How Much of a Public Good Should Be Provided?

In some cases, provision of a public good is an “either-

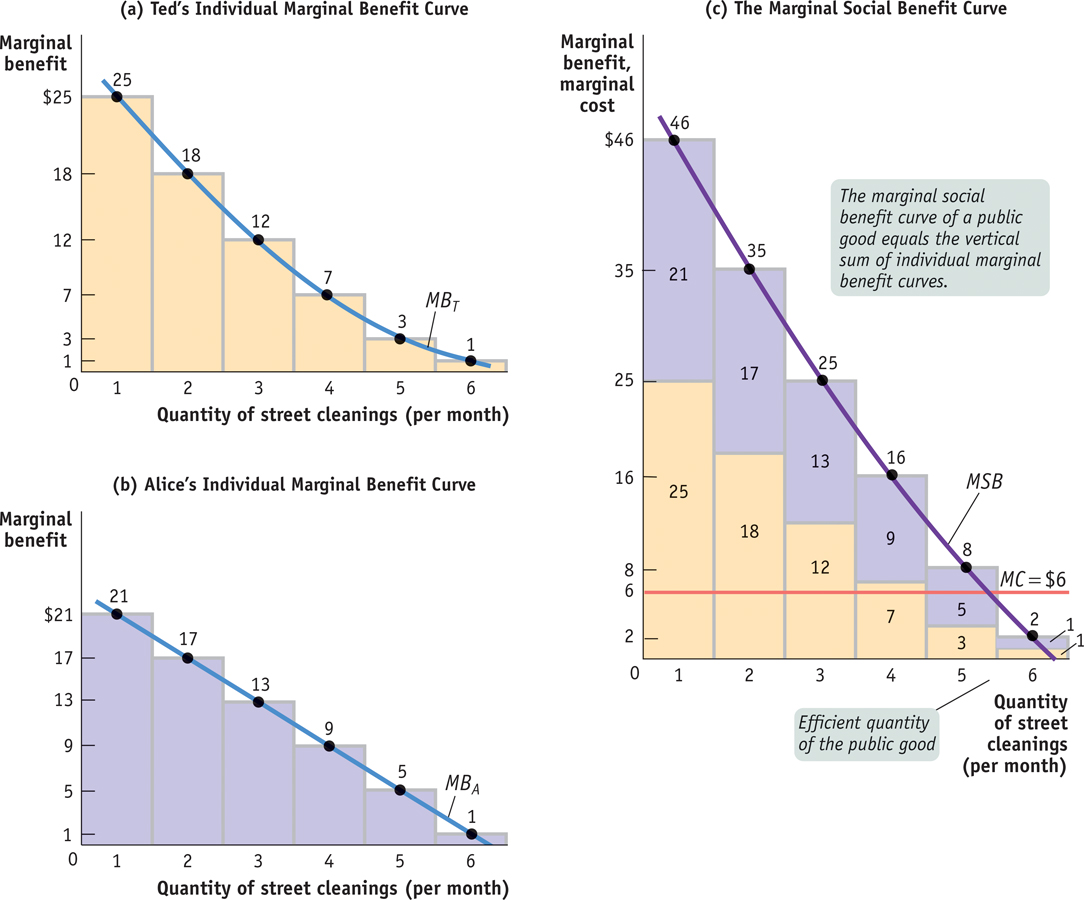

Imagine a city in which there are only two residents, Ted and Alice. Assume that the public good in question is street cleaning and that Ted and Alice truthfully tell the government how much they value a unit of the public good, where a unit is equal to one street cleaning per month. Specifically, each of them tells the government his or her willingness to pay for another unit of the public good supplied—an amount that corresponds to that individual’s marginal benefit of another unit of the public good.

Using this information plus information on the cost of providing the good, the government can use marginal analysis to find the efficient level of providing the public good: the level at which the marginal social benefit of the public good is equal to the marginal cost of producing it. Recall from Chapter 16 that the marginal social benefit of a good is the benefit that accrues to society as a whole from the consumption of one additional unit of the good.

But what is the marginal social benefit of another unit of a public good—

Why? Because a public good is nonrival in consumption—

Figure 17-2 illustrates the efficient provision of a public good, showing three marginal benefit curves. Panel (a) shows Ted’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBT: he would be willing to pay $25 for the city to clean its streets once a month, an additional $18 to have it done a second time, and so on. Panel (b) shows Alice’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBA. Panel (c) shows the marginal social benefit curve from street cleaning, MSB: it is the vertical sum of Ted’s and Alice’s individual marginal benefit curves, MBT and MBA.

17-2

A Public Good

Voting as a Public Good

It’s a sad fact that many Americans who are eligible to vote don’t bother to. As a result, their interests tend to be ignored by politicians. But what’s even sadder is that this self-

As the economist Mancur Olson pointed out in a famous book titled The Logic of Collective Action, voting is a public good, one that suffers from severe free-

Imagine that you are one of a million people who would stand to gain the equivalent of $100 each if some plan is passed in a statewide referendum—

Of course, many people do vote out of a sense of civic duty. But because political action is a public good, in general people devote too little effort to defending their own interests.

The result, Olson pointed out, is that when a large group of people share a common political interest, they are likely to exert too little effort promoting their cause and so will be ignored. Conversely, small, well-

Is this a reason to distrust democracy? Winston Churchill said it best: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the other forms that have been tried.”

To maximize society’s welfare, the government should clean the street up to the level at which the marginal social benefit of an additional cleaning is no longer greater than the marginal cost. Suppose that the marginal cost of street cleaning is $6 per cleaning. Then the city should clean its streets 5 times per month, because the marginal social benefit of going from 4 to 5 cleanings is $8, but going from 5 to 6 cleanings would yield a marginal social benefit of only $2.

