The Cost of Production and Efficiency in Long-Run Equilibrium

Our analysis leads us to three conclusions about the cost of production and efficiency in the long-

First, in a perfectly competitive industry in equilibrium, the value of marginal cost is the same for all firms. That’s because all firms produce the quantity of output at which marginal cost equals the market price, and as price-

Second, in a perfectly competitive industry with free entry and exit, each firm will have zero economic profit in long-

PITFALLS: ECONOMIC PROFIT, AGAIN

ECONOMIC PROFIT, AGAIN

Some readers may wonder why a firm would want to enter an industry if the market price is only slightly greater than the break-

The answer is that here, as always, when we calculate cost, we mean opportunity cost—that is, cost that includes the return a firm could get by using its resources elsewhere. And so the profit that we calculate is economic profit; if the market price is above the break-

The exception is an industry with increasing costs across the industry. Given a sufficiently high market price, early entrants make positive economic profits, but the last entrants do not as the market price falls. Costs are minimized for later entrants, as the industry reaches long-

The third and final conclusion is that the long-

So in the long-

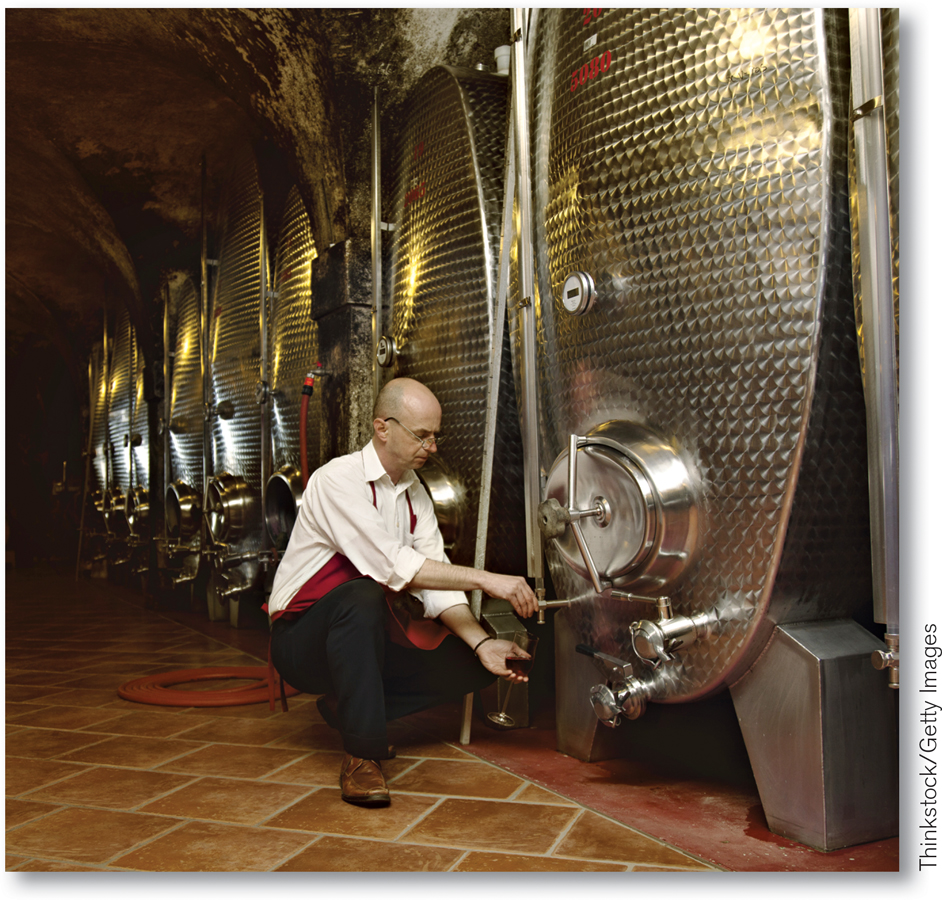

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: From Global Wine Glut to Shortage

From Global Wine Glut to Shortage

If you were a wine producer still in business in 2012, you were probably breathing a big sigh of relief. Why? Because that is when the global wine market went from glut to shortage. This was a big change from the years 2004 to 2010, when the wine industry battled with an oversupply of product and plunging prices, driven first by a series of large global harvests and then by declining demand due to the global recession of 2008. After years of losses, many wine producers finally decided to exit the industry.

