Genetic screening can be done by examining the phenotype

Genetic screening can involve examining a protein or other chemical that is relevant to a phenotype associated with a particular disease. Perhaps the best example is the test for phenylketonuria (PKU), which has made it possible to identify the disease in newborns, so that treatment can be started immediately. It is very likely that you were screened as a newborn for PKU.

Initially, babies born with PKU have a normal phenotype because excess phenylalanine in their blood before birth diffuses across the placenta to the mother’s circulatory system. Since the mother is almost always heterozygous, and therefore has adequate phenylalanine hydroxylase activity, her body metabolizes the excess phenylalanine from the fetus. After birth, however, the baby begins to consume protein-

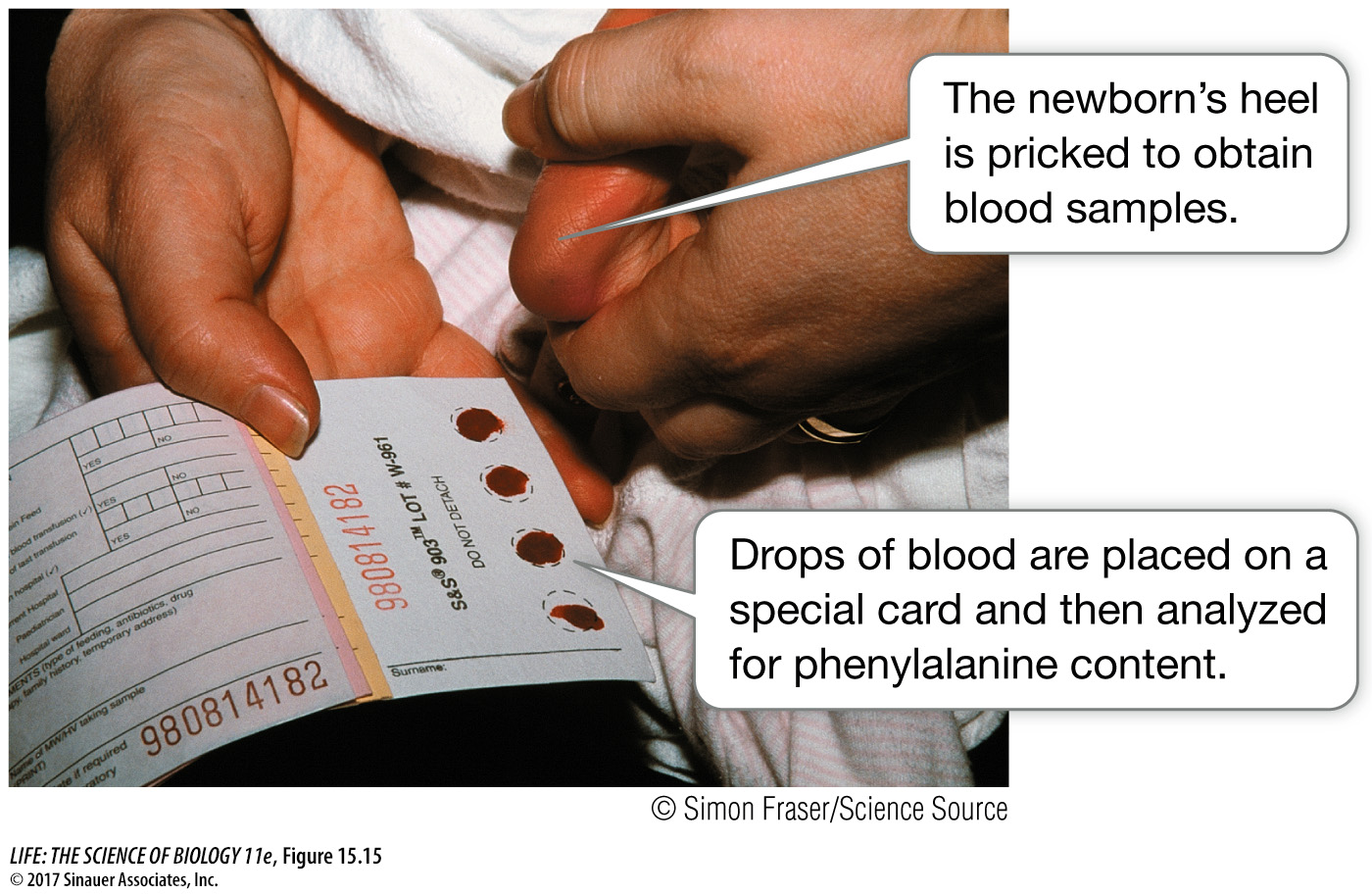

Routine newborn screening for PKU and other diseases began in 1963 with the development of a simple, rapid test for the presence of excess phenylalanine in blood serum (Figure 15.15). This method uses dried blood spots from newborn babies and can be automated so that a screening laboratory can process many samples in a day. Newborn babies’ blood is now screened for up to 35 genetic diseases. Some are common, such as congenital hypothyroidism, which occurs about once in 4,000 births and causes reduced growth and intellectual disability because of low levels of thyroid hormone. With early intervention, many of these infants can be successfully treated. So it is not surprising that newborn screening is legally mandatory in many countries, including the United States and Canada. You were probably screened for several genetic diseases in the first days of your life. Ask your parents which ones!