The Affordable Care Act

However one rates the past performance of the U.S. health care system, by 2009 it was clearly in trouble, on two fronts.

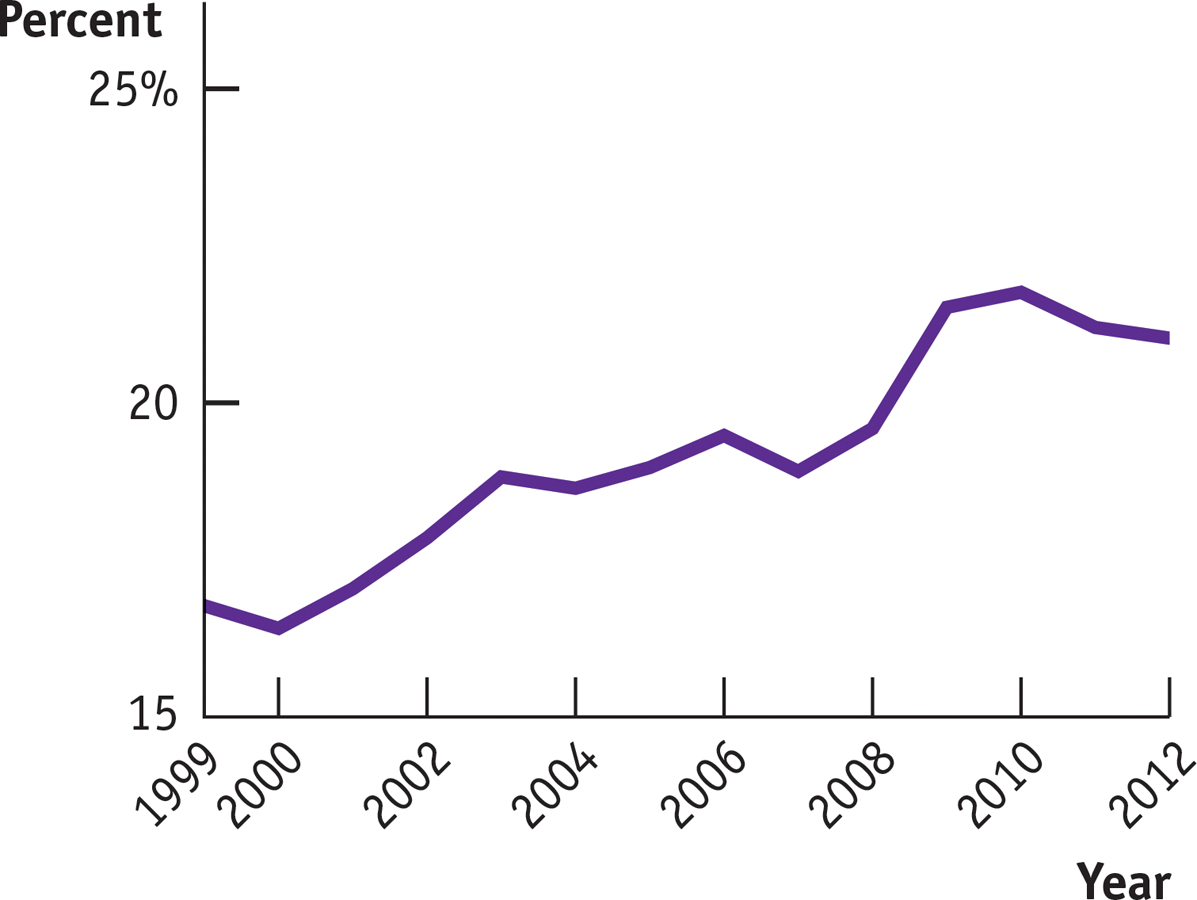

First, a growing number of working-

18-7

Uninsured Working-

Lying behind the growing number of uninsured, in turn, were sharply rising premiums for health insurance, reflecting rapid growth in overall health care costs. Figure 18-8 shows overall U.S. spending on health care as a percentage of GDP, a measure of the nation’s total income, since the 1960s. As you can see, health spending has tripled as a share of income since 1965; this increase in spending explains why health insurance has become more expensive. Similar trends can be observed in other countries.

18-8

Rising Health Care Costs, 1960-

Why was health spending rising? The consensus of health experts is that it’s a result of medical progress. As medical science progresses, conditions that could not be treated in the past become treatable—

The combination of a rising number of uninsured and rising costs led to many calls for health care reform in the United States. And so in 2010 Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which took full effect in 2014. It was the largest expansion of the American welfare state since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. It had two major objectives: covering the uninsured and cost control. Let’s look at each in turn.

Covering the Uninsured On the coverage side, the ACA closely follows a model that has been successfully used in Massachusetts since 2006 (introduced under Republican governor at the time, Mitt Romney). To understand the logic of both the Massachusetts plan and the ACA, consider the problem facing one major category of uninsured Americans: the many people who seek coverage in the individual insurance market but are turned down because they have preexisting medical conditions, which insurance companies fear could lead to large future expenses. (Insurance companies were known to deny coverage for even minor ailments, like allergies or a rash you had in college.) How could insurance be made available to such people?