By 2012, wine production capacity was down significantly in Europe, South America, Africa, and Australia, and inventories were at their lowest point in over a decade. Moreover, 2012 was a year of bad weather for wine producers. And that same year, American wine consumption started growing again, while China’s wine consumption was surging, quadrupling over the previous five years. So combine a significant drop in capacity, a weather-

But as industry analysts noted, many vintners are cheering. The lack of production in other parts of the world and surging demand in China have opened opportunities for expansion. As the CEO of Washington State’s Chateau Ste. Michelle winery, Ted Bessler, commented, “Right now, we have about 50,000 acres in the state. I can foresee that we could have as much as 150,000 or more.”

Hold onto your wine glasses—

Quick Review

The industry supply curve corresponds to the supply curve of earlier chapters. In the short run, the time period over which the number of producers is fixed, the short-

run market equilibrium is given by the intersection of the short-run industry supply curve and the demand curve. In the long run, the time period over which producers can enter or exit the industry, the long-run market equilibrium is given by the intersection of the long-run industry supply curve and the demand curve. In the long-run market equilibrium, no producer has an incentive to enter or exit the industry. The long-

run industry supply curve is often horizontal, although it may slope upward when a necessary input is in limited supply. It is always more elastic than the short- run industry supply curve. In the long-

run market equilibrium of a perfectly competitive industry, each firm produces at the same marginal cost, which is equal to the market price, and the total cost of production of the industry’s output is minimized. It is also efficient.

12-3

Question 12.4

Which of the following events will induce firms to enter an industry? Which will induce firms to exit? When will entry or exit cease? Explain your answer.

A technological advance lowers the fixed cost of production of every firm in the industry.

The wages paid to workers in the industry go up for an extended period of time.

A permanent change in consumer tastes increases demand for the good.

The price of a key input rises due to a long-

term shortage of that input.

Question 12.5

Assume that the egg industry is perfectly competitive and is in long-

run equilibrium with a perfectly elastic long- run industry supply curve. Health concerns about cholesterol then lead to a decrease in demand. Construct a figure similar to Figure 12-7, showing the short- run behavior of the industry and how long- run equilibrium is reestablished.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Shopping Apps, Showrooming, and the Challenges Facing Brick-and-Mortar Retailers

In a Sunnyvale, California Best Buy, Tri Trang found the perfect gift for his girlfriend, a $184.85 Garmin GPS. Before mobile shopping apps appeared, he would have purchased it there. Instead, Trang whipped out his smartphone to do a price comparison. Finding the same item on Amazon.com for $106.75 with free shipping, he bought it from Amazon on the spot.

For brick-

Before shopping apps, a traditional retailer could lure customers into its store with enticing specials and reasonably expect them to buy more profitable items with prompting from a salesperson. But those days are fast disappearing. The consulting firm Accenture found that 73% of customers with mobile devices preferred to shop with their phones rather than talk to a salesperson. In just four years, from 2010 to 2014, the use of mobile coupons has quadrupled from 12.3 million to 53.2 million.

But brick-

However, traditional retailers know that their survival rests on pricing. While prices on their websites tend to be lower than in the stores, these retailers are still struggling to compete with online sellers like Amazon.com. A recent study showed Amazon.com’s prices were about 9% lower than Walmart.com’s and 14% lower than Target.com’s. Best Buys now offers to match online prices for its best customers.

It’s clearly a race for survival. As one analyst said, “Only a couple of retailers can play the lowest-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 12.6

From the evidence in the case, what can you infer about whether or not the retail market for electronics satisfied the conditions for perfect competition before the advent of mobile-

device comparison price shopping? What was the most important impediment to competition? From the evidence in the case, what can you infer about whether or not the retail market for electronics satisfied the conditions for perfect competition before the advent of mobile-device comparison price shopping? What was the most important impediment to competition? Question 12.7

What effect is the introduction of mobile shopping apps having on competition in the retail market for electronics? On the profitability of brick-

and- mortar retailers like Best Buy? What, on average, will be the effect on the consumer surplus of purchasers of these items? What effect is the introduction of mobile shopping apps having on competition in the retail market for electronics? On the profitability of brick-and- mortar retailers like Best Buy? What, on average, will be the effect on the consumer surplus of purchasers of these items? Question 12.8

Why are some retailers responding by having manufacturers make exclusive versions of products for them? Is this trend likely to increase or diminish?

Why are some retailers responding by having manufacturers make exclusive versions of products for them? Is this trend likely to increase or diminish?