The Effect of an Excise Tax on Quantities and Prices

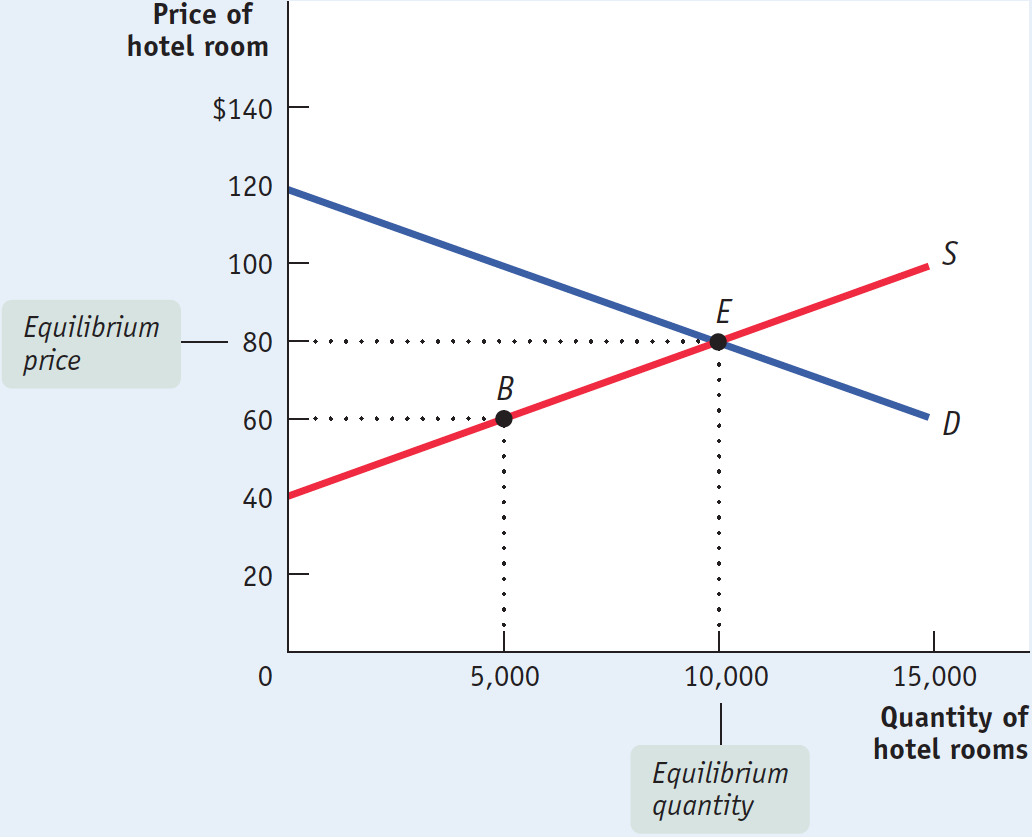

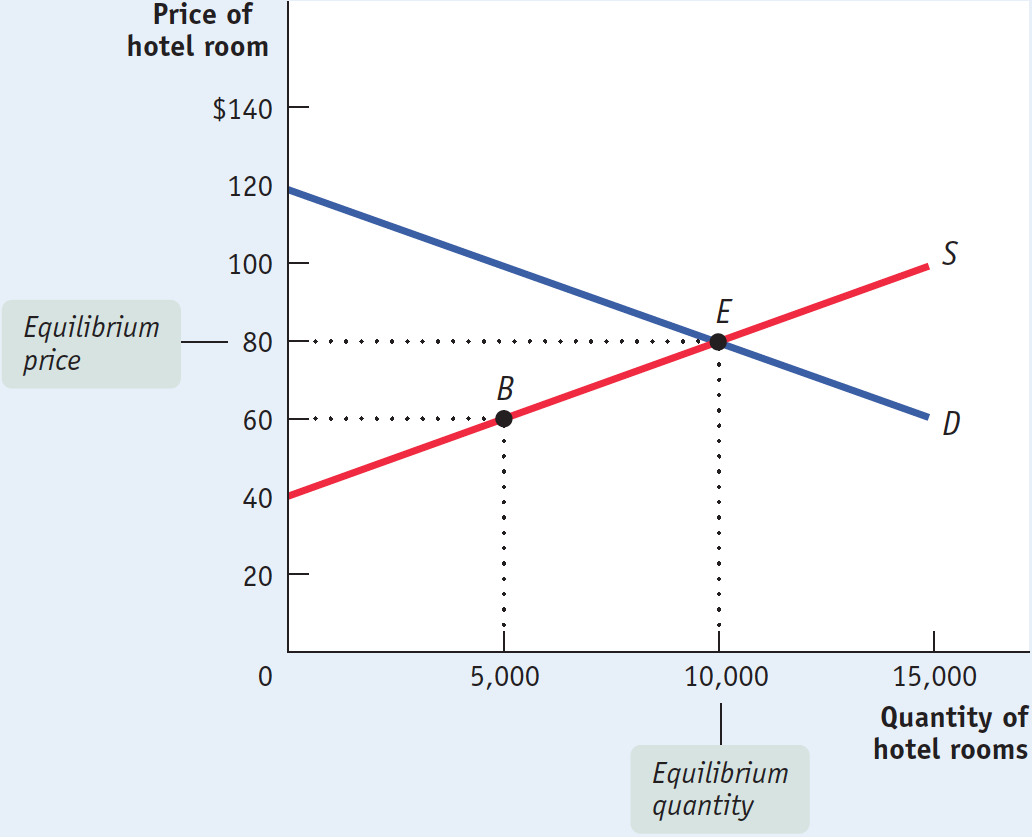

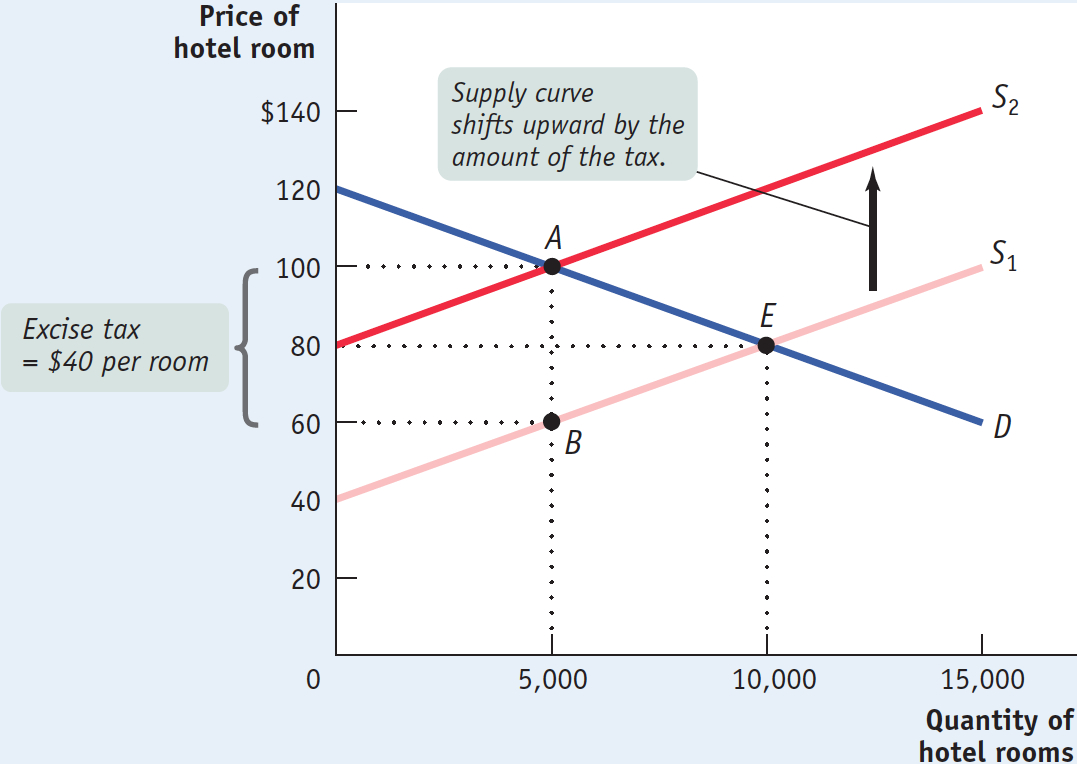

Suppose that the supply and demand for hotel rooms in the city of Potterville are as shown in Figure 7-1. We’ll make the simplifying assumption that all hotel rooms are the same. In the absence of taxes, the equilibrium price of a room is $80 per night and the equilibrium quantity of hotel rooms rented is 10,000 per night.

7-1

The Supply and Demand for Hotel Rooms in Potterville

The Supply and Demand for Hotel Rooms in Potterville In the absence of taxes, the equilibrium price of hotel rooms is $80 a night, and the equilibrium number of rooms rented is 10,000 per night, as shown by point E. The supply curve, S, shows the quantity supplied at any given price, pre-tax. At a price of $60 a night, hotel owners are willing to supply 5,000 rooms, point B. But post-tax, hotel owners are willing to supply the same quantity only at a price of $100: $60 for themselves plus $40 paid to the city as tax.

