Comparative Advantage and International Trade, in Reality

Look at the label on a manufactured good sold in the United States, and there’s a good chance you will find that it was produced in some other country—

Should all this international exchange of goods and services be celebrated, or is it cause for concern? Politicians and the public often question the desirability of international trade, arguing that the nation should produce goods for itself rather than buying them from foreigners. Industries around the world demand protection from foreign competition: Japanese farmers want to keep out American rice, American steelworkers want to keep out European steel. And these demands are often supported by public opinion.

Economists, however, have a very positive view of international trade. Why? Because they view it in terms of comparative advantage. As we learned from our example of U.S. large jets and Brazilian small jets, international trade benefits both countries. Each country can consume more than if it didn’t trade and remained self-

PITFALLS: MISUNDERSTANDING COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

MISUNDERSTANDING COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Students do it, pundits do it, and politicians do it all the time: they confuse comparative advantage with absolute advantage. For example, back in the 1980s, when the U.S. economy seemed to be lagging behind that of Japan, one often heard commentators warn that if we didn’t improve our productivity, we would soon have no comparative advantage in anything.

What those commentators meant was that we would have no absolute advantage in anything—

But just as Brazil, in our example, was able to benefit from trade with the United States (and vice versa) despite the fact that the United States was better at manufacturing both large and small jets, in real life nations can still gain from trade even if they are less productive in all industries than the countries they trade with.

| Pajama Republics |

In April 2013, a terrible industrial disaster made world headlines: in Bangladesh, a building housing five clothing factories collapsed, killing more than a thousand garment workers trapped inside. Attention soon focused on the substandard working conditions in those factories, as well as the many violations of building codes and safety procedures-

While the story provoked a justified outcry, it also highlighted the remarkable rise of Bangladesh’s clothing industry, which has become a major player in world markets—

It’s not that Bangladesh has especially high productivity in clothing manufacturing. In fact, recent estimates by the consulting firm McKinsey and Company suggest that it’s about a quarter less productive than China. Rather, it has even lower productivity in other industries, giving it a comparative advantage in clothing manufacturing. This is typical in poor countries, which often rely heavily on clothing exports during the early phases of their economic development. An official from one such country once joked, “We are not a banana republic—

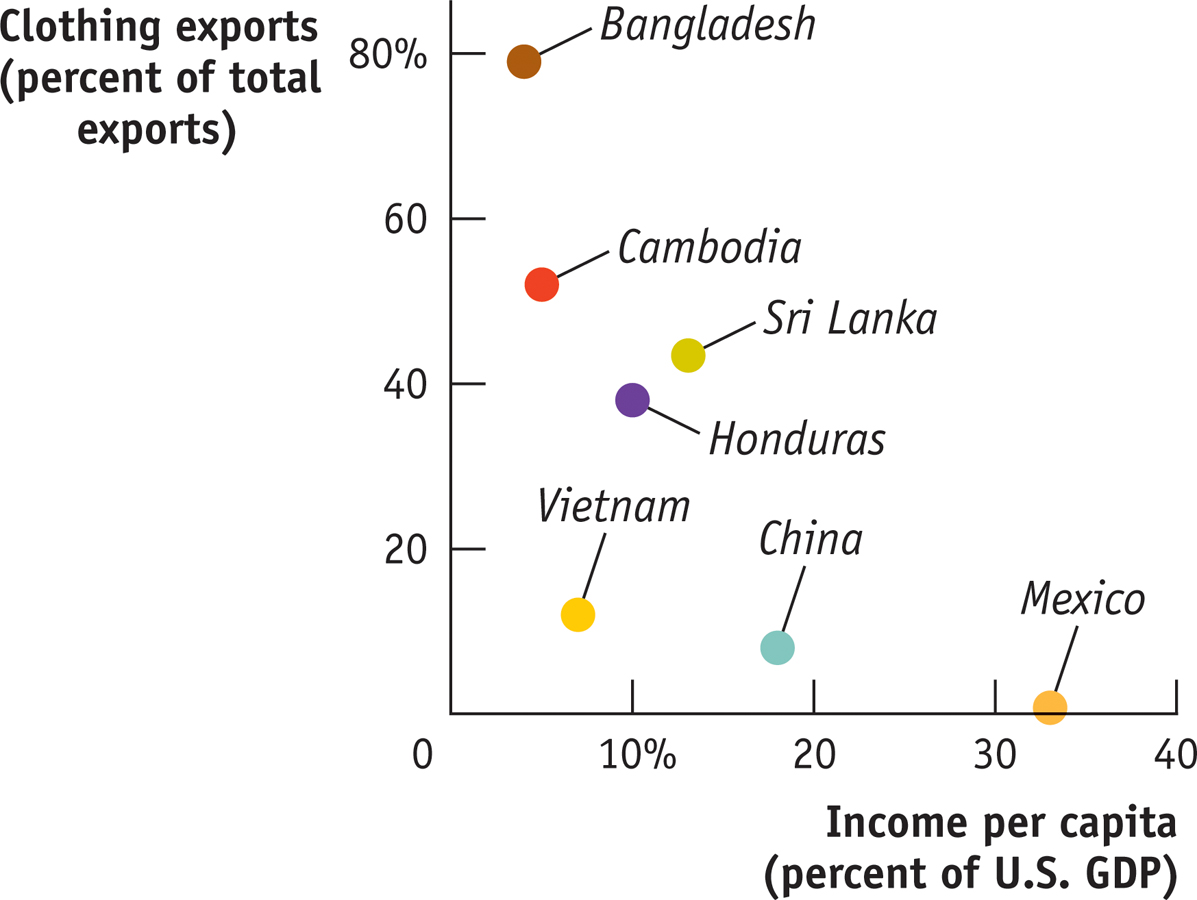

The figure plots the per capita income of several such “pajama republics” (the total income of the country divided by the size of the population) against the share of total exports accounted for by clothing; per capita income is measured as a percentage of the U.S. level in order to give you a sense of just how poor these countries are. As you can see, they are very poor indeed—

It’s worth pointing out, by the way, that relying on clothing exports is by no means necessarily a bad thing, despite tragedies like the Bangladesh factory disaster. Indeed, Bangladesh, although still desperately poor, is more than twice as rich as it was two decades ago, when it began its dramatic rise as a clothing exporter. (Also see the upcoming Economics in Action on Bangladesh.)

Source: WTO.