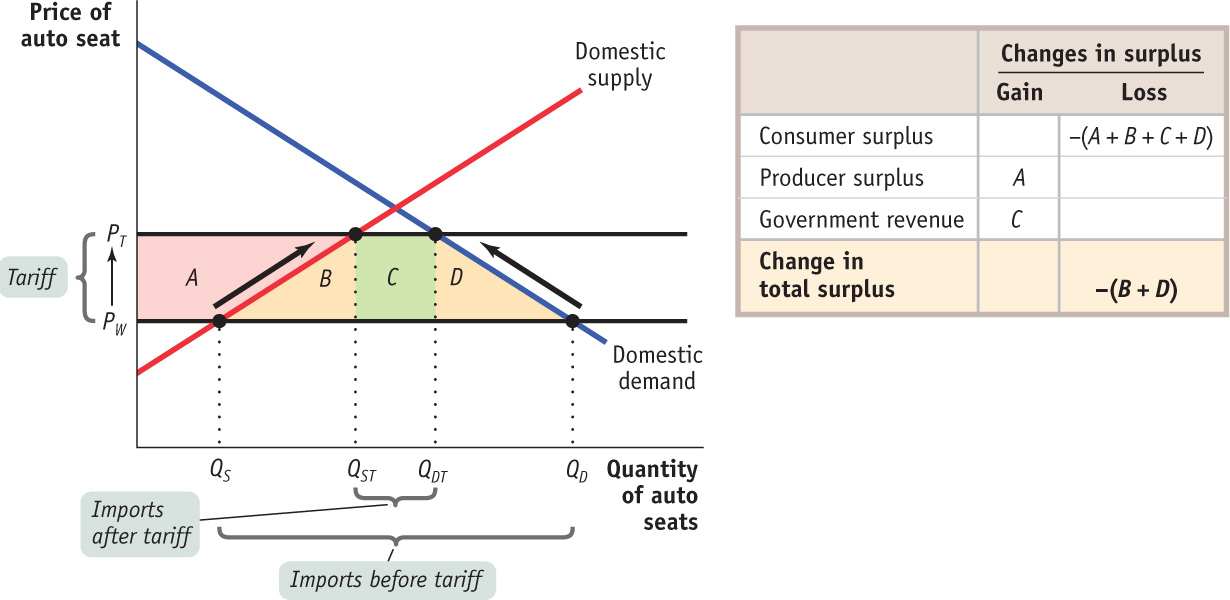

A tariff, then, raises domestic prices, leading to increased domestic production and reduced domestic consumption compared to the situation under free trade. Figure 17-7 shows the effects on surplus. There are three effects:

- The higher domestic price increases producer surplus, a gain equal to area A.

- The higher domestic price reduces consumer surplus, a reduction equal to the sum of areas A, B, C, and D.

- The tariff yields revenue to the government. How much revenue? The government collects the tariff—

which, remember, is equal to the difference between PT and PW on each of the QDT − QST units imported. So total revenue is (PT − PW) × (QDT − QST). This is equal to area C.

The welfare effects of a tariff are summarized in the table in Figure 17-7. Producers gain, consumers lose, and the government gains. But consumer losses are greater than the sum of producer and government gains, leading to a net reduction in total surplus equal to areas B + D.

An excise tax creates inefficiency, or deadweight loss, because it prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring. The same is true of a tariff, where the deadweight loss imposed on society is equal to the loss in total surplus represented by areas B + D.

Tariffs generate deadweight losses because they create inefficiencies in two ways:

- Some mutually beneficial trades go unexploited: some consumers who are willing to pay more than the world price, PW, do not purchase the good, even though PW is the true cost of a unit of the good to the economy. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 17-7 by area D.

- The economy’s resources are wasted on inefficient production: some producers whose cost exceeds PW produce the good, even though an additional unit of the good can be purchased abroad for PW. The cost of this inefficiency is represented in Figure 17-7 by area B.

The Effects of an Import Quota

An import quota is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported.

