Overcoming the Prisoners’ Dilemma: Repeated Interaction and Tacit Collusion

A firm engages in strategic behavior when it attempts to influence the future behavior of other firms.

Thelma and Louise in their cells are playing what is known as a one-

Suppose that ADM and Ajinomoto expect to be in the lysine business for many years and therefore expect to play the game of cheat versus collude shown in Figure 14-1 many times. Would they really betray each other time and again?

A strategy of tit for tat involves playing cooperatively at first, then doing whatever the other player did in the previous period.

Probably not. Suppose that ADM considers two strategies. In one strategy it always cheats, producing 40 million pounds of lysine each year, regardless of what Ajinomoto does. In the other strategy, it starts with good behavior, producing only 30 million pounds in the first year, and watches to see what its rival does. If Ajinomoto also keeps its production down, ADM will stay cooperative, producing 30 million pounds again for the next year. But if Ajinomoto produces 40 million pounds, ADM will take the gloves off and also produce 40 million pounds the next year. This latter strategy—

Tit for tat is a form of strategic behavior, which we have just defined as behavior intended to influence the future actions of other players. Tit for tat offers a reward to the other player for cooperative behavior—

The payoff to ADM of each of these strategies would depend on which strategy Ajinomoto chooses. Consider the four possibilities, shown in Figure 14-3:

14-3

How Repeated Interaction Can Support Collusion

If ADM plays tit for tat and so does Ajinomoto, both firms will make a profit of $180 million each year.

If ADM plays always cheat but Ajinomoto plays tit for tat, ADM makes a profit of $200 million the first year but only $160 million per year thereafter.

If ADM plays tit for tat but Ajinomoto plays always cheat, ADM makes a profit of only $150 million in the first year but $160 million per year thereafter.

If ADM plays always cheat and Ajinomoto does the same, both firms will make a profit of $160 million each year.

Which strategy is better? In the first year, ADM does better playing always cheat, whatever its rival’s strategy: it assures itself that it will get either $200 million or $160 million (which of the two payoffs it actually receives depends on whether Ajinomoto plays tit for tat or always cheat). This is better than what it would get in the first year if it played tit for tat: either $180 million or $150 million. But by the second year, a strategy of always cheat gains ADM only $160 million per year for the second and all subsequent years, regardless of Ajinomoto’s actions.

Over time, the total amount gained by ADM by playing always cheat is less than the amount it would gain by playing tit for tat: for the second and all subsequent years, it would never get any less than $160 million and would get as much as $180 million if Ajinomoto played tit for tat as well. Which strategy, always cheat or tit for tat, is more profitable depends on two things: how many years ADM expects to play the game and what strategy its rival follows.

If ADM expects the lysine business to end in the near future, it is in effect playing a one-

But if ADM expects to be in the business for a long time and thinks Ajinomoto is likely to play tit for tat, it will make more profits over the long run by playing tit for tat, too. It could have made some extra short-

When firms limit production and raise prices in a way that raises one anothers’ profits, even though they have not made any formal agreement, they are engaged in tacit collusion.

The lesson of this story is that when oligopolists expect to compete with one another over an extended period of time, each individual firm will often conclude that it is in its own best interest to be helpful to the other firms in the industry. So it will restrict its output in a way that raises the profits of the other firms, expecting them to return the favor. Despite the fact that firms have no way of making an enforceable agreement to limit output and raise prices (and are in legal jeopardy if they even discuss prices), they manage to act “as if” they had such an agreement. When this happens, we say that firms engage in tacit collusion.

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The Rise and Fall and Rise of OPEC

The Rise and Fall and Rise of OPEC

Call it the cartel that does not need to meet in secret. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, usually referred to as OPEC, includes 12 national governments (Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela), and it controls 40% of the world’s oil exports and 80% of its proven reserves. Two other oil-

Unlike corporations, which are often legally prohibited by governments from reaching agreements about production and prices, national governments can talk about whatever they feel like. OPEC members routinely meet to try to set targets for production.

These nations are not particularly friendly with one another. Indeed, OPEC members Iraq and Iran fought a spectacularly bloody war with each other in the 1980s. And, in 1990, Iraq invaded another member, Kuwait. (A mainly American force based in yet another OPEC member, Saudi Arabia, drove the Iraqis out of Kuwait.)

Yet the members of OPEC are effectively players in a game with repeated interactions. In any given year it is in their combined interest to keep output low and prices high. But it is also in the interest of any one producer to cheat and produce more than the agreed-

So how successful is the cartel? Well, it’s had its ups and downs. Analysts have estimated that of 12 announced quota reductions, OPEC was able to successfully defend its price floor 80% of the time.

