Frequency-dependent selection maintains genetic variation within populations

Natural selection often preserves variation as a polymorphism (the presence of two or more variants of a character in the same population). When the fitness of a given phenotype depends on its frequency in a population, a polymorphism may be maintained by a process known as frequency-dependent selection. Perissodus microlepis, a small fish that lives in Lake Tanganyika in East Africa, provides an example of frequency-dependent selection.

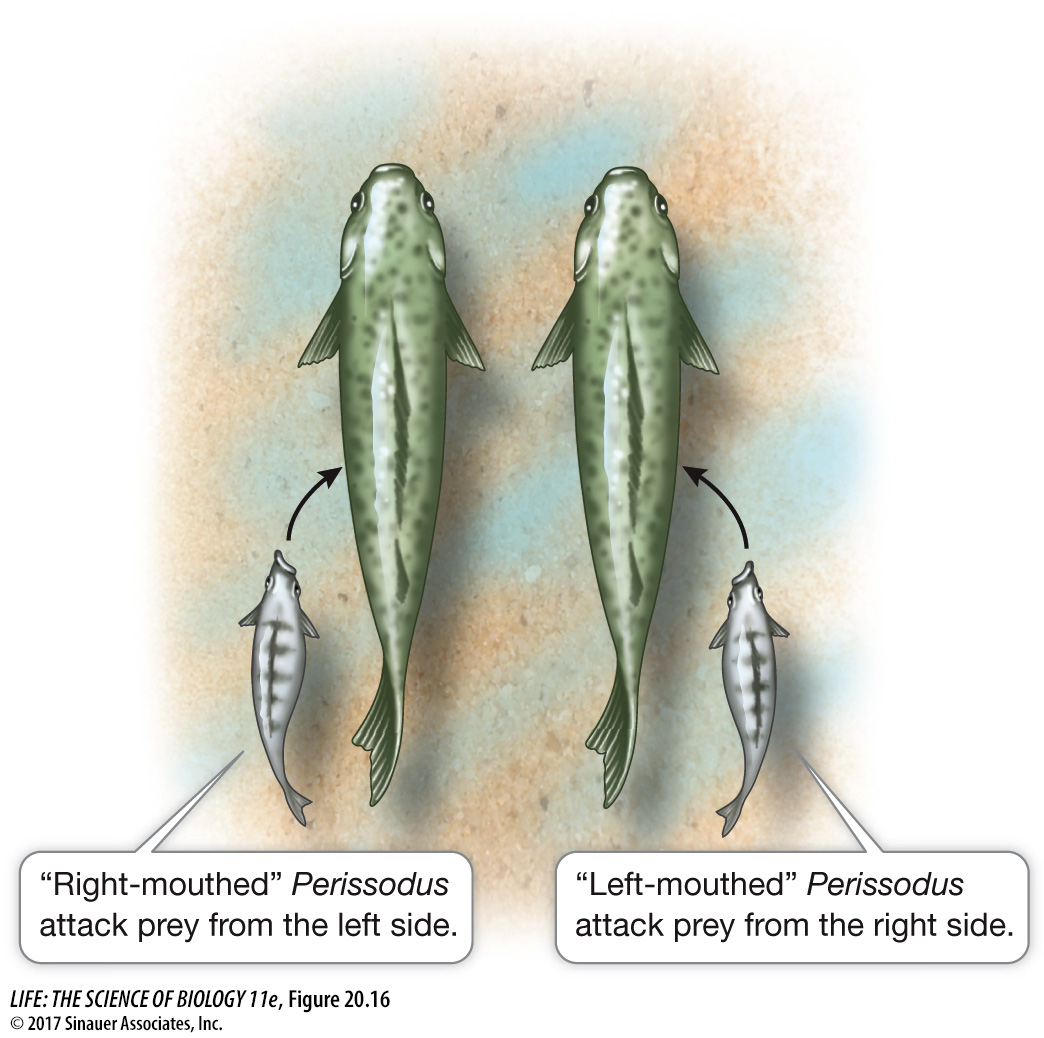

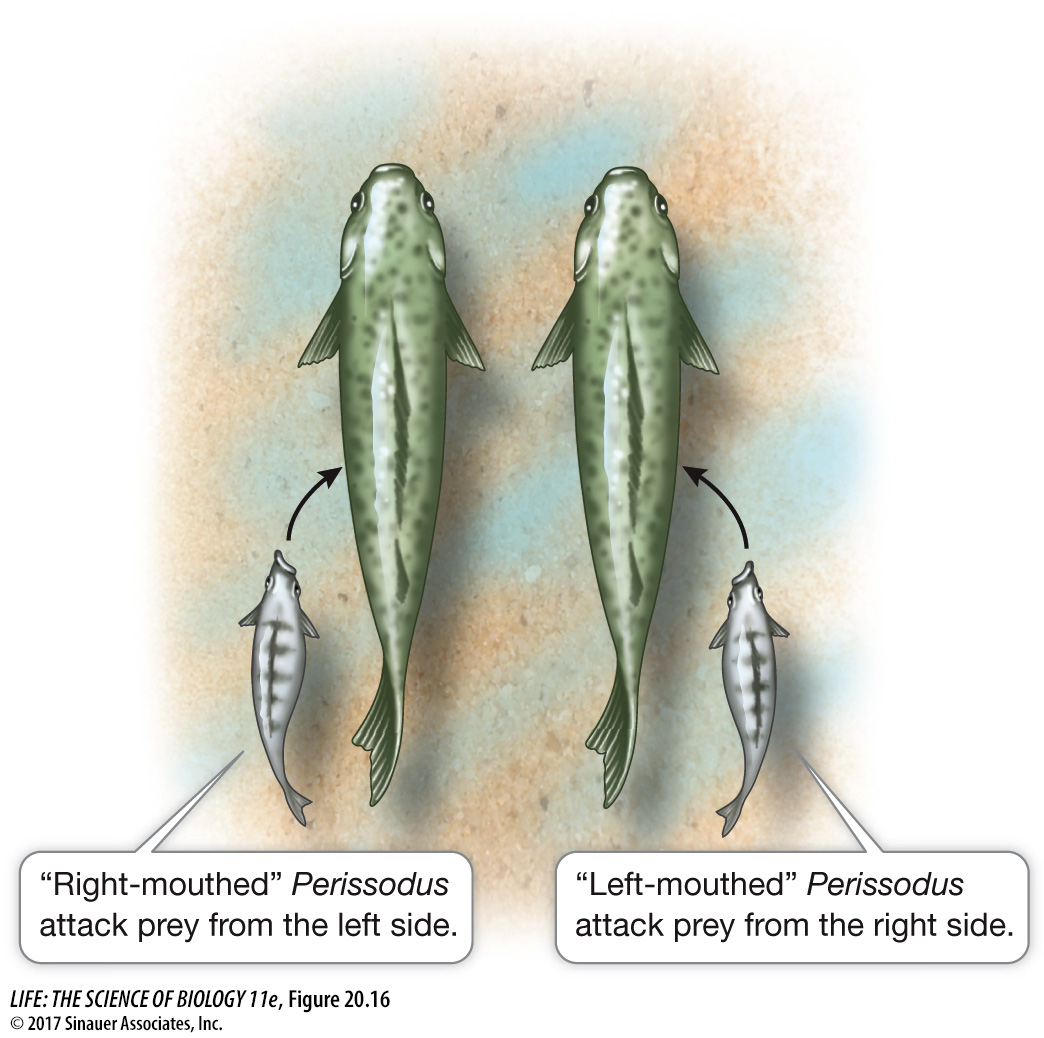

P. microlepis feeds on the scales of other fish, approaching its prey from behind and dashing in to bite off several scales from the prey’s flank. Because of an asymmetrical jaw joint, the mouth of this scale-eating species opens either to the right or to the left; the direction is genetically determined (Figure 20.16). “Right-mouthed” individuals always attack from the victim’s left, and “left-mouthed” individuals always attack from the victim’s right. The distorted mouth enlarges the area of teeth in contact with the prey’s flank, but only if the scale-eater attacks from the appropriate side.

Figure 20.16 A Stable Polymorphism Frequency-dependent selection maintains equal proportions of left- and right-mouthed individuals of the scale-eating fish Perissodus microlepis.

Prey fish are alert to approaching scale-eaters, so attacks are more likely to be successful if the prey must watch both flanks. Vigilance by prey thus favors equal numbers of right- and left-mouthed scale-eaters in a population, because if attacks from one side were more common than the other, prey fish would pay more attention to potential attacks from that side. Over an 11-year study of P. microlepis in Lake Tanganyika, the genetic polymorphism was found to be stable, and the two phenotypes of the scale-eaters remained at about equal frequencies.