An import quota, another form of trade protection, is a legal limit on the quantity of a good that can be imported. For example, a U.S. import quota on Mexican auto seats might limit the quantity imported each year to 500,000 units. Import quotas are usually administered through licenses: a number of licenses are issued, each giving the license-

A quota on sales has the same effect as an excise tax, with one difference: the money that would otherwise have accrued to the government as tax revenue under an excise tax becomes license-

Look again at Figure 17-7. An import quota that limits imports to QDT − QST will raise the domestic price of auto parts by the same amount as the tariff we considered previously. That is, it will raise the domestic price from PW to PT. However, area C will now represent quota rents rather than government revenue.

Who receives import licenses and so collects the quota rents? In the case of U.S. import protection, the answer may surprise you: the most important import licenses—

Because the quota rents for most U.S. import quotas go to foreigners, the cost to the nation of such quotas is larger than that of a comparable tariff (a tariff that leads to the same level of imports). In Figure 17-7 the net loss to the United States from such an import quota would be equal to areas B + C + D, the difference between consumer losses and producer gains.

Challenges to Globalization

The forward march of globalization over the past century is generally considered a major political and economic success. Economists and policy makers alike have viewed growing world trade, in particular, as a good thing.

We would be remiss, however, if we failed to acknowledge that many people are having second thoughts about globalization. To a large extent, these second thoughts reflect two concerns shared by many economists: worries about the effects of globalization on inequality and worries that new developments, in particular the growth in offshore outsourcing, are increasing economic insecurity.

Globalization and Inequality

We’ve already mentioned the implications of international trade for factor prices, such as wages: when wealthy countries like the United States export skill-

Trade with China, in particular, raises concerns among labor groups trying to maintain wage levels in rich countries. Although China has experienced spectacular economic growth since the economic reforms that began in the late 1970s, it remains a poor, low-

Outsourcing

Chinese exports to the United States overwhelmingly consist of labor-

Offshore outsourcing takes place when businesses hire people in another country to perform various tasks.

Now, modern telecommunications make it possible to engage in offshore outsourcing, in which businesses hire people in another country to perform various tasks. The classic example is a call center: the person answering the phone when you call a company’s 1-

Although offshore outsourcing has come as a shock to some U.S. workers, such as programmers whose jobs have been outsourced to India, it’s still relatively small compared with more traditional trade. Some economists have warned, however, that millions or even tens of millions of workers who have never thought they could face foreign competition for their jobs may face unpleasant surprises in the not-

Concerns about income distribution and outsourcing, as we’ve said, are shared by many economists. There is also, however, widespread opposition to globalization in general, particularly among college students.

What motivates the antiglobalization movement? To some extent it’s the sweatshop labor fallacy: it’s easy to get outraged about the low wages paid to the person who made your shirt, and harder to appreciate how much worse off that person would be if denied the opportunity to sell goods in rich countries’ markets.

It’s also true, however, that the movement represents a backlash against supporters of globalization who have oversold its benefits. Countries in Latin America, in particular, were promised that reducing their tariff rates would produce an economic takeoff; instead, they have experienced disappointing results.

Do these challenges to globalization undermine the argument that international trade is a good thing? The great majority of economists would argue that the gains from reducing trade protection still exceed the losses. However, it has become more important than before to make sure that the gains from international trade are widely spread. And the politics of international trade is becoming increasingly difficult as the extent of trade has grown.

!world_eia!BEEFING UP EXPORTS

In December 2010, negotiators from the United States and South Korea reached final agreement on a free-

What made this deal possible? Estimates by the U.S. International Trade Commission found that the deal would raise average American incomes, although modestly: the commission put the gains at around one-

These overall gains played little role in the politics of the deal, however, which hinged on losses and gains for particular U.S. constituencies. Some opposition to the deal came from labor, especially from autoworkers, who feared that eliminating the 8% U.S. tariff on imports of Korean automobiles would lead to job losses.

