1.4 27Long-Run Outcomes in Perfect Competition

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

Why industries behave differently in the short run and the long run

Why industries behave differently in the short run and the long run

What determines the industry supply curve in both the short run and the long run

What determines the industry supply curve in both the short run and the long run

Up to this point we have been discussing the perfectly competitive firm’s short-

The Industry Supply Curve

The industry supply curve shows the relationship between the price of a good and the total output of the industry as a whole.

Why will an increase in the demand for organic tomatoes lead to a large price increase at first but a much smaller increase in the long run? The answer lies in the behavior of the industry supply curve—the relationship between the price and the total output of an industry as a whole. The industry supply curve is what we referred to in earlier modules as the supply curve or the market supply curve. But here we take some extra care to distinguish between the individual supply curve of a single firm and the supply curve of the industry as a whole.

As you might guess from the previous module, the industry supply curve must be analyzed in somewhat different ways for the short run and the long run. Let’s start with the short run.

The Short-Run Industry Supply Curve

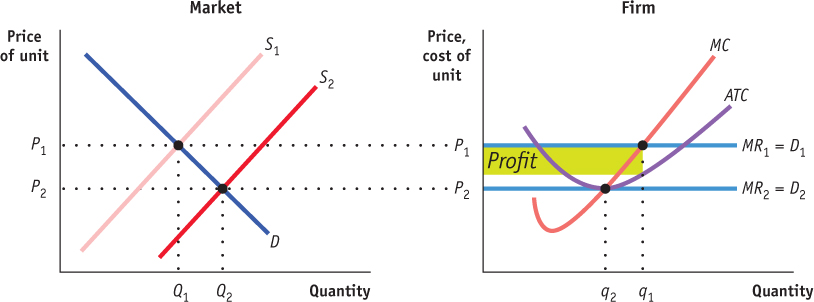

Recall that in the short run the number of firms in an industry is fixed—

Each of these 100 farms will have an individual short-

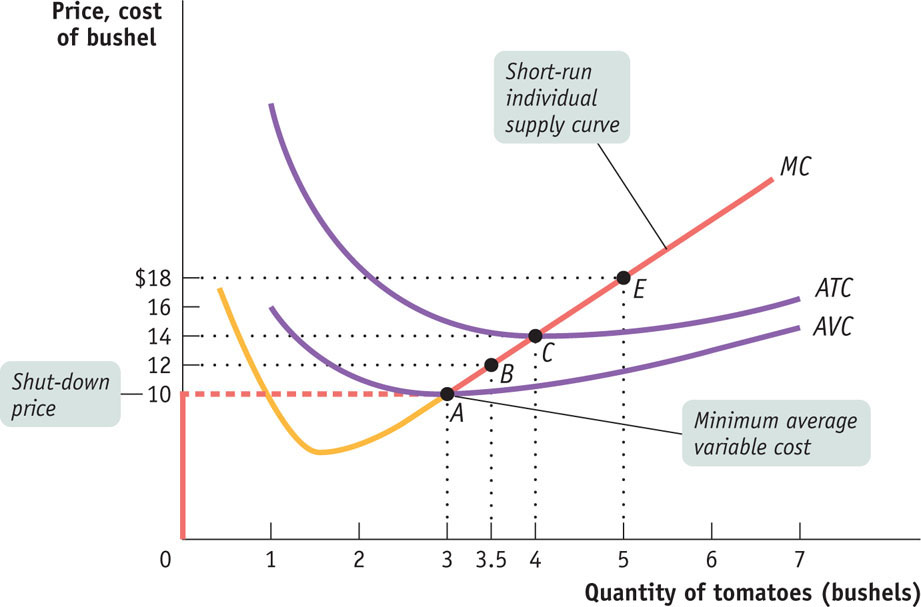

FIGURE27-1The Short-Run Individual Supply Curve

At a price below $10, no farms will produce. At a price of more than $10, each farm will produce the quantity of output at which its marginal cost is equal to the market price. As you can see from Figure 27-1, this will lead each farm to produce 4 bushels if the price is $14 per bushel, 5 bushels if the price is $18, and so on.

