Different Taxes, Different Principles

Why are some taxes progressive but others regressive? Can’t the government make up its mind?

There are two main reasons for the mixture of regressive and progressive taxes in the U.S. system: the difference between levels of government and the fact that different taxes are based on different principles.

State and especially local governments generally do not make much effort to apply the ability-

Although the federal government is in a better position than state or local governments to apply principles of fairness, it applies different principles to different taxes. We saw an example of this in the preceding Economics in Action. The most important tax, the federal income tax, is strongly progressive, reflecting the ability-

Taxing Income versus Taxing Consumption

The U.S. government taxes people mainly on the money they make, not on the money they spend on consumption. Yet most tax experts argue that this policy badly distorts incentives. Someone who earns income and then invests that income for the future gets taxed twice: once on the original sum and again on any earnings made from the investment.

So a system that taxes income rather than consumption discourages people from saving and investing, instead providing an incentive to spend their income today. And encouraging savings and investing is an important policy goal for two reasons. First, empirical evidence shows that Americans tend to save too little for retirement and health care expenses in their later years. Second, savings and investment both contribute to economic growth.

Moving from a system that taxes income to one that taxes consumption would solve this problem. In fact, the governments of many countries get much of their revenue from a value-

The United States does not have a value-

ECONOMICS in Action: The Top Marginal Income Tax Rate

The Top Marginal Income Tax Rate

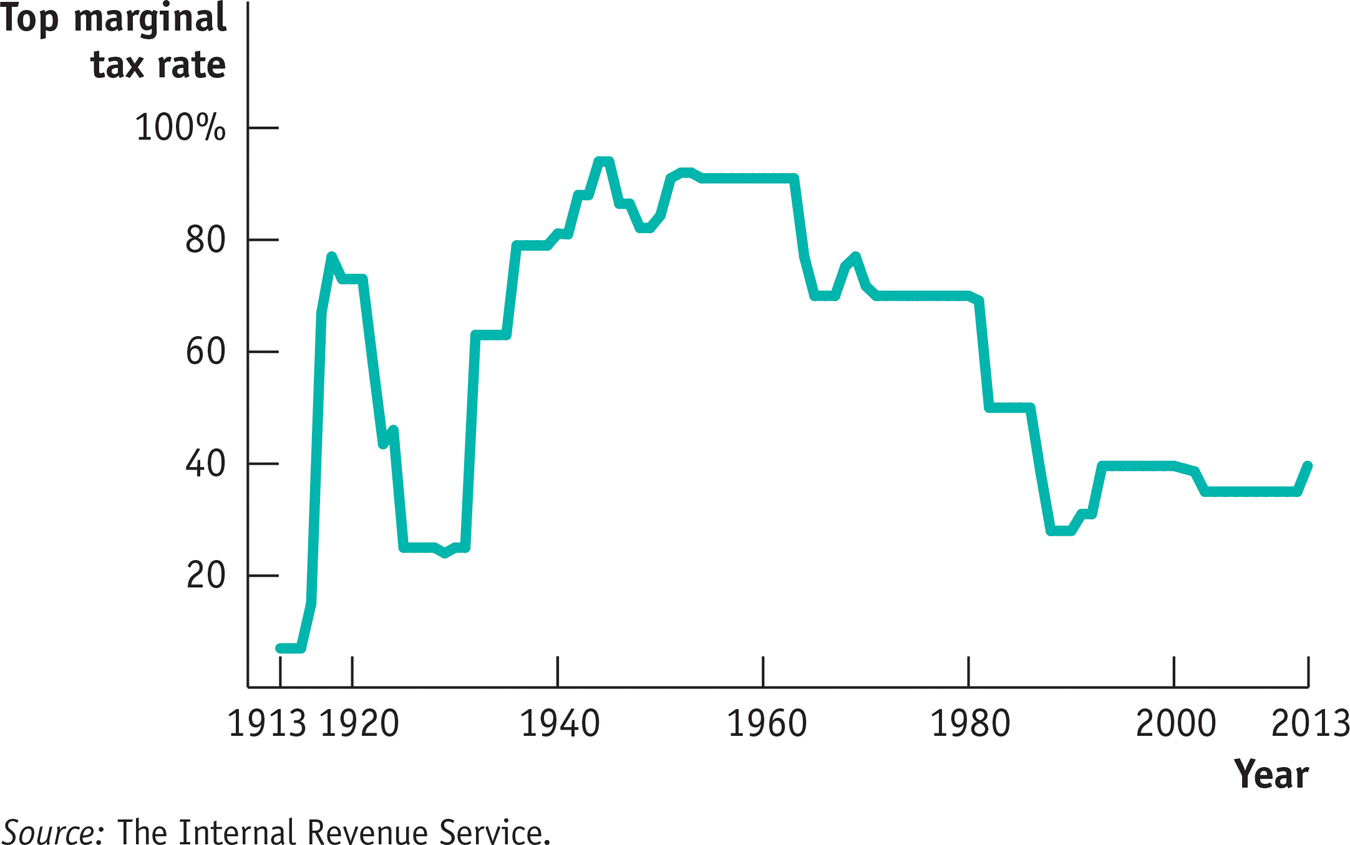

The amount of money an American owes in federal income taxes is found by applying marginal tax rates on successively higher “brackets” of income. For example, in 2013 a single person paid 10% on the first $8,925 of taxable income (that is, income after subtracting exemptions and deductions); 15% on the next $27,325; and so on up to a top rate of 39.6% on his or her income, if any, over $400,000. Relatively few people (less than 1% of taxpayers) have incomes high enough to pay the top marginal rate. In fact, more than 75% of Americans pay no income tax or they fall into either the 10% or 15% bracket. But the top marginal income tax rate is often viewed as a useful indicator of the progressiv-

Figure 7-11 shows the top marginal income tax rate from 1913, when the U.S. government first imposed an income tax, to 2013. The first big increase in the top marginal rate came during World War I (1914) and was reversed after the war ended (1918). After that, the figure is dominated by two big changes: a huge increase in the top marginal rate during the administration of Franklin Roosevelt (1933–

7-11

The Top Marginal Tax

Quick Review

Every tax consists of a tax base and a tax structure.

Among the types of taxes are income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, profits taxes, property taxes, and wealth taxes.

Tax systems are classified as being proportional, progressive, or regressive.

Progressive taxes are often justified by the ability-

to- pay principle. But strongly progressive taxes lead to high marginal tax rates, which create major incentive problems. The United States has a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes. However, the overall structure of taxes is progressive.

7-4

Question 7.9

An income tax taxes 1% of the first $10,000 of income and 2% on all income above $10,000.

