Apply What You’ve Learned

Review

20.1

Evolution is directly observable and is a universal principle of life.

20.2

Evolution is the result of five major processes: mutation, natural selection, gene flow, genetic drift, and nonrandom mating.

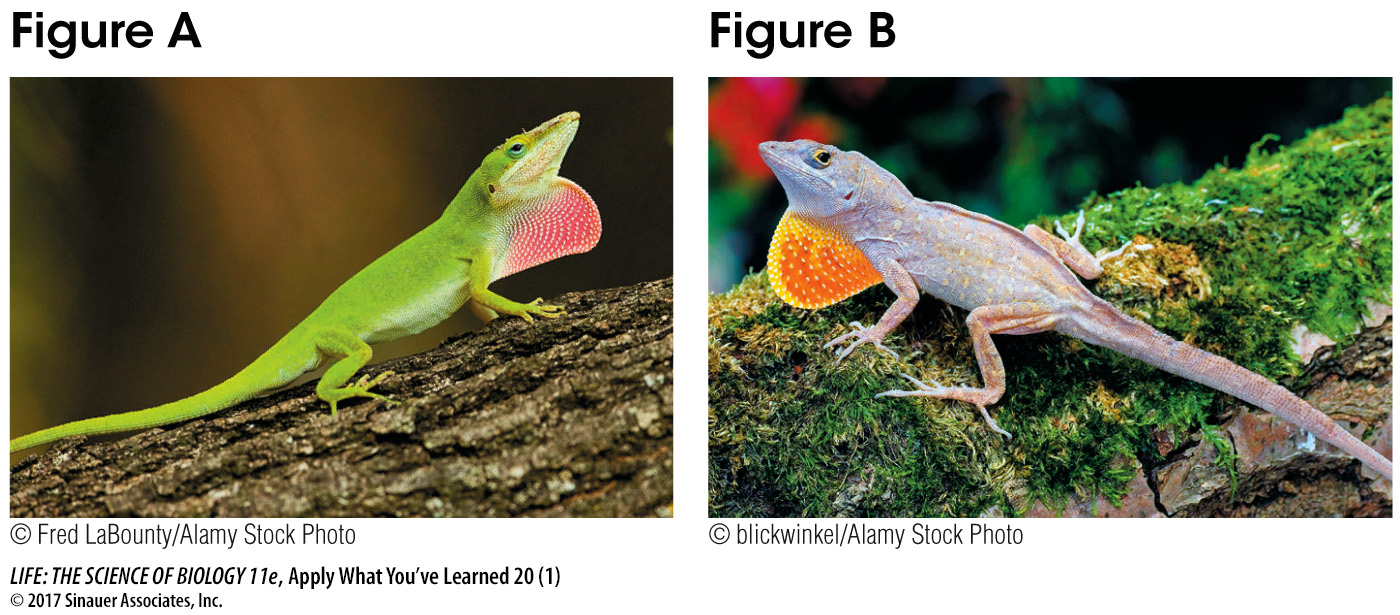

Anoles, an abundant and diverse group of lizards in the American tropics and subtropics, are common subjects of ecological and evolutionary studies. The Carolina (or green) anole, Anolis carolinensis (Figure A), is the only anole native to the southeastern United States. The Cuban brown anole, Anolis sagrei (Figure B), was introduced into south Florida in the late 1800s and has been expanding its range northward since then. When living alone, A. carolinensis occupies habitats from ground level to treetops, whereas A. sagrei lives on the ground and lower perches. The two species compete, and the more aggressive A. sagrei displaces A. carolinensis from its preferred perches. Where the two species live together, A. carolinensis is restricted to high treetops.

