Cells receive several types of signals

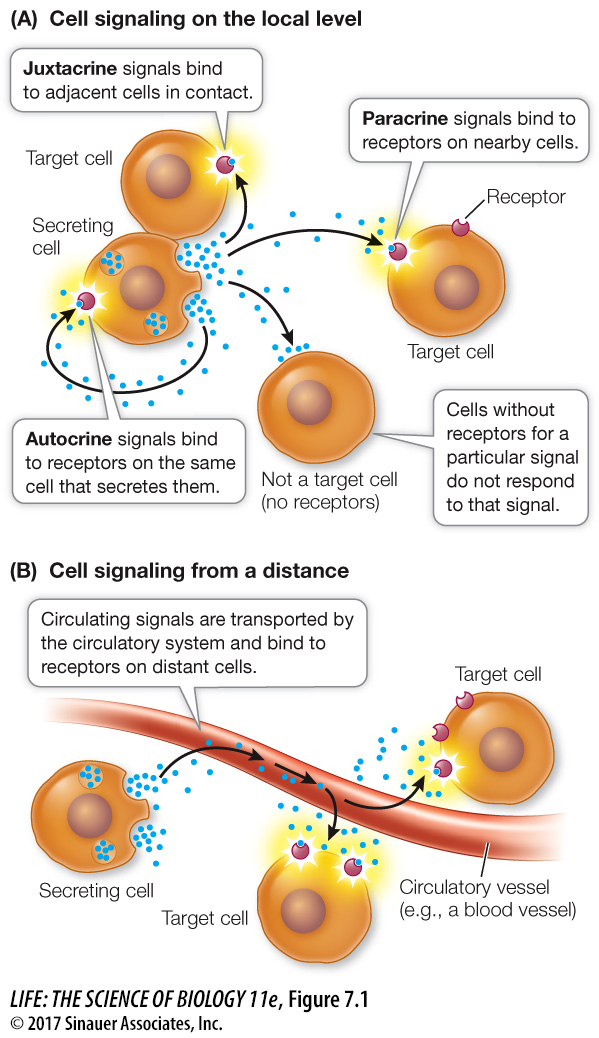

The environment is full of signals. For example, our sense organs allow us to respond to light (a physical signal), or odors and tastes (chemical signals). Bacteria and protists can respond to small chemical changes in their surroundings. Plants respond to light as a signal as well as an energy source, for example, by growing toward the source of light. A cell that is deep inside a large multicellular organism and far away from the exterior environment receives signals from neighboring cells and the surrounding extracellular fluids. In multicellular organisms, chemical signals are often made in one part of the body and arrive at target cells by local diffusion or by circulation in the blood or the plant vascular system. Chemical cell signals are usually present in tiny concentrations (as low as 10–10 M) (see Chapter 2 for an explanation of molar concentrations) and differ in their sources and mode of delivery (Figure 7.1):

Autocrine signals diffuse to and affect the cells that make them. For example, many tumor cells reproduce uncontrollably because they both make, and respond to, signals that stimulate cell division.

Juxtacrine signals affect only cells right next to and in contact with the cell producing the signal. This type of signaling is especially common during development, when cells are in groups and changing to become specialized.

Paracrine signals diffuse to and affect nearby cells. An example occurs in inflammation when the skin is cut. Signals from skin cells are sent to nearby blood cells to aid in healing (see Key Concept 41.2).

Signals that travel through the circulatory systems of animals or the vascular systems of plants are generally called hormones.

Activity 7.1 Chemical Signaling Systems