Now suppose that Potterville’s government imposes an excise tax of $40 per night on hotel rooms—that is, every time a room is rented for the night, the owner of the hotel must pay the city $40. For example, if a customer pays $80, $40 is collected as a tax, leaving the hotel owner with only $40. As a result, hotel owners are less willing to supply rooms at any given price.

What does this imply about the supply curve for hotel rooms in Potterville? To answer this question, we must compare the incentives of hotel owners pre-tax (before the tax is levied) to their incentives post-tax (after the tax is levied).

From Figure 7-1 we know that pre-tax, hotel owners are willing to supply 5,000 rooms per night at a price of $60 per room. But after the $40 tax per room is levied, they are willing to supply the same amount, 5,000 rooms, only if they receive $100 per room—$60 for themselves plus $40 paid to the city as tax. In other words, in order for hotel owners to be willing to supply the same quantity post-tax as they would have pre-tax, they must receive an additional $40 per room, the amount of the tax.

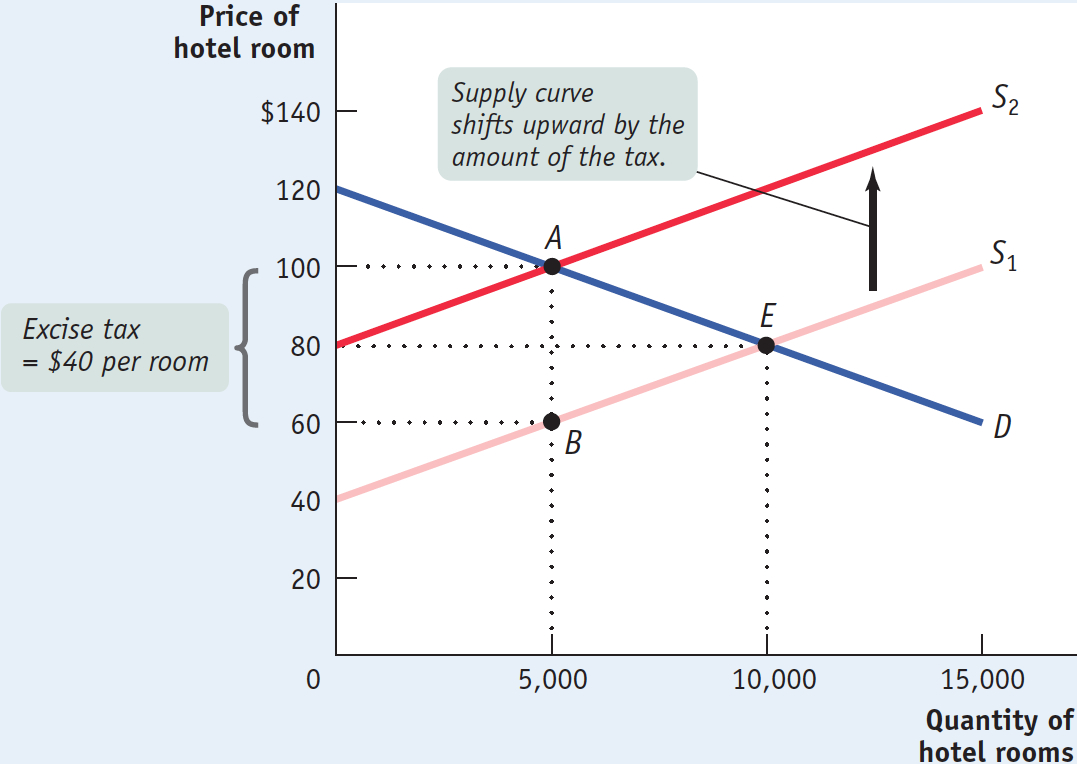

This implies that the post-tax supply curve shifts up by the amount of the tax compared to the pre-tax supply curve. At every quantity supplied, the supply price—the price that producers must receive to produce a given quantity—has increased by $40.

The upward shift of the supply curve caused by the tax is shown in Figure 7-2, where S1 is the pre-tax supply curve and S2 is the post-tax supply curve. As you can see, as a result of the tax the market equilibrium moves from E, at the equilibrium price of $80 per room and 10,000 rooms rented each night, to A, at a market price of $100 per room and only 5,000 rooms rented each night. A is, of course, on both the demand curve D and the new supply curve S2.