The short-

So if there are 100 organic tomato farms and the price of organic tomatoes is $18 per bushel, the industry as a whole will produce 500 bushels, corresponding to 100 farms × 5 bushels per farm. The result is the short-

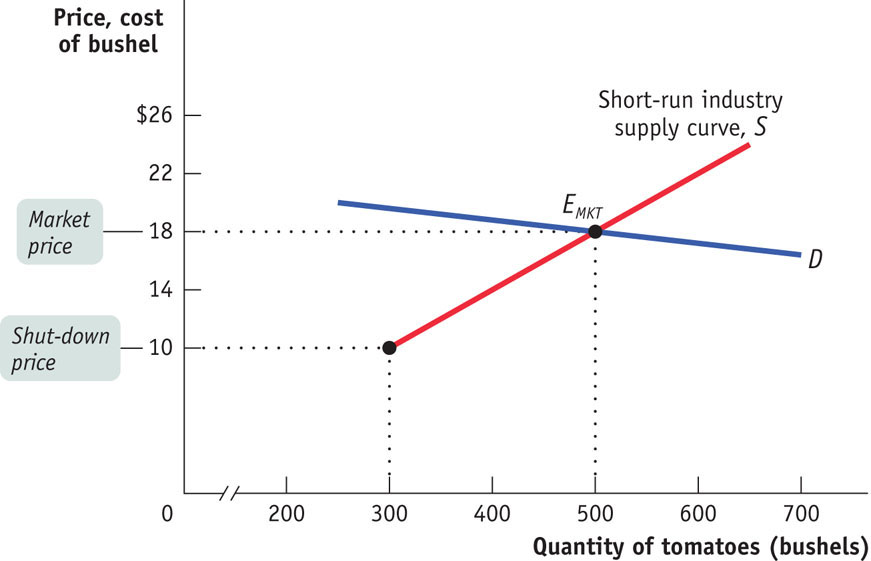

FIGURE27-2The Short-Run Market Equilibrium

There is a short-

The market demand curve, labeled D in Figure 27-2, crosses the short-

The Long-Run Industry Supply Curve

Suppose that in addition to the 100 farms currently in the organic tomato business, there are many other potential organic tomato farms. Suppose also that each of these potential farms would have the same cost curves as existing farms, like the one owned by Jennifer and Jason, upon entering the industry.

When will additional farms enter the industry? Whenever existing farms are making a profit—

What will happen as additional farms enter the industry? Clearly, the quantity supplied at any given price will increase. The short-

