Several codes of biological nomenclature govern the use of scientific names

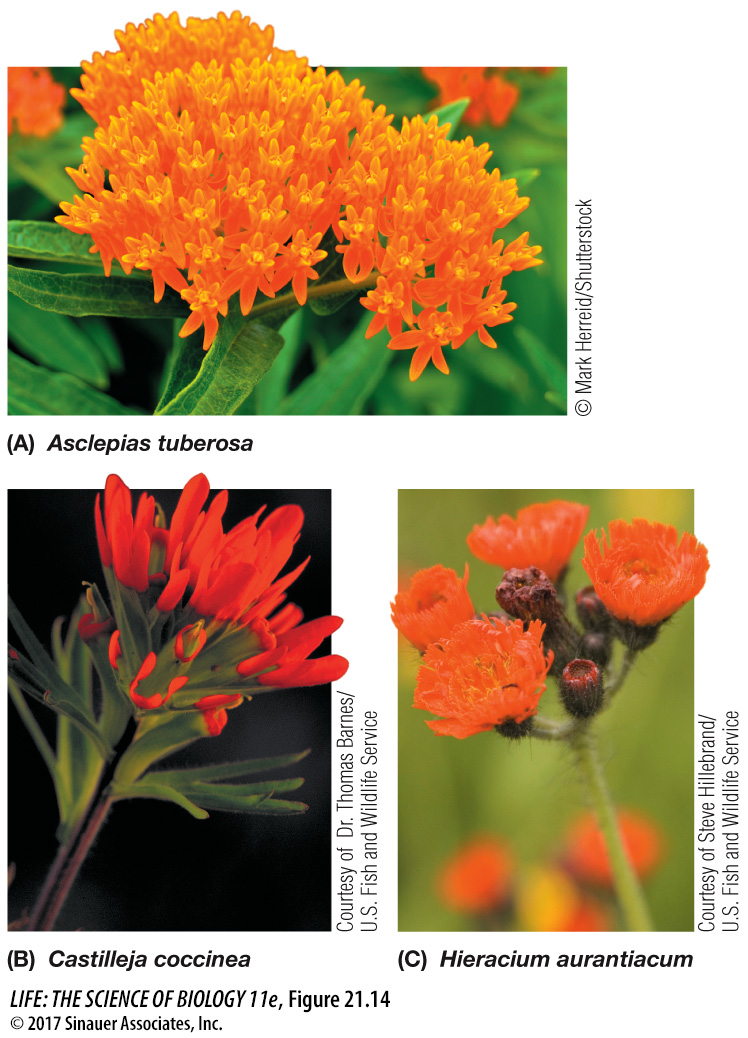

Several sets of explicit rules govern the use of scientific names. Biologists around the world follow these rules voluntarily to facilitate communication and dialogue. There may be dozens of common names for an organism in many different languages, and the same common name may refer to more than one species (Figure 21.14). The rules of biological nomenclature are designed so that there is only one correct scientific name for any single recognized taxon, and (ideally) a given scientific name applies only to a single taxon (that is, each scientific name is unique). Sometimes the same species is named more than once (when more than one taxonomist has taken up the task). In these cases, the rules specify that the valid name is the first name that was proposed. If the same name is inadvertently given to two different species, then the species that was named second must be given a new name.

Because of the historical separation of the fields of zoology, botany (which originally included mycology, the study of fungi), and microbiology, different sets of taxonomic rules were developed for each of these groups. Yet another set of rules emerged later for classifying viruses. This separation of fields resulted in duplicated taxon names in groups governed by the different sets of rules. Drosophila, for example, is both a genus of fruit flies and a genus of fungi, and some species in both groups have identical names. Until recently these duplicated names caused little confusion, since traditionally biologists who studied fruit flies were unlikely to read the literature on fungi (and vice versa). Today, given the prevalence of large, universal biological databases (such as GenBank, which includes DNA sequences from across all life), it is increasingly important that each taxon have a unique and unambiguous name. Biologists are working on a universal code of nomenclature that can be applied to all organisms, so that every species will have a unique identifying name or registration number. This will assist efforts to build an online Encyclopedia of Life that links all the information for all the world’s species.