But there were also interest groups in America that badly wanted the deal, most notably the beef industry: Koreans are big beef-

And the Obama administration definitely wanted a deal, in part for reasons unrelated to economics: South Korea is an important U.S. ally, and military tensions with North Korea had been ratcheting up. So a trade deal was viewed in part as a symbol of U.S.–South Korean cooperation. Even labor unions weren’t as opposed as they might have been.

It also helped that South Korea—

Module 17 Review

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. Suppose the world price of butter is $0.50 per pound and the domestic price in autarky is $1.00 per pound. Use a diagram similar to Figure 17-7 to show the following.

-

a. If there is free trade, domestic butter producers want the government to impose a tariff of no less than $0.50 per pound.

-

b. What happens if a tariff greater than $0.50 per pound is imposed?

2. Suppose the government imposes an import quota rather than a tariff on butter. What quota limit would generate the same quantity of imports as a tariff of $0.50 per pound?

3. Due to a strike by truckers, trade in food between the United States and Mexico is halted. In autarky, the price of Mexican grapes is lower than that of U.S. grapes. Using a diagram of the U.S. domestic demand curve and the U.S. domestic supply curve for grapes, explain the effect of these events on the following.

-

a. U.S. grape consumers’ surplus

-

b. U.S. grape producers’ surplus

-

c. U.S. total surplus

4. What effect do you think the event described in question 3 will have on Mexican grape producers? Mexican grape pickers? Mexican grape consumers? U.S. grape pickers?

Multiple-

Question

PV385SWFyf88antgHPiy4oHwJsyRCiK1nicXM1W2tKJkEL6JOKF3vqXiahMxkLvXvOola4d9cU1GmZxyvh+1ObDDiiADeq3LLV9mq3M42YKt1f0fHKWpb0qUX8h2+OlR9aVAQpcbY65ESBfg4VyhsZkyzBc9DBfRYLJhBmlIP4E7eOyrGg6yyQhH9QDnNywJkKqXedwf86SH/i3aG0KewNrAOJPDZKJXIATJYhhGGVVXdmfwf6IBRcigjXe/ADpeV8tBcQqO4CktIB7kHE6JFenJWfg6l9gVpewzX+snEri+NR+kEHjPDJzXn00eF0RZgmFEymmSNbGz8x7q60RDCMOaAP6jak8/LJigKKabPbjd8UFb7W+r3QwH13bVF0KLwMFyFKF4AanXzf1b2kMKnxElI+AMwh6P7W41xR0bC52lj8vC5O5AlKuPQnEWocvxoeojUYHRVQNjD+4fcfwz//pcydD6lkIROXb4fnpd1YJVDKtWt/upOBXAT1RppExKpb64KYXksYQHX3Vz95vmWz5MAqi3wPcLu1bTn99fRZjhViJtRAojPgaU7VI=Question

y1/a5gELwZA/qRAbixE2fnFwvVKWevAhLfZjnRFVGlCza2exqRW8YL3WOaITeiFEbeDGJgx652xx92gecAaViGI5ZYVWQmgAwbY+IUqXmdsPVNKnBwq+WdZbSukXsQa3SOIB/mMCB1PC35LSoHav4Tl23q8B1xF2UEsFFf1fx1Z153Wcf8ImTTZZsB9r8Fy5o78sHCBOPZEZPvycQIBeU11lV2WIY7r36P/O3jJMHV/jv82za4Dz8Ps3U+59y9Yzh5UTIE9rvER2z3euXLofO7/N4XDYK6SU8TM6DU50b7kjS3p/3cr+8Kmxd/J4oF6NY9gG4bGRlgQNcnyhjvWFERjI40l34cZI8DlV7Sxrt1HE1iLjWZsXdvnbvq8L81lg8Eb++CRBGRv92vpmgqWFHIviDZMzxQXi3yFV1T62dYT32glRsGJCJbpdbR4BxiKmi+XfNTOhP/y4jf34ZuwELuh9bxrY/nJYGHcFFZzSc4/rEFUUDDc/XvqhAprap8R5pxEmGb2R8dsjkZ9M5eEpxQHvKx9GQl0+f2a3AMKyFLUe0vEjfVKvV3TpHEA=Question