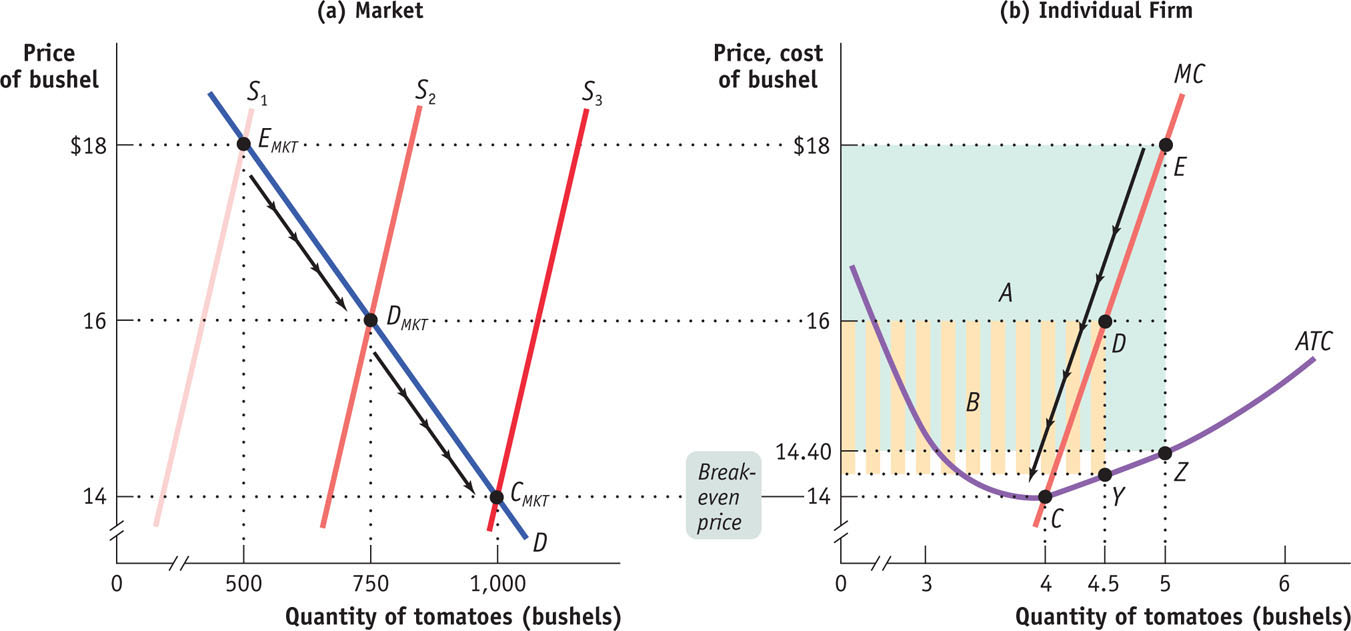

Figure 27-3 illustrates the effects of this chain of events on an existing farm and on the market; panel (a) shows how the market responds to entry, and panel (b) shows how an individual existing farm responds to entry. (Note that these two graphs have been rescaled in comparison to Figures 27-1 and 27-2 to better illustrate how profit changes in response to price.) In panel (a), S1 is the initial short-

FIGURE27-3The Long-Run Market Equilibrium

These profits will induce new producers to enter the industry, shifting the short-

Although diminished, the profit of existing farms at DMKT means that entry will continue and the number of farms will continue to rise. If the number of farms rises to 250, the short-

A market is in long-

Like EMKT and DMKT, CMKT is a short-

BALING IN, BAILING OUT

“King Cotton is back,” proclaimed a 2010 article in the Los Angeles Times, describing a cotton boom that had “turned great swaths of Central California a snowy white during harvest season.” Cotton prices were soaring: they more than tripled between early 2010 and early 2011. And farmers responded by planting more cotton.

What was behind the price rise? As we learned in Section 2, it was partly caused by temporary factors, notably severe floods in Pakistan that destroyed much of that nation’s cotton crop. But there was also a big rise in demand, especially from China, whose burgeoning textile and clothing industries demanded ever more raw cotton to weave into cloth. And all indications were that higher demand was here to stay.

So is cotton farming going to be a highly profitable business from now on? The answer is no, because when an industry becomes highly profitable, it draws in new producers, and that brings prices down. And the cotton industry was following the standard script.

For it wasn’t just the Central Valley of California that had turned “snowy white.” Farmers around the world were moving into cotton growing. “This summer, cotton will stretch from Queensland through northern NSW [New South Wales] all the way down to the Murrumbidgee valley in southern NSW,” declared an Australian report.

And by 2012, the entry of all these new producers had a big effect. By the summer of 2012, cotton prices were only about a third of their peak in early 2011. It was clear that the cotton boom had reached its limit—

