Conserved developmental genes can lead to parallel evolution

The existence of highly conserved developmental genes makes it likely that similar traits will evolve repeatedly, especially among closely related species. This process is known as parallel evolution, and a good example is provided by a small fish, the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Sticklebacks are widely distributed throughout the Atlantic and Pacific oceans; they are also found in many freshwater lakes and rivers. Marine sticklebacks spend most of their lives at sea but return to fresh water to breed. However, freshwater populations that are isolated in lakes never encounter salt water.

Page 421

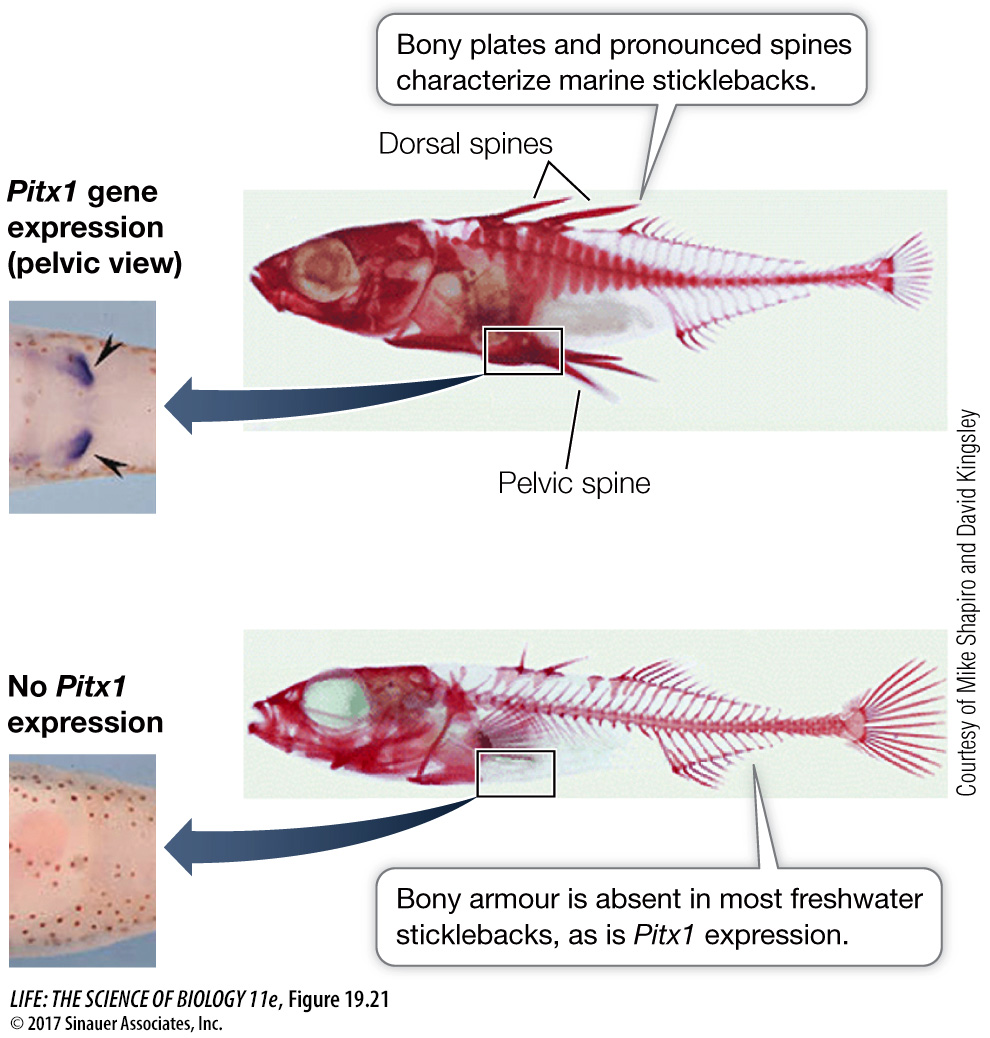

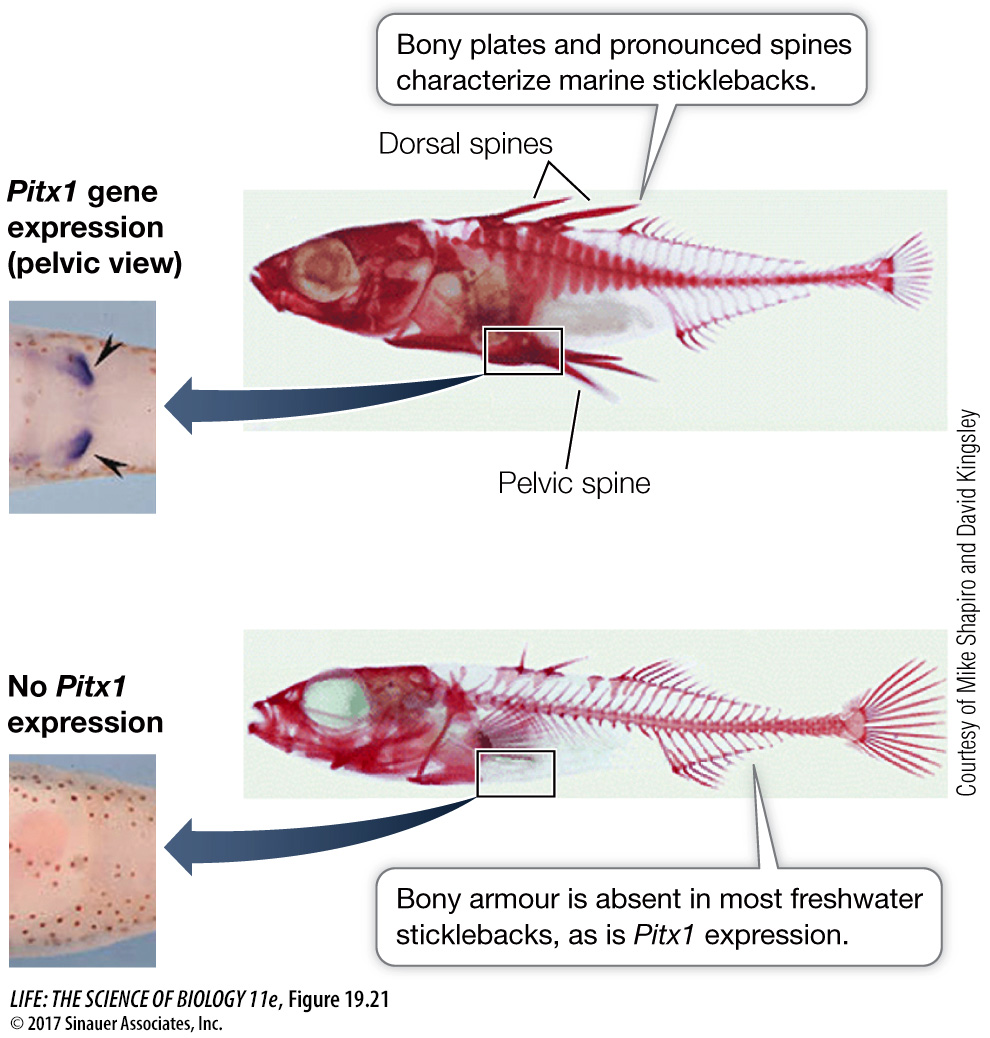

Genetic evidence shows that freshwater populations have arisen from marine populations many times, and independently. Marine sticklebacks have structures that protect them from predatory marine fish; these are bony plates and well-developed pelvic bones with pelvic spines that lacerate the mouths of predators. Freshwater sticklebacks do not face such predatory dangers; their body armor is greatly reduced, and their dorsal and pelvic spines are shorter or even lacking (Figure 19.21).

Figure 19.21 Parallel Phenotypic Evolution in Sticklebacks A developmental gene, Pitx1, encodes a transcription factor that stimulates the production of plates and spines. This gene is active in marine sticklebacks, but mutated and inactive in various freshwater populations of the fish. The fact that this mutation is found in geographically distant and isolated freshwater populations is evidence for parallel evolution.

The differences between marine and freshwater sticklebacks are not induced by environmental conditions. Marine species reared in fresh water still grow armor and spines. The differences are due to the expression of a developmental regulatory gene, Pitx1. Pitx1 codes for a transcription factor normally expressed in regions of the developing embryo that in marine sticklebacks form the head, trunk, tail, and pelvis. However, in separate and long-isolated populations of freshwater sticklebacks from Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Iceland, the Pitx1 gene is no longer expressed in the pelvis, and spines do not develop. This same change in regulatory gene expression has evolved to produce similar phenotypic changes in several independent populations, and is thus a good example of parallel evolution.