key concept

21.2

Phylogeny Can Be Reconstructed from Traits of Organisms

key concept

21.2

Phylogeny Can Be Reconstructed from Traits of Organisms

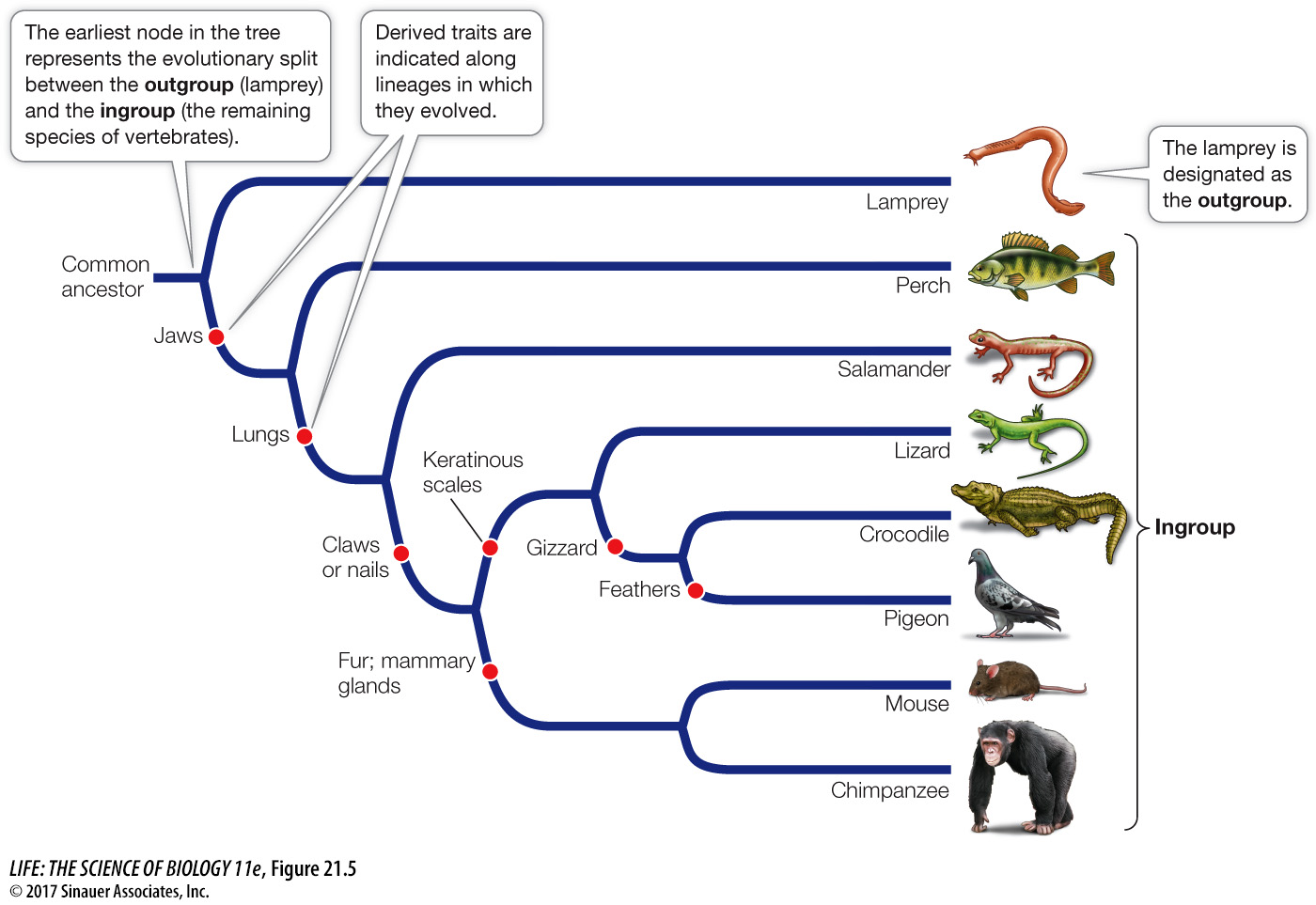

To illustrate how a phylogenetic tree is constructed, consider the eight vertebrate animals listed in Table 21.1: lamprey, perch, salamander, lizard, crocodile, pigeon, mouse, and chimpanzee. We will initially assume that any given derived trait arose only once during the evolution of these animals (that is, there has been no convergent evolution), and that no derived traits were lost from any of the descendant groups (there has been no evolutionary reversal). For simplicity, we have selected traits that are either present (+) or absent (–).

| Taxon | Jaws | Lungs | Claws or nails | Gizzard | Feathers | Fur | Mammary glands | Keratinous scales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamprey (outgroup) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Perch | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Salamander | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lizard | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + |

| Crocodile | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | + |

| Pigeon | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Mouse | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | _ |

| Chimpanzee | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | _ |

focus your learning

Modern phylogenetic methods employ the principle of parsimony and mathematical models (when appropriate) to analyze morphological, developmental, paleontological, behavioral, and molecular data.

In a phylogenetic study, the group of organisms of primary interest is called the ingroup. As a point of reference, an ingroup is compared with an outgroup: a species or group that is closely related to the ingroup but is known to be phylogenetically outside it. In other words, the root of the tree is located between the ingroup and the outgroup. Any trait that is present in both the ingroup and the outgroup must have evolved before the origin of the ingroup and thus must be ancestral for the ingroup. In contrast, traits that are present in only some members of the ingroup must be derived traits within that ingroup. As we will see in Chapter 32, a group of jawless fish called the lampreys is thought to have separated from the lineage leading to the other vertebrates before the jaw arose. Therefore we have included the lamprey as the outgroup for our analysis. Because derived traits are traits acquired by other members of the vertebrate lineage after they diverged from the outgroup, any trait that is present in both the lamprey and the other vertebrates is judged to be ancestral.

We begin by noting that the chimpanzee and mouse share two traits—

Table 21.1 also tells us that, among the animals in our ingroup, the pigeon has a unique trait: feathers. Feathers are a synapomorphy of birds and their extinct relatives. However, because we only have one bird in this example, the presence of feathers provides no clues concerning relationships among these eight species of vertebrates. However, gizzards are found in both birds and crocodiles, so this trait is evidence of a close relationship between birds and crocodilians.

By combining information about the various synapomorphies, we can construct a phylogenetic tree. We infer from our information that mice and chimpanzees—

Figure 21.5 shows a phylogenetic tree for the vertebrates in Table 21.1, based on the shared derived traits we examined. This particular tree was easy to construct because it is based on a very small sample of traits, and the derived traits we examined evolved only once and were never lost after they appeared. Had we included a snake in the group, our analysis would not have been as straightforward. We would have needed to examine additional characters to determine that snakes evolved from a group of lizards that had limbs. In fact, the analysis of many characters shows that snakes evolved from burrowing lizards that became adapted to a subterranean existence.

Activity 21.1 Constructing a Phylogenetic Tree