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $5,000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $20,000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

Is this income tax proportional, progressive, or regressive?

Question 7.10

When comparing households at different income levels, economists find that consumption spending grows more slowly than income. Assume that when income grows by 50%, from $10,000 to $15,000, consumption grows by 25%, from $8,000 to $10,000. Compare the percent of income paid in taxes by a family with $15,000 in income to that paid by a family with $10,000 in income under a 1% tax on consumption purchases. Is this a proportional, progressive, or regressive tax?

Question 7.11

True or false? Explain your answers.

Payroll taxes do not affect a person’s incentive to take a job because they are paid by employers.

A lump-

sum tax is a proportional tax because it is the same amount for each person.

Solutions appear at back of book.

Amazon versus BarnesandNoble.com

In 2014, comparison shoppers in about half of the United States found that the final price of a book on Amazon was cheaper than on its competitor, BarnesandNoble.com. Why? It’s simply a matter of taxes—

According to the law, online retailers without a physical presence in a given state can sell products without collecting sales tax. (Customers are supposed to report the transaction and pay the sales tax, which they—

In contrast, the bricks-

7-6

Comparison Shopping for A Deadly indifference by Marshall Jevons

|

Amazon |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Price of book |

$20.69 |

$20.69 |

|

California sales tax (7.5%) |

0 |

$1.45 |

|

Shipping fee |

$3.99 |

$3.99 |

|

Final price |

$20.69 |

$22.14 |

TABLE 7-

As reported in the Wall Street Journal, interviews and company documents show that Amazon believes that its avoidance of sales tax collection has been crucial to its success in becoming the dominant retailer of books in the United States. Estimates are that Amazon would have lost as much as $653 million in sales in 2011, or 1.4% of its annual revenue, if it had been forced to collect sales tax.

Since 2012, however, after vigorous pressure from state authorities, Amazon’s ability to avoid collecting sales tax has been greatly curtailed. As of 2014 the number of states it collects sales taxes in has risen from 5 to 19. It’s part of a new strategy by Amazon, to build warehouses in the states in which it collects sales taxes, reasoning that faster delivery will keep customers loyal despite having to pay sales tax. Yet, it’s not hard to understand the view from BarnesandNoble.com that being forced to collect sales tax when Amazon is not deeply hurt its business.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 7.12

What effect do you think the difference in state sales tax collection has on Amazon’s sales versus BarnesandNoble.com’s sales?

What effect do you think the difference in state sales tax collection has on Amazon’s sales versus BarnesandNoble.com’s sales?Question 7.13

Suppose sales tax is collected on all online book sales. From the evidence in this case, what do you think is the incidence of the tax between seller and buyer? What does this imply about the elasticity of supply of books by book retailers? (Hint: Compare the pre-

tax prices of the book.) Suppose sales tax is collected on all online book sales. From the evidence in this case, what do you think is the incidence of the tax between seller and buyer? What does this imply about the elasticity of supply of books by book retailers? (Hint: Compare the pre-tax prices of the book.) Question 7.14

How did Amazon’s tax strategy distort its business behavior? What measures would eliminate these distortions?

How did Amazon’s tax strategy distort its business behavior? What measures would eliminate these distortions?