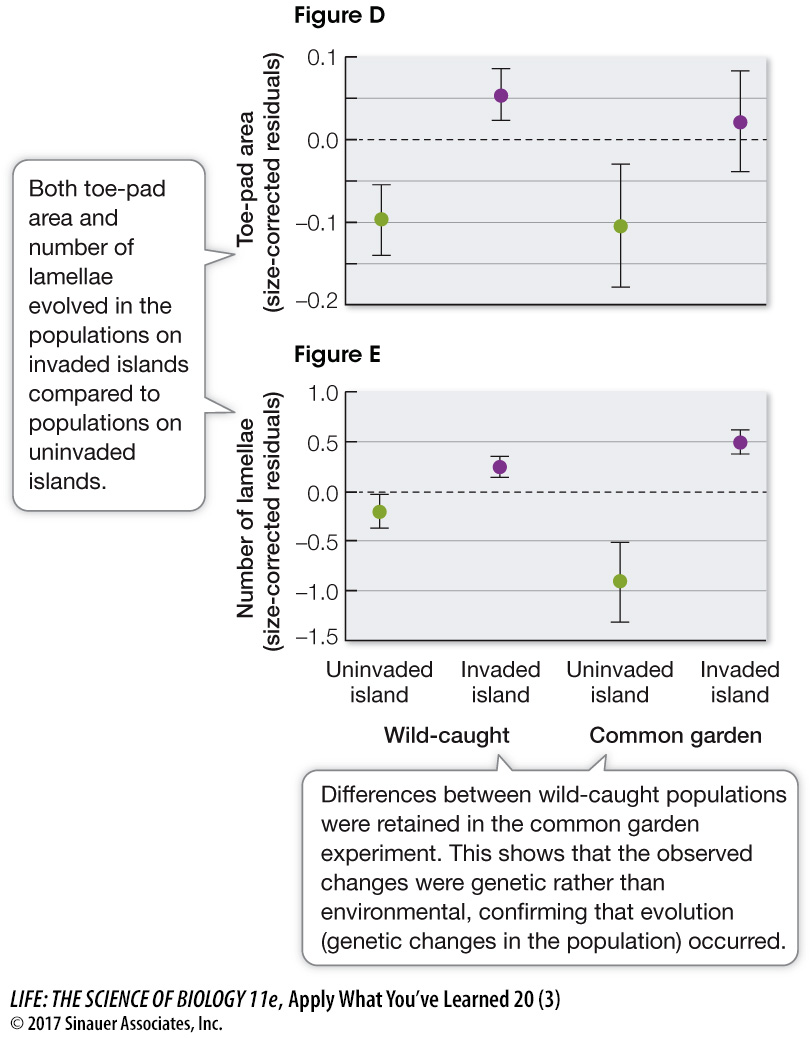

Across species of Anolis, there is a strong association between perch height and the structure of the toe pads that the lizards use to cling to branches (Figure C). Researchers wondered if the shift in perching habitat would lead to rapid evolutionary change in the toe pads of displaced A. carolinensis populations. In 1995, researchers deliberately introduced populations of A. sagrei onto islands that previously supported only populations of A. carolinensis, then followed the evolutionary changes in the lizard populations over the next 15 years. Researchers examined the size of the toe pads, and the number of expanded scales with adhesive bristles (lamellae) on each pad. Other islands continued to support only A. carolinensis.

In 2010, the researchers measured toe-

Questions

1.

What is the evidence for toe-

A. carolinensis from islands with introduced A. sagrei have significantly larger toepads with more lamellae compared to lizards from islands without A. sagrei. As the A. sagrei were only introduced to the islands in 1995, these differences in foot structure appear to have arisen since that time. The fact that the toepads have evolved so quickly indicates that there is strong selection for larger toepads with more lamellae in lizard populations on the invaded islands.

2.

Why was the common garden experiment needed? How would the conclusions of the study have been different if the observed differences in the wild populations were not also evident in the lizards raised in a common, controlled environment?

The common garden experiment confirms that the observed differences have a genetic basis, and are not due to different expression of the same genes on the two sets of islands. If the lizards raised in the common garden experiment had not shown the same level of differences that were observed in the wild populations, then the observed changes could not be attributed to evolution, which refers to genetic changes in populations over time.

3.

Which evolutionary process or processes are most likely to explain the observed evolutionary changes? Which processes do you think are less important, and why?

The most important evolutionary process in this example is selection. Given that tree-

4.

Describe the ways that these populations of A. carolinensis deviate from assumptions of Hardy–

In this case, individuals of A. carolinensis with smaller toepads and fewer lamellae would have an advantage on the ground and on low perches on the invaded islands. Therefore, we would predict that the evolutionary change would occur in the opposite direction; the average toepads would become smaller on the invaded islands compared to un-

Selection for larger toepads appears to be occurring.

Mutation is certainly occurring in the populations (as it does in all species), although it likely has a very small effect at this time scale.

The populations on each island are likely to be fairly small, so drift is occurring.

Gene flow among populations is unknown, but it is likely to be low, since new invasions of islands appear to be rare.

Nonrandom mating among the lizards may be occurring, although there is no evidence of this process described in the experiment.

5.

Instead of A. sagrei, suppose another species of Anolis had been introduced to the Florida islands. Suppose this lizard were an aggressive treetop specialist that excluded A. carolinensis from the highest perches and restricted it to the ground and low perches. In this case, how would you expect the displaced populations of A. carolinensis to have evolved?

The other four processes of evolution (mutation, drift, gene flow, and nonrandom mating) are likely occurring as well, although they are less important to this example:

The variation in toepad size and number of lamellae would not exist without mutations in the genes that produce these structures, so mutation was critical for introducing genetic variation into the populations. But mutations occur very slowly, so very few new mutations that affect toepad size would be expected over 15 years.

Genetic drift is certainly occurring on the islands, because the populations on each island are limited. However, drift would not produce a consistent directional effect in toepad size across islands, and so it cannot account for the consistently larger toepads in A. carolinensis on invaded islands.

There was no attempt to measure gene flow among the islands in this experiment. But the fact that A. sagrei only occurred on islands where it was introduced suggests that inter-

island movement of lizards is low and not likely a major factor in the study. Lizards might choose mates based on their toepad size (non-

random mating), which would affect the distribution of toepad size in the population, producing more variation on which selection could then act. However, there is no evidence for this process in the described experiment.