7-2

An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Owners

An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Owners A $40 per room tax imposed on hotel owners shifts the supply curve from S1 to S2, an upward shift of $40. The equilibrium price of hotel rooms rises from $80 to $100 a night, and the equilibrium quantity of rooms rented falls from 10,000 to 5,000. Although hotel owners pay the tax, they actually bear only half the burden: the price they receive net of tax falls only $20, from $80 to $60. Guests who rent rooms bear the other half of the burden, because the price they pay rises by $20, from $80 to $100.

Although, $100 is the demand price of 5,000 rooms, hotel owners receive only $60 of that price because they must pay $40 of it in tax. From the point of view of hotel owners, it is as if they were on their original supply curve at point B.

Let’s check this again. How do we know that 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $100? Because the price net of tax is $60, and according to the original supply curve, 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $60, as shown by point B in Figure 7-2.

Does this look familiar? It should. In Chapter 5 we described the effects of a quota on sales: a quota drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. An excise tax does the same thing. As a result of this wedge, consumers pay more and producers receive less.

In our example, consumers—people who rent hotel rooms—end up paying $100 a night, $20 more than the pre-tax price of $80. At the same time, producers—the hotel owners—receive a price net of tax of $60 per room, $20 less than the pre-tax price. In addition, the tax creates missed opportunities: 5,000 potential consumers who would have rented hotel rooms—those willing to pay $80 but not $100 per night—are discouraged from doing so. Correspondingly, 5,000 rooms that would have been made available by hotel owners when they receive $80 are not offered when they receive only $60. Like a quota, this tax leads to inefficiency by distorting incentives and creating missed opportunities for mutually beneficial transactions.

It’s important to recognize that as we’ve described it, Potterville’s hotel tax is a tax on the hotel owners, not their guests—it’s a tax on the producers, not the consumers. Yet the price received by producers, net of tax, falls by only $20, half the amount of the tax, and the price paid by consumers rises by $20. In effect, half the tax is being paid by consumers.