To explore further the difference between short-

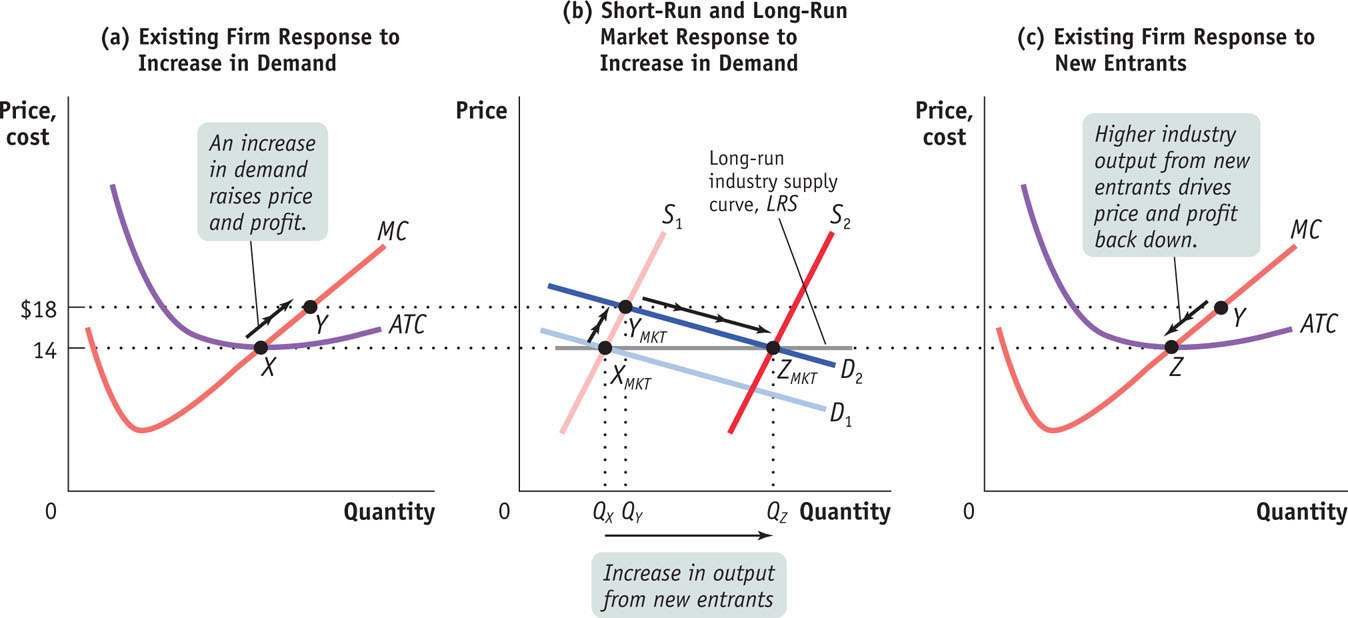

FIGURE27-4The Effect of an Increase in Demand in the Short Run and the Long Run

In panel (b) of Figure 27-4, D1 is the initial demand curve and S1 is the initial short-

Now suppose that the demand curve shifts out for some reason to D2. As shown in panel (b), in the short run, industry output moves along the short-

But we know that YMKT is not a long-

The effect of entry on an existing firm is illustrated in panel (c), in the movement from Y to Z along the firm’s individual supply curve. The firm reduces its output in response to the fall in the market price, ultimately arriving back at its original output quantity, corresponding to the minimum of its average total cost curve. In fact, every firm that is now in the industry—

The long-

The line LRS that passes through XMKT and ZMKT in panel (b) is the long-

In this particular case, the long-

In other industries, however, even the long-

Finally, it is possible for the long-

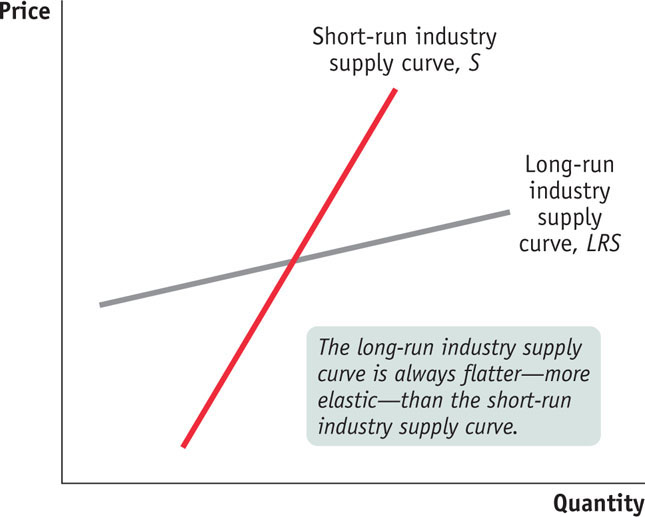

Regardless of whether the long-

FIGURE27-5Comparing the Short-Run and Long-Run Industry Supply Curves

The distinction between the short-

The Cost of Production and Efficiency in Long-Run Equilibrium

Our analysis leads us to three conclusions about the cost of production and efficiency in the long-

First, in a perfectly competitive industry in equilibrium, the value of marginal cost is the same for all firms. That’s because all firms produce the quantity of output at which marginal cost equals the market price, and as price-

Second, in a perfectly competitive industry with free entry and exit, each firm will have zero economic profit in the long-

The third and final conclusion is that the long-

So in the long-

27

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

1. Which of the following events will induce firms to enter an industry? Which will induce firms to exit? When will entry or exit cease? Explain your answer.

