CULMINATING ACTIVITY

● CULMINATING ACTIVITY ●

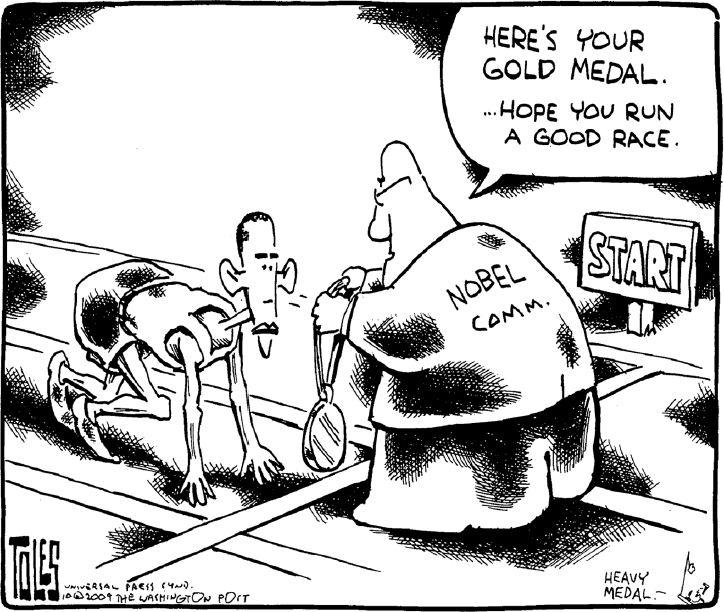

The political cartoon and article that follow make similar claims about the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to President Barack Obama in 2009, but in very different ways. The Tom Toles cartoon appeared in the Washington Post; the article appeared in the London Times. Discuss the way each argument is developed and the likely impact of each on its audience.

Comment: Absurd Decision on Obama Makes a Mockery of the Nobel Peace Prize

Michael Binyon

The award of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize to President Obama will be met with widespread incredulity, consternation in many capitals and probably deep embarrassment by the President himself.

Rarely has an award had such an obvious political and partisan intent. It was clearly seen by the Norwegian Nobel Committee as a way of expressing European gratitude for an end to the Bush Administration, approval for the election of America’s first black president and hope that Washington will honour its promise to re-engage with the world.

Instead, the prize risks looking preposterous in its claims, patronising in its intentions and demeaning in its attempt to build up a man who has barely begun his period in office, let alone achieved any tangible outcome for peace.

The pretext for the prize was Mr. Obama’s decision to “strengthen international diplomacy and co-operation between peoples.” Many people will point out that, while the President has indeed promised to “reset” relations with Russia and offer a fresh start to relations with the Muslim world, there is little so far to show for his fine words.

5

East–West relations are little better than they were six months ago, and any change is probably due largely to the global economic downturn; and America’s vaunted determination to re-engage with the Muslim world has failed to make any concrete progress towards ending the conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians.

There is a further irony in offering a peace prize to a president whose principal preoccupation at the moment is when and how to expand the war in Afghanistan.

The spectacle of Mr. Obama mounting the podium in Oslo to accept a prize that once went to Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi and Mother Theresa would be all the more absurd if it follows a White House decision to send up to 40,000 more U.S. troops to Afghanistan. However just such a war may be deemed in Western eyes, Muslims would not be the only group to complain that peace is hardly compatible with an escalation in hostilities.

The Nobel Committee has made controversial awards before. Some have appeared to reward hope rather than achievement: the 1976 prize for the two peace campaigners in Northern Ireland, Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan, was clearly intended to send a signal to the two battling communities in Ulster. But the political influence of the two winners turned out, sadly, to be negligible.

In the Middle East, the award to Menachem Begin of Israel and Anwar Sadat of Egypt in 1978 also looks, in retrospect, as naive as the later award to Yassir Arafat, Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin—although it could be argued that both the Camp David and Oslo accords, while not bringing peace, were at least attempts to break the deadlock.

10

Mr. Obama’s prize is more likely, however, to be compared with the most contentious prize of all: the 1973 prize to Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho for their negotiations to end the Vietnam War. Dr. Kissinger was branded a warmonger for his support for the bombing campaign in Cambodia; and the Vietnamese negotiator was subsequently seen as a liar whose government never intended to honour a peace deal but was waiting for the moment to attack South Vietnam.

Mr. Obama becomes the third sitting U.S. President to receive the prize. The committee said today that he had “captured the world’s attention.” It is certainly true that his energy and aspirations have dazzled many of his supporters. Sadly, it seems they have so bedazzled the Norwegians that they can no longer separate hopes from achievement. The achievements of all previous winners have been diminished.