8. Christiansted: Official Map and Guide

8. Christiansted: Official Map and Guide

National Park Service

The following U.S. National Park Service travel brochure for tourists in St. Croix, Virgin Islands, discusses the history of the island’s capital, Christiansted.

Denmark was a latecomer in the race for colonies in the New World. Columbus’ voyages to the Caribbean gave Spain a monopoly in the region for well over a century. But after the English planted a colony in the Lesser Antilles in 1624, the French, the Dutch, and eventually Danes joined the scramble for empire. Seeking islands on which to cultivate sugar as well as an outlet for trade, the Danish West India & Guinea Company (a group of nobles and merchants chartered by the Crown) took possession of St. Thomas in 1672 and its neighbor St. John in 1717. Because neither island was well suited to agriculture, the company in 1733 purchased St. Croix—a larger, flatter, and more fertile island, 40 miles south—from France. Colonization of St. Croix began the next year, after troops put down a slave revolt on St. John.

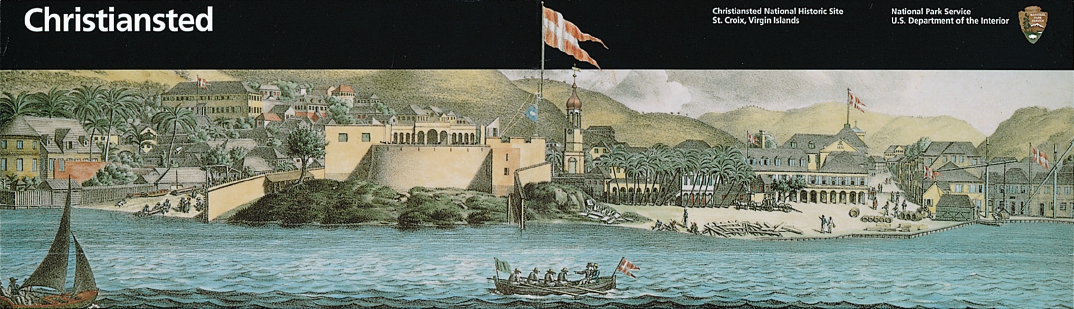

For their first settlement, the Danes chose a good harbor on the northeast coast, the site of an earlier French village named Bassin. Their leader Frederick Moth was a man of some vision. Among his accomplishments were a plan for a new town, which he named Christiansted in honor of the reigning monarch, King Christian VI, and a survey of the island into plantations of 150 acres, which were offered at bargain prices to new settlers. The best land came under cultivation and dozens of sugar factories began operating. Population approached 10,000, of which nearly 9,000 were slaves imported from West Africa to work in the fields.

Even with this growth St. Croix’s economy did not flourish. The planters chaffed under the restrictive trading practices of the DWI&G Company. This monopoly so burdened planters with regulations that they persuaded the king to take over the islands in 1755. Crown administration coincided with the beginning of a long period of growth for the cane sugar industry. St. Croix became the capital of the “Danish Islands of America,” as they were then called, and royal governors took up residence in Christiansted. For the next century and a half, the town’s fortunes were tied to St. Croix’s sugar industry. Between 1760 and 1820 the economy boomed. Population rose dramatically, in part because free-trade policies and neutrality attracted settlers from other islands—hence the prevalence of English culture on this Danish island with a French name—and exports of sugar and rum soared. Capital was available, sugar prices were high, labor cheap. Planters, merchants, and traders—most of them—reaped great profits, which were reflected in the fine architecture of town and country. This golden age was, within a few decades, eclipsed by the rise of the beet sugar industry in Europe and North America. A drop in the price of cane sugar, an increase in planters’ debts, drought, hurricanes, and the rising cost of labor after slavery was abolished in 1848 all contributed to economic decline. As the 19th century wore on, St. Croix became little more than a marginal sugar producer, her era of fabulous wealth now a thing of the past. When the United States purchased the Danish West Indies in 1917, it was for the islands’ strategic harbors, not their agriculture. The lovely town of Christiansted is a link to the old way of life here, with all its elegance, complexity, and contradiction.