14-4

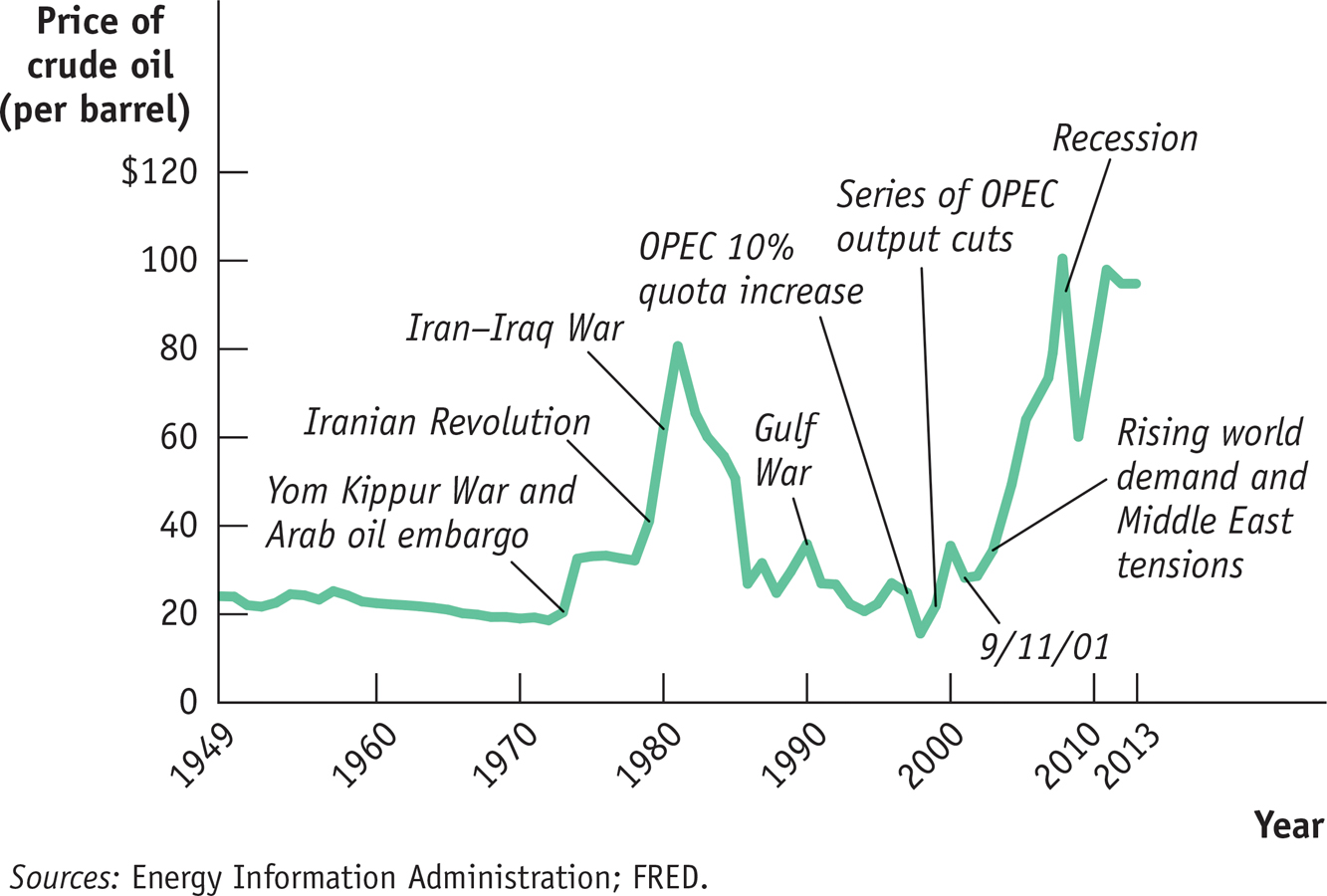

Crude Oil Prices, 1949-

Figure 14-4 shows the price of oil in constant dollars (that is, the value of a barrel of oil in terms of other goods) since 1949. OPEC first demonstrated its muscle in 1974: in the aftermath of a war in the Middle East, several OPEC producers limited their output—

By the mid-

The cartel started acting effectively at the end of the 1990s, thanks largely to the efforts of Mexico’s oil minister, who orchestrated output reductions, and Saudi Arabia’s assumption of the role of “swing producer.” As the key decision maker and the largest OPEC producer by far, Saudi Arabia allowed other members to produce as much as they could, and then adjusted its own output to meet the overall limit, thereby easing friction among members. These actions helped raise the price of oil from less than $10 per barrel in 1998 to a range of $20 to $30 per barrel in 2003.

Since 2008, OPEC has experienced the steepest roller-

More recently, as Iraq and Iran have signaled their intention to raise output, as the United States produces increasing amounts of oil from its shale formations, and as oil production from Brazil and Canada increases, some OPEC watchers are predicting that the cartel’s future cohesion may very well be in jeopardy.

Quick Review

Economists use game theory to study firms’ behavior when there is interdependence between their payoffs. The game can be represented with a payoff matrix. Depending on the payoffs, a player may or may not have a dominant strategy.

When each firm has an incentive to cheat, but both are worse off if both cheat, the situation is known as a prisoners’ dilemma.

Players who don’t take their interdependence into account arrive at a Nash, or noncooperative, equilibrium. But if a game is played repeatedly, players may engage in strategic behavior, sacrificing short-

run profit to influence future behavior. In repeated prisoners’ dilemma games, tit for tat is often a good strategy, leading to successful tacit collusion.

14-3

Question 14.4

Find the Nash (noncooperative) equilibrium actions for the following payoff matrix. Which actions maximize the total payoff of Nikita and Margaret? Why is it unlikely that they will choose those actions without some communication?

Question 14.5

Which of the following factors make it more likely that oligopolists will play noncooperatively? Which make it more likely that they will engage in tacit collusion? Explain.

Each oligopolist expects several new firms to enter the market in the future.

It is very difficult for a firm to detect whether another firm has raised output.

The firms have coexisted while maintaining high prices for a long time.

Solutions appear at back of book.