Wages and Labor Supply

Suppose that Clive’s wage rate doubles, from $10 to $20 per hour. How will he change his time allocation?

You could argue that Clive will work longer hours, because his incentive to work has increased: by giving up an hour of leisure, he can now gain twice as much money as before. But you could equally well argue that he will work less, because he doesn’t need to work as many hours to generate the income to pay for the goods he wants.

As these opposing arguments suggest, the quantity of labor Clive supplies can either rise or fall when his wage rate rises. To understand why, let’s recall the distinction between substitution effects and income effects that we learned in Chapter 10 and its appendix. We saw there that a price change affects consumer choice in two ways: by changing the opportunity cost of a good in terms of other goods (the substitution effect) and by making the consumer richer or poorer (the income effect).

Now think about how a rise in Clive’s wage rate affects his demand for leisure. The opportunity cost of leisure—

So in the case of labor supply, the substitution effect and the income effect work in opposite directions. If the substitution effect is so powerful that it dominates the income effect, an increase in Clive’s wage rate leads him to supply more hours of labor. If the income effect is so powerful that it dominates the substitution effect, an increase in the wage rate leads him to supply fewer hours of labor.

The individual labor supply curve shows how the quantity of labor supplied by an individual depends on that individual’s wage rate.

We see, then, that the individual labor supply curve—the relationship between the wage rate and the number of hours of labor supplied by an individual worker—

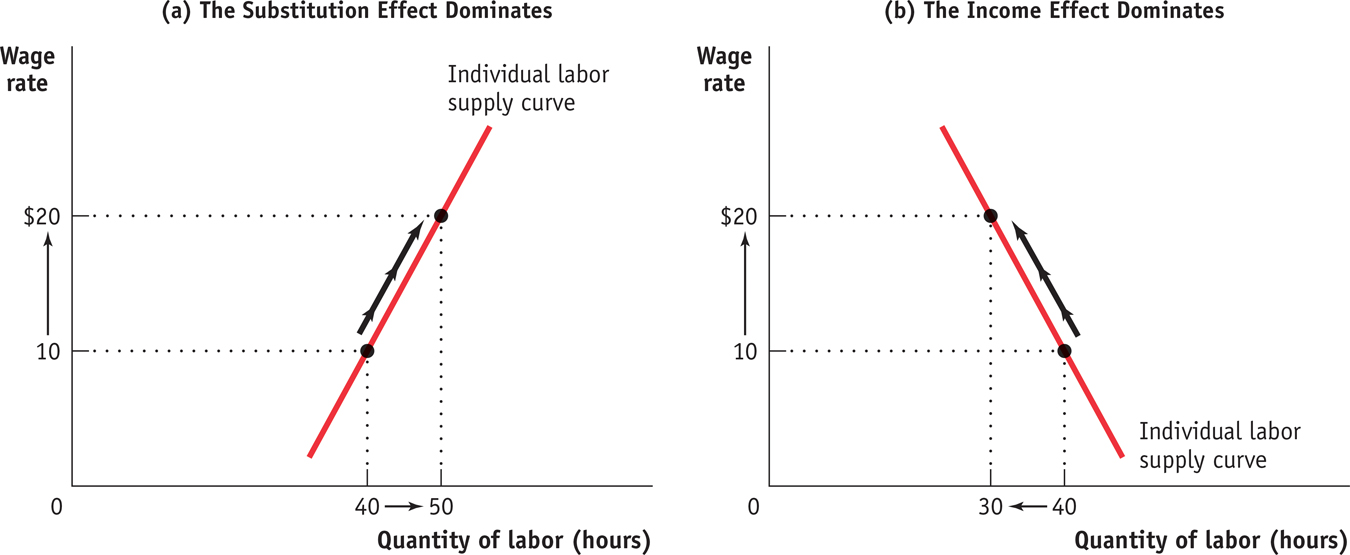

Figure 19-11 illustrates the two possibilities for labor supply. If the substitution effect dominates the income effect, the individual labor supply curve slopes upward; panel (a) shows an increase in the wage rate from $10 to $20 per hour leading to a rise in the number of hours worked from 40 to 50. However, if the income effect dominates, the quantity of labor supplied goes down when the wage rate increases. Panel (b) shows the same rise in the wage rate leading to a fall in the number of hours worked from 40 to 30. (Economists refer to an individual labor supply curve that contains both upward-

19-11

The Individual Labor Supply Curve

Is a negative response of the quantity of labor supplied to the wage rate a real possibility? Yes: many labor economists believe that income effects on the supply of labor may be somewhat stronger than substitution effects. The most compelling piece of evidence for this belief comes from Americans’ increasing consumption of leisure over the past century. At the end of the nineteenth century, wages adjusted for inflation were only about one-

Why You Can’t Find a Cab When It’s Raining

Everyone says that you can’t find a taxi in New York when you really need one—

When it’s raining, drivers get more fares and therefore earn more per hour. But it seems that the income effect of this higher wage rate outweighs the substitution effect.

This behavior led the authors of the study to question drivers’ rationality. They point out that if taxi drivers thought in terms of the long run, they would realize that rainy days and nice days tend to average out and that their high earnings on a rainy day don’t really affect their long-

Indeed, experienced drivers (who have probably figured this out) are less likely than inexperienced drivers to go home early on a rainy day. But leaving such issues to one side, the study does seem to show clear evidence of a labor supply curve that slopes downward instead of upward, thanks to income effects.

These findings give us a deeper understanding of the economics behind the spectacular rise of Uber, the company that matches passengers with available drivers for hire via a smartphone app. The fact that taxi drivers tend to head home just when people really need a ride has provided an opportunity for Uber: by allowing its drivers to charge more when demand shifts outward (a practice called surge pricing), Uber puts more drivers on the road despite the income effects on taxi drivers’ labor supply curves.