We can recognize many species by their appearance

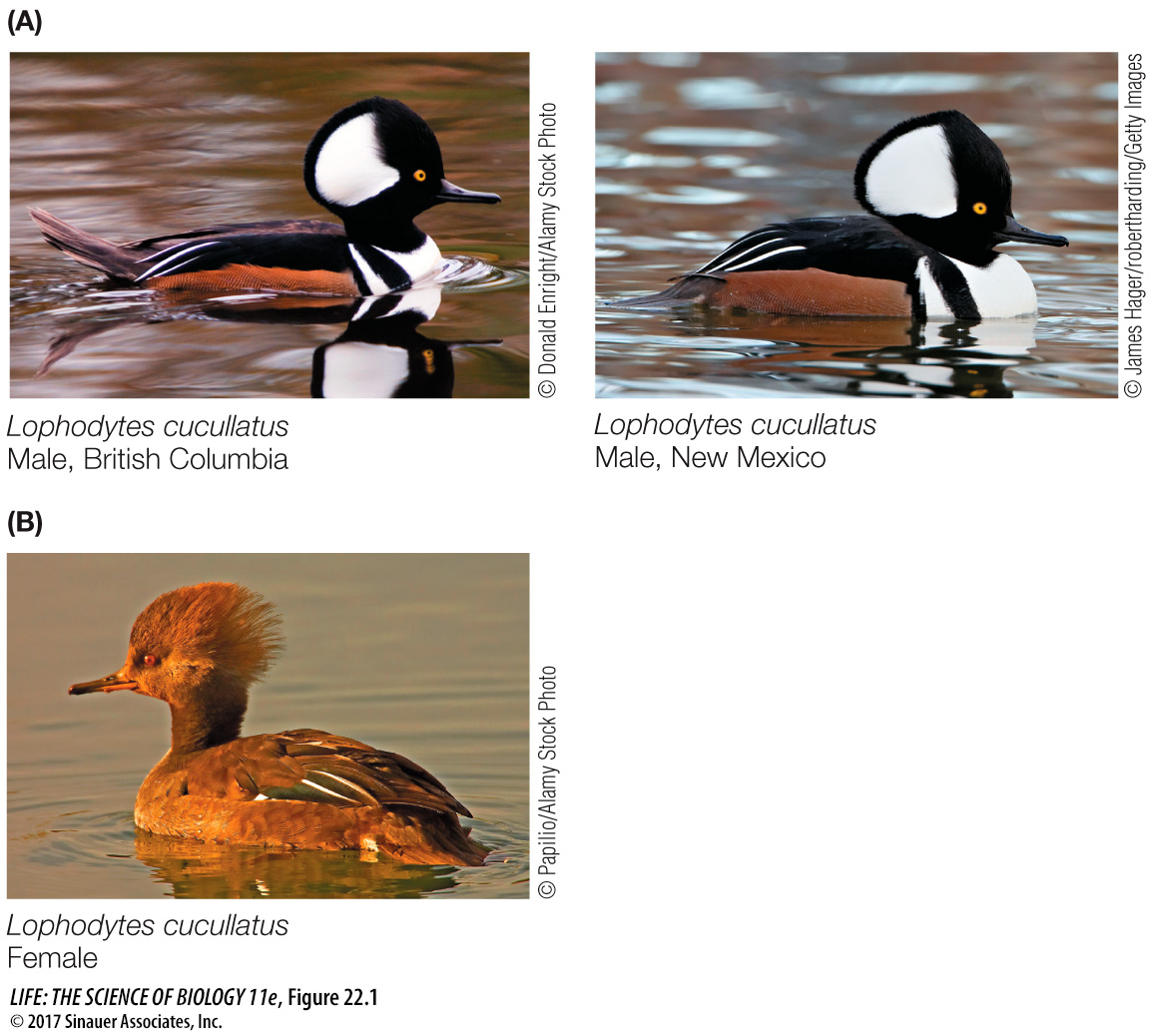

Someone who is knowledgeable about a group of organisms, such as birds or flowering plants, can usually distinguish the different species found in a particular area simply by looking at them. Standard field guides to birds, mammals, insects, and wildflowers are possible only because many species change little in appearance over large geographic distances (Figure 22.1A).