One answer would be regulations requiring that insurance companies offer the same policies to everyone, regardless of medical history—

To make community rating work, it’s necessary to supplement it with other policies. Both the Massachusetts reform and the ACA add two key features. First is the requirement that everyone purchase health insurance—

It’s important to realize that this system is like a three-

Will this arrangement, once fully implemented, succeed in covering more or less everyone? The Massachusetts precedent is encouraging on that front: by 2012, more than 96% of the state’s residents had health insurance and virtually all children were covered. Since the ACA is very similar in structure, it ought to produce similar results.

Cost Control But will the ACA control costs? In itself, the expansion of coverage will raise health care spending, although not by as much as you might think. The uninsured are by and large relatively young, and the young have relatively low health care costs. (The elderly are already covered by Medicare.) The question is whether the reform can succeed in “bending the curve”—reducing the rate of growth of health costs over time.

The ACA’s promise to control costs starts from the premise that the U.S. medical system, as currently constituted, has skewed incentives that waste resources. Because most care is paid for by insurance, neither doctors nor patients have an incentive to worry about costs. In fact, because health care providers are generally paid for each procedure they perform, there’s a financial incentive to provide additional care—

The bill attempts to correct these skewed incentives in a variety of ways, from stricter oversight of reimbursements, to linking payments to a procedure’s medical value, to paying health care providers for improved health outcomes rather than the number of procedures, and by limiting the tax deductibility of employment-

The ACA’s launch As you might gather, the ACA sets up an insurance system considerably more complex than other government programs like Medicare and Medicaid, which simply provide insurance directly. The ACA sets up special online marketplaces, the “exchanges,” in which insurance companies offer policies from which individuals must choose. To figure out how much these policies really cost, it’s necessary to calculate the subsidy you receive, which depends on your income as well as the premium. Making all of that work is a difficult programming problem. And sure enough, when healthcare.gov, the federally run online exchange, started up in October 2013, the system crashed repeatedly. For the next two months few people managed to sign up.

This was, however, a problem with the software, not the fundamental structure of the law, and by the beginning of 2014 it was largely solved. There was a huge surge of people signing up as the deadline for 2014 coverage approached, and by the time that deadline arrived more than 8 million people had signed up via the exchanges, while millions more had either purchased directly from insurers or been covered by an expansion of Medicaid.

How many of those signing up were newly insured? At first there were warnings that many of the policies being bought through the exchanges might simply be replacing existing coverage. By the summer of 2014, however, multiple independent surveys showed a sharp drop in the percentage of respondents without insurance. At this point it seems likely that the ACA will, indeed, manage to cover many though not all uninsured Americans. Whether it will also succeed in reducing the rate of cost growth remains to be seen, although by 2014 there were early signs that the rate of growth of health care costs was indeed falling.

ECONOMICS in Action: What Medicaid Does

What Medicaid Does

Do social insurance programs actually help their beneficiaries? The answer isn’t always as obvious as you might think. Take the example of Medicaid, which provides health insurance to low-

Testing such assertions is tricky. You can’t just compare people who are on Medicaid with people who aren’t, since the program’s beneficiaries differ in many ways from those who aren’t on the program. And we don’t normally get to do controlled experiments in which otherwise comparable groups receive different government benefits.

Once in a while, however, events provide the equivalent of a controlled experiment—

So what were the results? It turned out that Medicaid made a big difference. Those on Medicaid received

60% more mammograms

35% more outpatient care

30% more hospital care

20% more cholesterol checks

Medicaid recipients were also

70% more likely to have a consistent source of care

55% more likely to see the same doctor over time

45% more likely to have had a Pap test within the last year (for women)

40% less likely to need to borrow money or skip payment on other bills because of medical expenses

25% percent more likely to report themselves in “good” or “excellent” health

15% more likely to use prescription drugs

15% more likely to have had a blood test for high blood sugar or diabetes

10% percent less likely to screen positive for depression

In short, Medicaid led to major improvements in access to medical care and the well-

Quick Review

Health insurance satisfies an important need because expensive medical treatment is unaffordable for most families. Private health insurance has an inherent problem: the adverse selection death spiral. Screening by insurance companies reduces the problem, and employment-

based health insurance, the way most Americans are covered, avoids it altogether. The majority of Americans not covered by private insurance are covered by Medicare, which is a non-

means- tested single- payer system for those over 65, and Medicaid, which is means-tested. Compared to other wealthy countries, the United States depends more heavily on private health insurance, has higher health care spending per person, higher administrative costs, and higher drug prices, but without clear evidence of better health outcomes.

Health care costs everywhere are increasing rapidly due to medical progress. The 2010 ACA legislation was designed to address the large and growing share of American uninsured and to reduce the rate of growth of health care spending.

18-3

Question 18.7

If you are enrolled in a four-

year degree program, it is likely that you are required to enroll in a health insurance program run by your school unless you can show proof of existing insurance coverage.. Explain how you and your parents benefit from this health insurance program even though, given your age, it is unlikely that you will need expensive medical treatment.

Explain how your school’s health insurance program avoids the adverse selection death spiral.

Question 18.8

According to its critics, what accounts for the higher costs of the U.S. health care system compared to those of other wealthy countries?

Solutions appear at back of book.