Perfect Price Discrimination

Let’s return to the example of business travelers and students traveling between Bismarck and Ft. Lauderdale, illustrated in Figure 13-11, and ask what would happen if the airline could distinguish between the two groups of customers in order to charge each a different price.

Clearly, the airline would charge each group its willingness to pay—

Perfect price discrimination takes place when a monopolist charges each consumer his or her willingness to pay—

In this case, the consumers do not get any consumer surplus! The entire surplus is captured by the monopolist in the form of profit. When a monopolist is able to capture the entire surplus in this way, we say that it achieves perfect price discrimination.

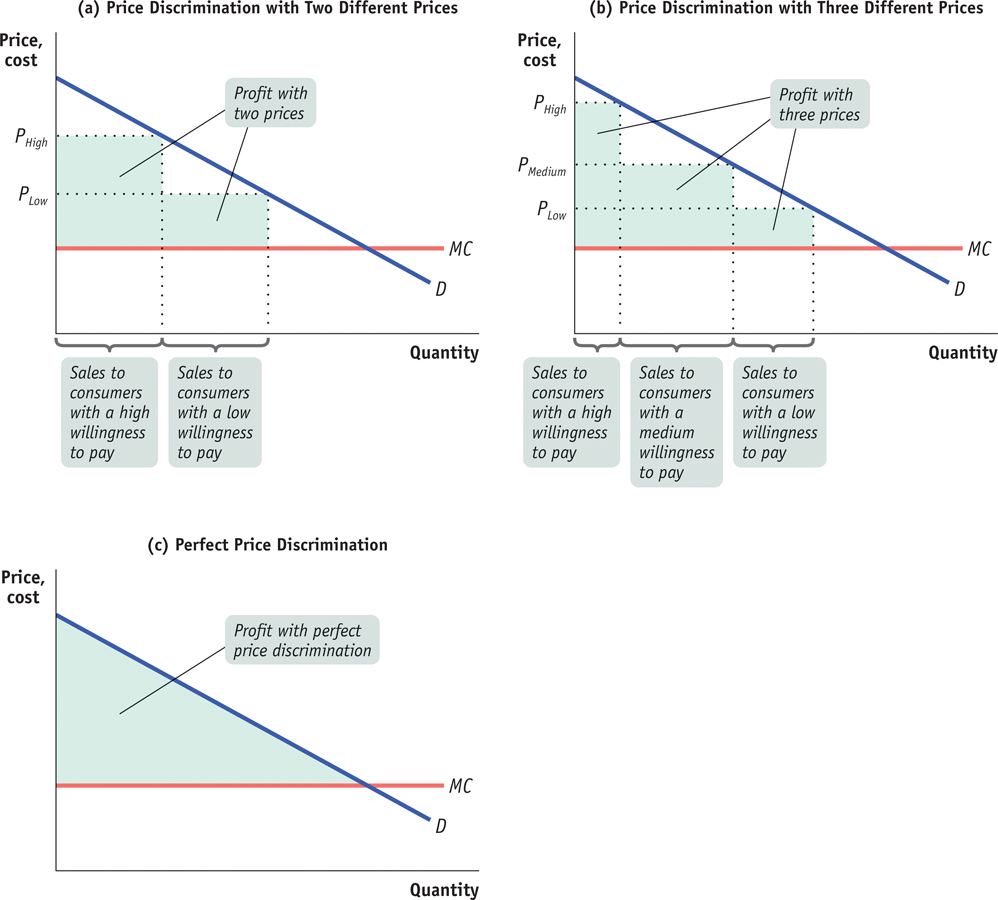

In general, the greater the number of different prices a monopolist is able to charge, the closer it can get to perfect price discrimination. Figure 13-12 shows a monopolist facing a downward-

13-12

Price Discrimination

In panel (a) the monopolist charges two different prices; in panel (b) the monopolist charges three different prices. Two things are apparent:

The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the lower the lowest price—

that is, some consumers will pay prices that approach marginal cost. The greater the number of prices the monopolist charges, the more money it extracts from consumers.

With a very large number of different prices, the picture would look like panel (c), a case of perfect price discrimination. Here, consumers least willing to buy the good pay marginal cost, and the entire consumer surplus is extracted as profit.

Both our airline example and the example in Figure 13-12 can be used to make another point: a monopolist that can engage in perfect price discrimination doesn’t cause any inefficiency! The reason is that the source of inefficiency is eliminated: all potential consumers who are willing to purchase the good at a price equal to or above marginal cost are able to do so. The perfectly price-

Perfect price discrimination is almost never possible in practice. At a fundamental level, the inability to achieve perfect price discrimination is a problem of prices as economic signals, a phenomenon we noted in Chapter 4.

When prices work as economic signals, they convey the information needed to ensure that all mutually beneficial transactions will indeed occur: the market price signals the seller’s cost, and a consumer signals willingness to pay by purchasing the good whenever that willingness to pay is at least as high as the market price.

The problem in reality, however, is that prices are often not perfect signals: a consumer’s true willingness to pay can be disguised, as by a business traveler who claims to be a student when buying a ticket in order to obtain a lower fare. When such disguises work, a monopolist cannot achieve perfect price discrimination.