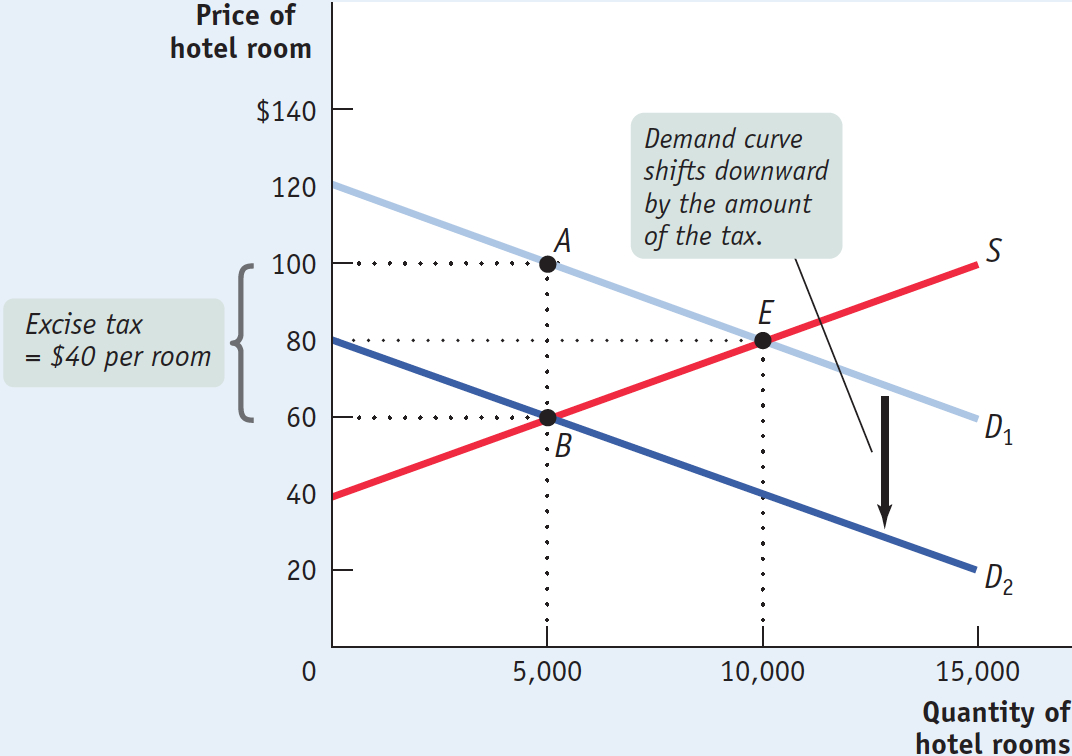

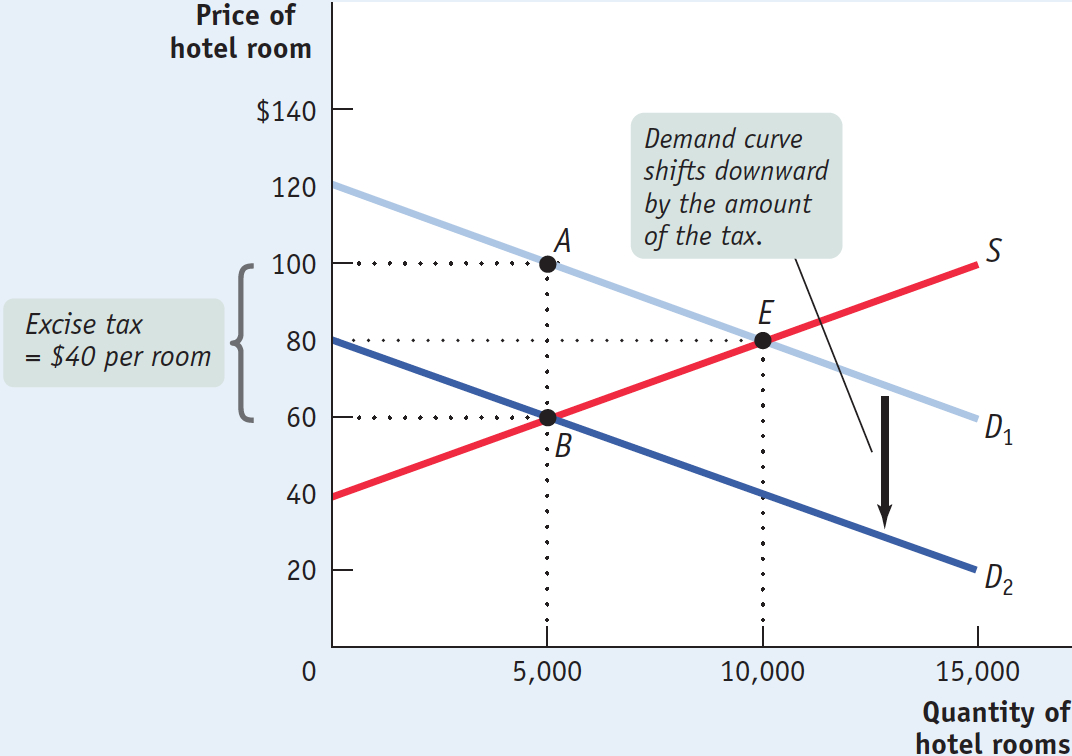

What would happen if the city levied a tax on consumers instead of producers? That is, suppose that instead of requiring hotel owners to pay $40 a night for each room they rent, the city required hotel guests to pay $40 for each night they stayed in a hotel. The answer is shown in Figure 7-3. If a hotel guest must pay a tax of $40 per night, then the price for a room paid by that guest must be reduced by $40 in order for the quantity of hotel rooms demanded post-tax to be the same as that demanded pre-tax. So the demand curve shifts downward, from D1 to D2, by the amount of the tax.

7-3

An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Guests

An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Guests A $40 per room tax imposed on hotel guests shifts the demand curve from D1 to D2, a downward shift of $40. The equilibrium price of hotel rooms falls from $80 to $60 a night, and the quantity of rooms rented falls from 10,000 to 5,000. Although in this case the tax is officially paid by consumers, while in Figure 7-2 the tax was paid by producers, the outcome is the same: after taxes, hotel owners receive $60 per room but guests pay $100. This illustrates a general principle: The incidence of an excise tax doesn’t depend on whether consumers or producers officially pay the tax.

At every quantity demanded, the demand price—the price that consumers must be offered to demand a given quantity—has fallen by $40. This shifts the equilibrium from E to B, where the market price of hotel rooms is $60 and 5,000 hotel rooms are bought and sold. In effect, hotel guests pay $100 when you include the tax. So from the point of view of guests, it is as if they were on their original demand curve at point A.

If you compare Figures 7-2 and 7-3, you will immediately notice that they show equivalent outcomes. In both cases consumers pay $100, producers receive $60, and 5,000 hotel rooms are bought and sold. In fact, it doesn’t matter who officially pays the tax—the outcome is the same.

The incidence of a tax is a measure of who really pays it.

This insight illustrates a general principle of the economics of taxation: the incidence of a tax—who really bears the burden of the tax—is typically not a question you can answer by asking who writes the check to the government. In this particular case, a $40 tax on hotel rooms is reflected in a $20 increase in the price paid by consumers and a $20 decrease in the price received by producers.

Here, regardless of whether the tax is levied on consumers or producers, the incidence of the tax is evenly split between them.