-

a. A technological advance lowers the fixed cost of production of every firm in the industry.

A fall in the fixed cost of production generates a fall in the average total cost of production and, in the short run, an increase in each firm’s profit at the current output level. So in the long run new firms will enter the industry. The increase in supply drives down price and profits. Once profits are driven back to zero, entry will cease. -

b. The wages paid to workers in the industry go up for an extended period of time.

An increase in wages generates an increase in the average variable and the average total cost of production at every output level. In the short run, firms incur losses at the current output level, and so in the long run some firms will exit the industry. (If the average variable cost rises sufficiently, some firms may even shut down in the short run.) As firms exit, supply decreases, price rises, and losses are reduced. Exit will cease once losses return to zero. -

c. A permanent change in consumer tastes increases demand for the good.

Price will rise as a result of the increased demand, leading to a short-run increase in profits at the current output level. In the long run, firms will enter the industry, generating an increase in supply, a fall in price, and a fall in profits. Once profits are driven back to zero, entry will cease. -

d. The price of a key input rises due to a long-

term shortage of that input. The shortage of a key input causes that input’s price to increase, resulting in an increase in average variable and average total cost for producers. Firms incur losses in the short run, and some firms will exit the industry in the long run. The fall in supply generates an increase in price and decreased losses. Exit will cease when the losses for remaining firms have returned to zero.

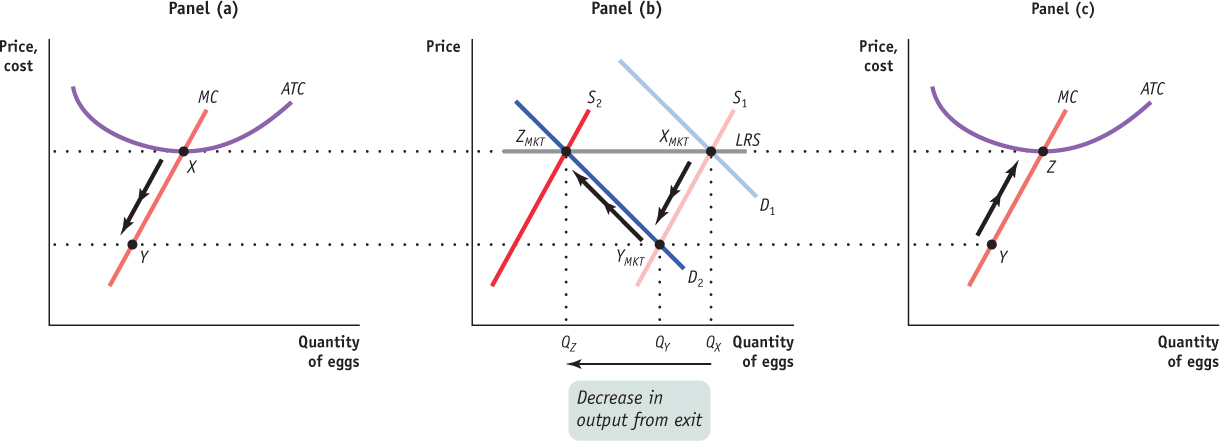

2. Assume that the egg industry is perfectly competitive and is in long-

Multiple-

Question

1. In the long run, a perfectly competitive firm will earn

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. With perfect competition, efficiency is generally attained in

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

3. Compared to the short-

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

4. Which of the following is generally true for perfect competition?

I. There is free entry and exit.

II. Long-

III. Firms maximize profits at the output level where P = MC.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

5. Which of the following will happen if perfectly competitive firms are earning positive economic profit?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

Draw correctly labeled side-