However, monopolists do try to move in the direction of perfect price discrimination through a variety of pricing strategies. Common techniques for price discrimination include the following:

Advance purchase restrictions. Prices are lower for those who purchase well in advance (or in some cases for those who purchase at the last minute). This separates those who are likely to shop for better prices from those who won’t.

Volume discounts. Often the price is lower if you buy a large quantity. For a consumer who plans to consume a lot of a good, the cost of the last unit—

the marginal cost to the consumer— is considerably less than the average price. This separates those who plan to buy a lot and so are likely to be more sensitive to price from those who don’t. Two-

part tariffs . With a two-part tariff, a customer pays a flat fee up- front and then a per- unit fee on each item purchased. So in a discount club like Sam’s Club (which is not a monopolist but a monopolistic competitor), you pay an annual fee in addition to the cost of the items you purchase. So the cost of the first item you buy is in effect much higher than that of subsequent items, making the two- part tariff behave like a volume discount.

Our discussion also helps explain why government policies on monopoly typically focus on preventing deadweight losses, not preventing price discrimination—

If sales to consumers formerly priced out of the market but now able to purchase the good at a lower price generate enough surplus to offset the loss in surplus to those now facing a higher price and no longer buying the good, then total surplus increases when price discrimination is introduced.

An example of this might be a drug that is disproportionately prescribed to senior citizens, who are often on fixed incomes and so are very sensitive to price. A policy that allows a drug company to charge senior citizens a low price and everyone else a high price may indeed increase total surplus compared to a situation in which everyone is charged the same price. But price discrimination that creates serious concerns about equity is likely to be prohibited—

ECONOMICS in Action: Sales, Factory Outlets, and Ghost Cities

Sales, Factory Outlets, and Ghost Cities

Have you ever wondered why department stores occasionally hold sales, offering their merchandise for considerably less than the usual prices? Or why, driving along America’s highways, you sometimes encounter clusters of “factory outlet” stores a few hours away from the nearest city?

These familiar features of the economic landscape are actually rather peculiar if you think about them: why should sheets and towels be suddenly cheaper for a week each winter, or raincoats be offered for less in Freeport, Maine, than in Boston? In each case the answer is that the sellers—

Why hold regular sales of sheets and towels? Stores are aware that some consumers buy these goods only when they discover that they need them; they are not likely to put a lot of effort into searching for the best price and so have a relatively low price elasticity of demand. So the store wants to charge high prices for customers who come in on an ordinary day.

But shoppers who plan ahead, looking for the lowest price, will wait until there is a sale. By scheduling such sales only now and then, the store is in effect able to price-

An outlet store serves the same purpose: by offering merchandise for low prices, but only at a considerable distance away, a seller is able to establish a separate market for those customers who are willing to make the effort to search out lower prices—

Finally, let’s return to airline tickets to mention one of the truly odd features of their prices. Often a flight from one major destination to another—

But often there is a flight between two major destinations that makes a stop along the way—

So why don’t passengers simply buy a ticket from Chicago to Los Angeles, but get off at Salt Lake City? Well, some do—

Quick Review

Not every monopolist is a single-

price monopolist . Many monopolists, as well as oligopolists and monopolistic competitors, engage in price discrimination.Price discrimination is profitable when consumers differ in their sensitivity to the price. A monopolist charges higher prices to low-

elasticity consumers and lower prices to high- elasticity ones. A monopolist able to charge each consumer his or her willingness to pay for the good achieves perfect price discrimination and does not cause inefficiency because all mutually beneficial transactions are exploited.

13-4

Question 13.9

True or false? Explain your answer.

A single-

price monopolist sells to some customers that a price- discriminating monopolist refuses to. A price-

discriminating monopolist creates more inefficiency than a single- price monopolist because it captures more of the consumer surplus. Under price discrimination, a customer with highly elastic demand will pay a lower price than a customer with inelastic demand.

Question 13.10

Which of the following are cases of price discrimination and which are not? In the cases of price discrimination, identify the consumers with high and those with low price elasticity of demand.

Damaged merchandise is marked down.

Restaurants have senior citizen discounts.

Food manufacturers place discount coupons for their merchandise in newspapers.

Airline tickets cost more during the summer peak flying season.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Amazon and Hachette Go to War

In May 2014, all-

All publishers pay retailers a share of sales prices. What set off hostilities in this case was Amazon’s demand that Hachette raise Amazon’s share from 30 to 50%. This was a familiar story: Amazon has demanded ever-

Amazon claimed that the publisher could pay more out of its profit margin—

Meanwhile, Amazon had other problems: in July 2014 it announced that it lost $800 million in the previous quarter because profits from sales were not paying for its vast warehouse and delivery system. In its 20 years of existence Amazon has never made a profit, and investors were growing impatient. As one industry analyst commented, “Skepticism is increasing. It’s hard to have $20 billion in revenue and not make any money. It’s a real feat.”

As this book went to press, Amazon was in a public relations battle with Authors United, a group of over 900 best-

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 13.11

What is the source of surplus in this industry? Who generates it? How is it divided among the various agents (author, publisher, and retailer)?

What is the source of surplus in this industry? Who generates it? How is it divided among the various agents (author, publisher, and retailer)?Question 13.12

What are the various sources of market power here? What is at risk for the various parties?

What are the various sources of market power here? What is at risk for the various parties?