As development proceeds, cell fates become restricted

During development, an undifferentiated cell will become part of a particular type of tissue—

Activity 19.2 Cell Fates Simulation

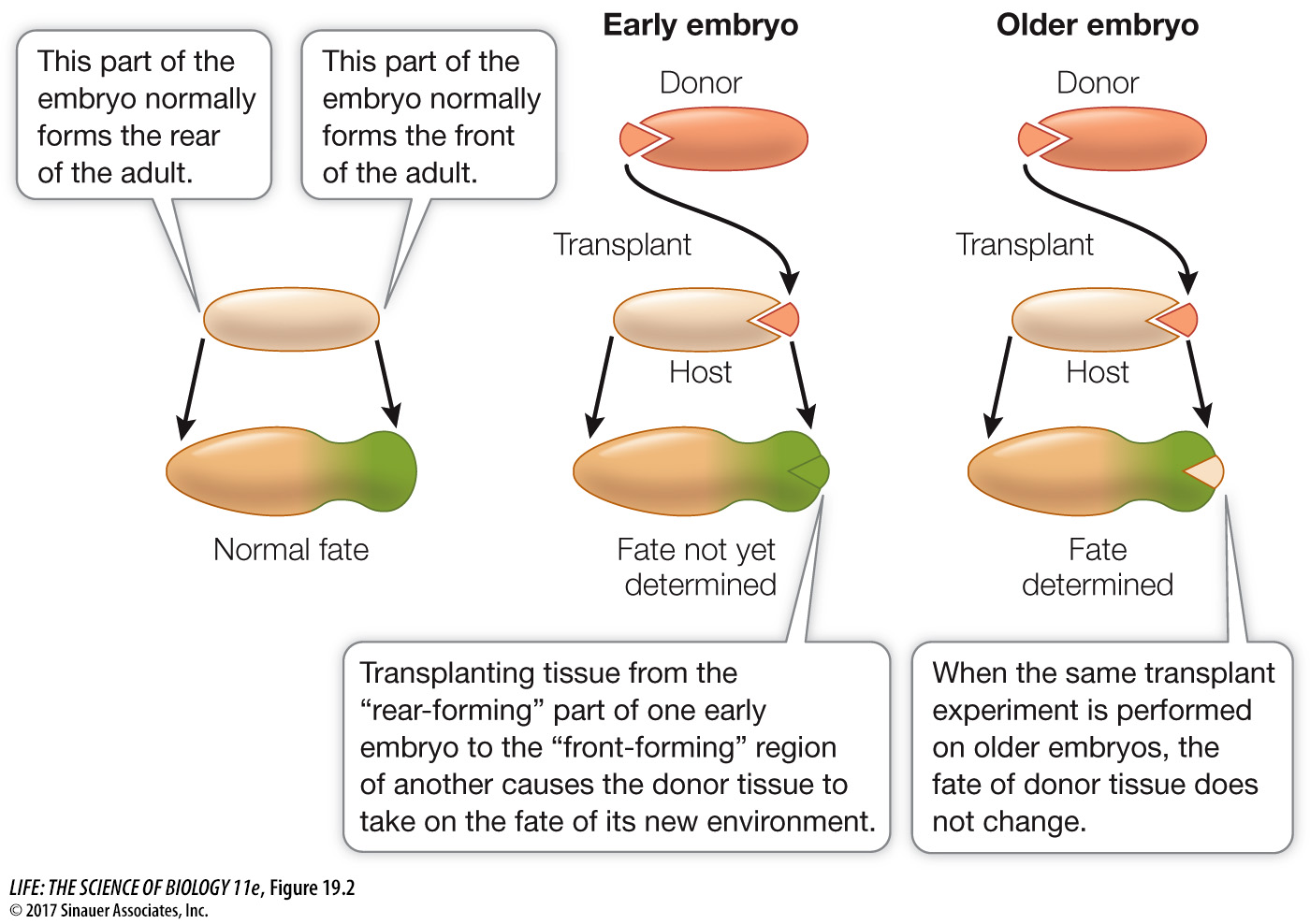

Experiments on amphibian embryos indicate that determination happens early in development. If the donor tissue is from an early-

Cell fate determination is influenced by changes in gene expression as well as the extracellular environment. You can’t see cell fate determination by looking at an embryo under the microscope—

During animal development, cell fate becomes progressively more restricted. This can be thought of in terms of cell potency, which is a cell’s potential to differentiate into other cell types:

The cells of an early embryo are totipotent (toti, “all,” + potent, “capable”); they have the potential to differentiate into any cell type, including more embryonic cells.

In later stages of the embryo, many cells are pluripotent (pluri, “many”); they have the potential to develop into most other cell types, but they cannot form new embryos.

Through later developmental stages, including adulthood, certain stem cells are multipotent; they can differentiate into several different, related cell types. Mesenchymal stem cells (see the opening story of this chapter) are one kind of multipotent stem cell.

Many cells in the mature organism are unipotent; they can produce only one cell type—

their own.