More than 250 years ago, Carolus Linnaeus developed the system of binomial nomenclature by which species are named today (see Key Concept 21.4). Linnaeus described and named thousands of species, but because he knew nothing about the genetics or the mating behavior of the organisms he was naming, he classified them on the basis of their appearance alone. In other words, Linnaeus used a morphological species concept, a construct that assumes that a species comprises individuals that “look alike” and that individuals that do not look alike belong to different species. Although Linnaeus could not have known it, the members of most of the groups he classified as species look alike because they share many alleles of the genes that code for their morphological features.

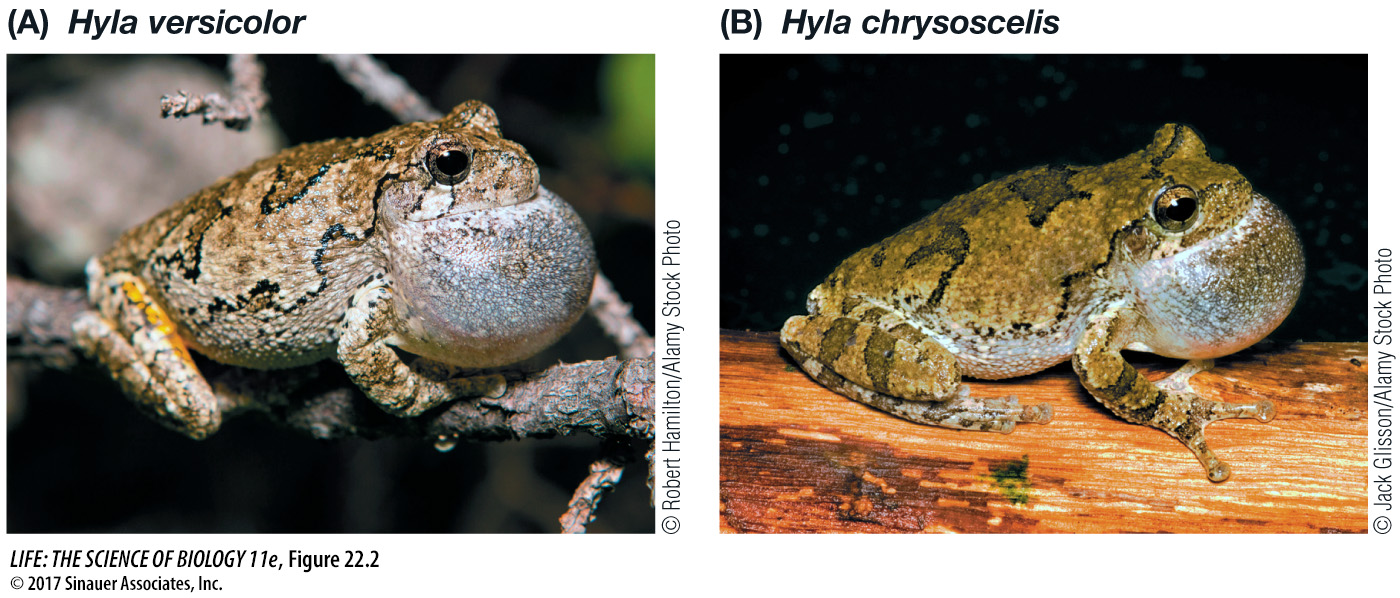

Using morphology to define species has limitations. Members of the same species do not always look alike. For example, males, females, and young individuals do not always resemble one another closely (Figure 22.1B). Furthermore, morphology is of little use in the case of cryptic species—