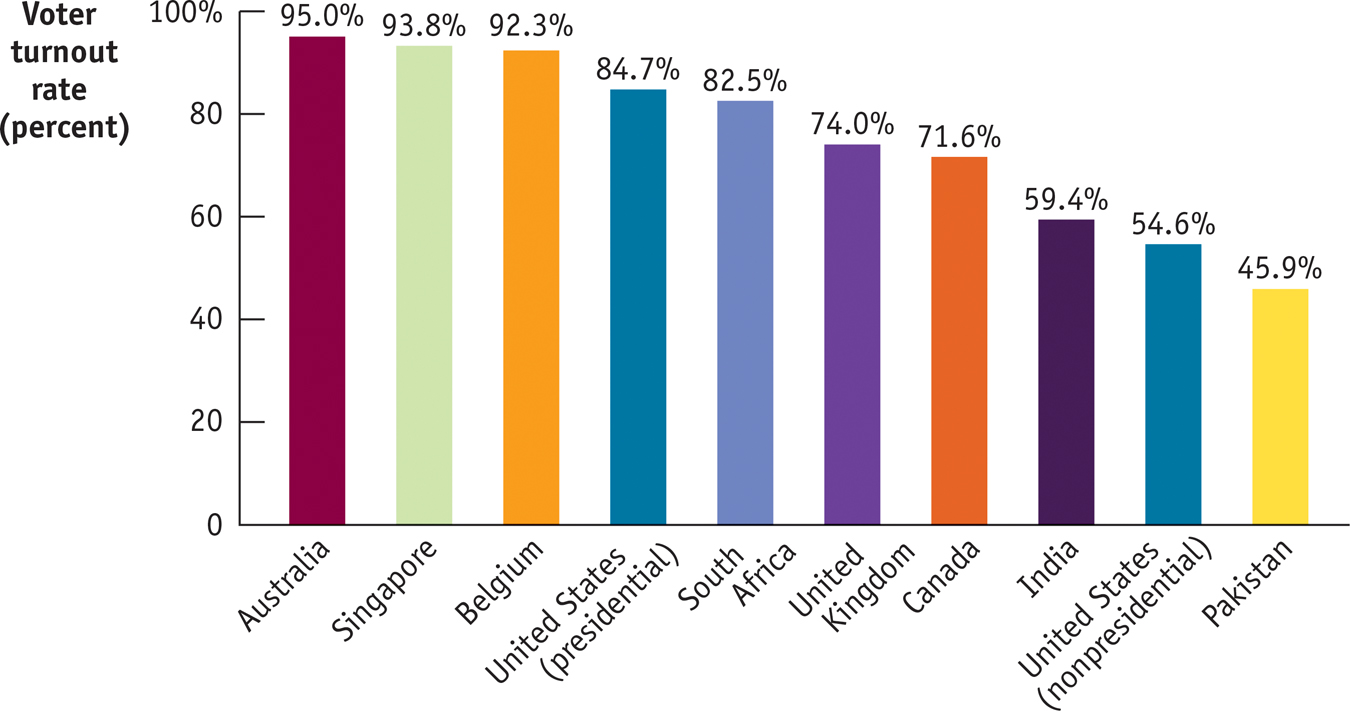

| Voting as a Public Good: The Global Perspective |

Despite the fact that it can be an entirely rational choice not to vote, many countries consistently achieve astonishingly high turnout rates in their elections by adopting policies that encourage voting. In Belgium, Singapore, and Australia, voting is compulsory; eligible voters are penalized if they fail to do their civic duty by casting their ballots. These penalties are effective at getting out the vote. When Venezuela dropped its mandatory voting requirement, the turnout rate dropped 30%; when the Netherlands did the same, there was a 20% drop-

Other countries have policies that reduce the cost of voting; for example, declaring election day a work holiday (giving citizens ample time to cast their ballots), allowing voter registration on election day (eliminating the need for advance planning), and permitting voting by mail (increasing convenience).

This figure shows turnout rates in several countries, measured as the percentage of eligible voters who cast ballots, averaged over elections held between 1945 and 2013. As you can see, Australia, Singapore, and Belgium have the highest voter turnout rates. The United States has a relatively high voter turnout during presidential elections. However, turnout drops significantly in nonpresidential elections, when the United States has the lowest turnout rate among advanced countries. In general, the past four decades have seen a decline in voter turnout rates in the major democracies, most dramatically among the youngest voters.

Source: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

Figure 17-2 can help reinforce our understanding of why we cannot rely on individual self-

The point is that the marginal social benefit of one more unit of a public good is always greater than the individual marginal benefit to any one individual. That is why no individual is willing to pay for the efficient quantity of the good.

Does this description of the public-

In the case of a public good, the individual marginal benefit of a consumer plays the same role as the price received by the producer in the case of positive externalities: both cases create insufficient incentive to provide an efficient amount of the good.

The problem of providing public goods is very similar to the problem of dealing with positive externalities; in both cases there is a market failure that calls for government intervention. One basic rationale for the existence of government is that it provides a way for citizens to tax themselves in order to provide public goods—

Of course, if society really consisted of only two individuals, they would probably manage to strike a deal to provide the good. But imagine a city with a million residents, each of whose individual marginal benefit from provision of the good is only a tiny fraction of the marginal social benefit. It would be impossible for people to reach a voluntary agreement to pay for the efficient level of street cleaning—