NE7MFlhW/syYBkF4BkUry5UrUesB/lUR+Cwn+Q8/ekhJj0LOZ+dw1EMn29DTwHI3mSnn99UcgTVjNx4Y1otpHU10xSVbhofr9jqcWbA3h4dVEeM5rBwqHY5rCB6A3elYdijoLZkXkU3x/GMel/CvvuhJ8RhevUm3DvC6ti9yRpBcDiO+H/pxlARMb6RogdYXYxAQBON+s17outVm/xThz8135uQx1bIuQ6T0V0xVDziJsmFL7lt1nZjI80rb4I7/pK/yXGirc1ul9qQyMf+0kSmogWiqy+RwIrKH8zw8SNvZmglQZJC3vd6MrSKmCgjHvWAKckGcud3nrCU+FCHUNMnMyS6qrjLv6xk0irMgaiqeWqHPqRJX9QxC8BP5nJbz75fUMh2Pif8qOkl0hxPirfZ1qM/A38W23FX4zn0JwLYUosPX34Fg3EwUcNG6pP1GtT7KRw3HBRRCRe0PGpCPZscbFOCX8PPAvdyngu23MKo0TvVArW52QaHaPUHWSvcy23Ovta7LdJthG2v6Question

Fug3JqSTjU4zqrxUCvFOc7d1zF5bkAQTEbDJSb0SCqNT++iiPwvF8XzDzdymRyHrvutnDuSY07/VVm/qAzRQDhzegSAXxw11hgon9SsswDrlwj4K3ulWKPl0i1Fp5W9Kp/gWFGkpg3U/MF6KjdAd+CTtVJmrIlV3kkX3H0Xf97XgEGv8ZLp4PNfH7GwBYUGCduSnQ/8DiLHBY+KyZiqfhdkrUoGyTpIGCWFsC/0KdreRXD5GqobMOpbCoZp+KBO6bKtqpvRh8uS7ihnVHlJmgjRBcl4sm6TJR62MI0Vw42ZimusuMoGhYOWzyiVz+E+V6+JLYCvTJN9KJ1of8wHY67/UJHB4Ox1gsPJhD7G2gTgw3RPSUT1/j/gzfVmxkCfqhlBDKscJvDD/wIv0Ox/TRaSKVWVABJaTKwFgTg/dgnKz5Fzwr8WKjo6xOf89PhzUW+5+xMc4iwmQpga6ww7h3AcQ86GVUuJjBAGYD0/nu8kmGTv8BJnf9rIoikv3EyByujs2677yJkv5AC+8gmupvQ==Question

QpvdS3sfZRe3PwA1pTlAKpZO81P6vzWKDGF2BumBcqzreBca6sjtOCtRQ1U2dcLpz3AL8zcuc52/uhXyhiUEO9ksAbzvvdMNjXDg5YE/CD3sNIsbKN2xQTmYbrShJzcrlrDey9gAOmaTRUQmlX6BR2r9s0H/eYvZPXYEVDGIpKa12JDoeLZAd6Xmyhxxj1WYKd7i7dTo6PVWoKL6ZXdazzQtmHGFl3jgTcfCDk4C6J4jnjhr1hLpVHfNsQmjZPxAckBh23lE98EmPBTop1dd0NnFvRyOArgQcQp19zwoMGrQL3dMPALSQDH+2hI65my4UtcgYMOhzYmQHBh/hfLyBkea4Q/VGQdQGExFKWEwTAStt12HqsKaSqz1l5uzULeBawtepC7CiCHBYa4fRcje6YXhVEIgk+YQbS3rDGVhbUrHYeRn8pOLDoRMWNxLegbECritical-

A few years ago, the United States imposed tariffs on steel imports, which are an input in a large number and variety of U.S. industries. Explain why political lobbying to eliminate these tariffs is more likely to be effective than political lobbying to eliminate tariffs on consumer goods such as sugar or clothing.