Welfare Effects of Monopoly

By restricting output below the level at which marginal cost is equal to the market price, a monopolist increases its profit but hurts consumers. To assess whether this is a net benefit or loss to society, we must compare the monopolist’s gain in profit to the loss in consumer surplus. And what we learn is that the loss in consumer surplus is larger than the monopolist’s gain. Monopoly causes a net loss for society.

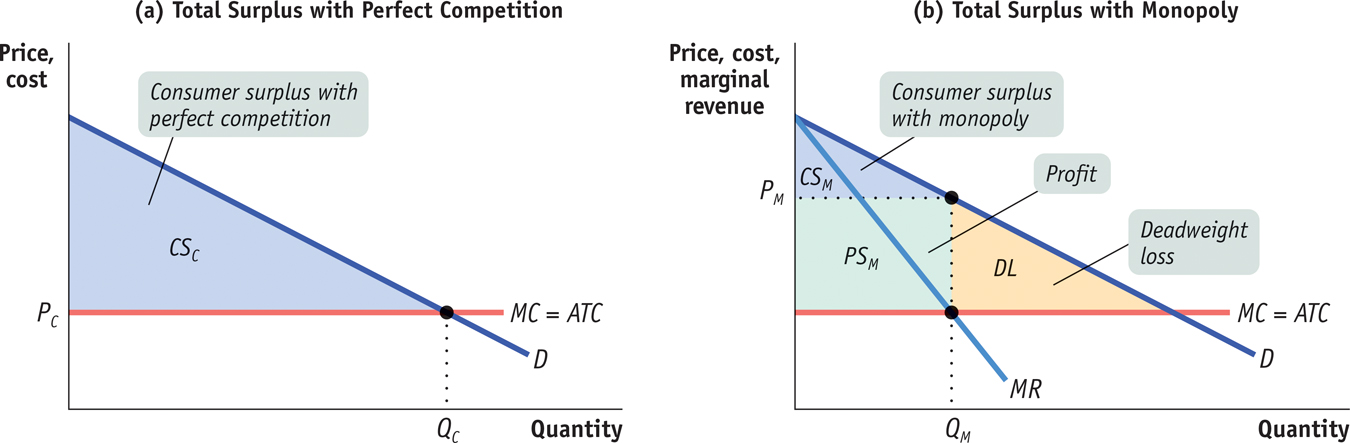

To see why, let’s return to the case where the marginal cost curve is horizontal, as shown in the two panels of Figure 13-8. Here the marginal cost curve is MC, the demand curve is D, and, in panel (b), the marginal revenue curve is MR.

13-8

Monopoly Causes Inefficiency

Panel (a) shows what happens if this industry is perfectly competitive. Equilibrium output is QC; the price of the good, PC, is equal to marginal cost, and marginal cost is also equal to average total cost because there is no fixed cost and marginal cost is constant. Each firm is earning exactly its average total cost per unit of output, so there is no profit and no producer surplus in this equilibrium.

The consumer surplus generated by the market is equal to the area of the blue-

Panel (b) shows the results for the same market, but this time assuming that the industry is a monopoly. The monopolist produces the level of output QM, at which marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue, and it charges the price PM. The industry now earns profit—

By comparing panels (a) and (b), we see that in addition to the redistribution of surplus from consumers to the monopolist, another important change has occurred: the sum of profit and consumer surplus—

This net loss arises because some mutually beneficial transactions do not occur. There are people for whom an additional unit of the good is worth more than the marginal cost of producing it but who don’t consume it because they are not willing to pay PM.

If you recall our discussion of the deadweight loss from taxes you will notice that the deadweight loss from monopoly looks quite similar. Indeed, by driving a wedge between price and marginal cost, monopoly acts much like a tax on consumers and produces the same kind of inefficiency.

So monopoly hurts the welfare of society as a whole and is a source of market failure. Is there anything government policy can do about it?