Extraterrestrial events have triggered changes on Earth

At least 30 meteorites of sizes between tennis and soccer balls strike Earth each year. Collisions with larger meteorites or comets are rare, but such collisions have probably been responsible for several mass extinctions. Several types of evidence tell us about these collisions. Their craters, and the dramatically disfigured rocks that result from their impact, are found in many places. Geologists have discovered compounds in these rocks that contain helium and argon with isotope ratios characteristic of meteorites, which are very different from the ratios found elsewhere on Earth.

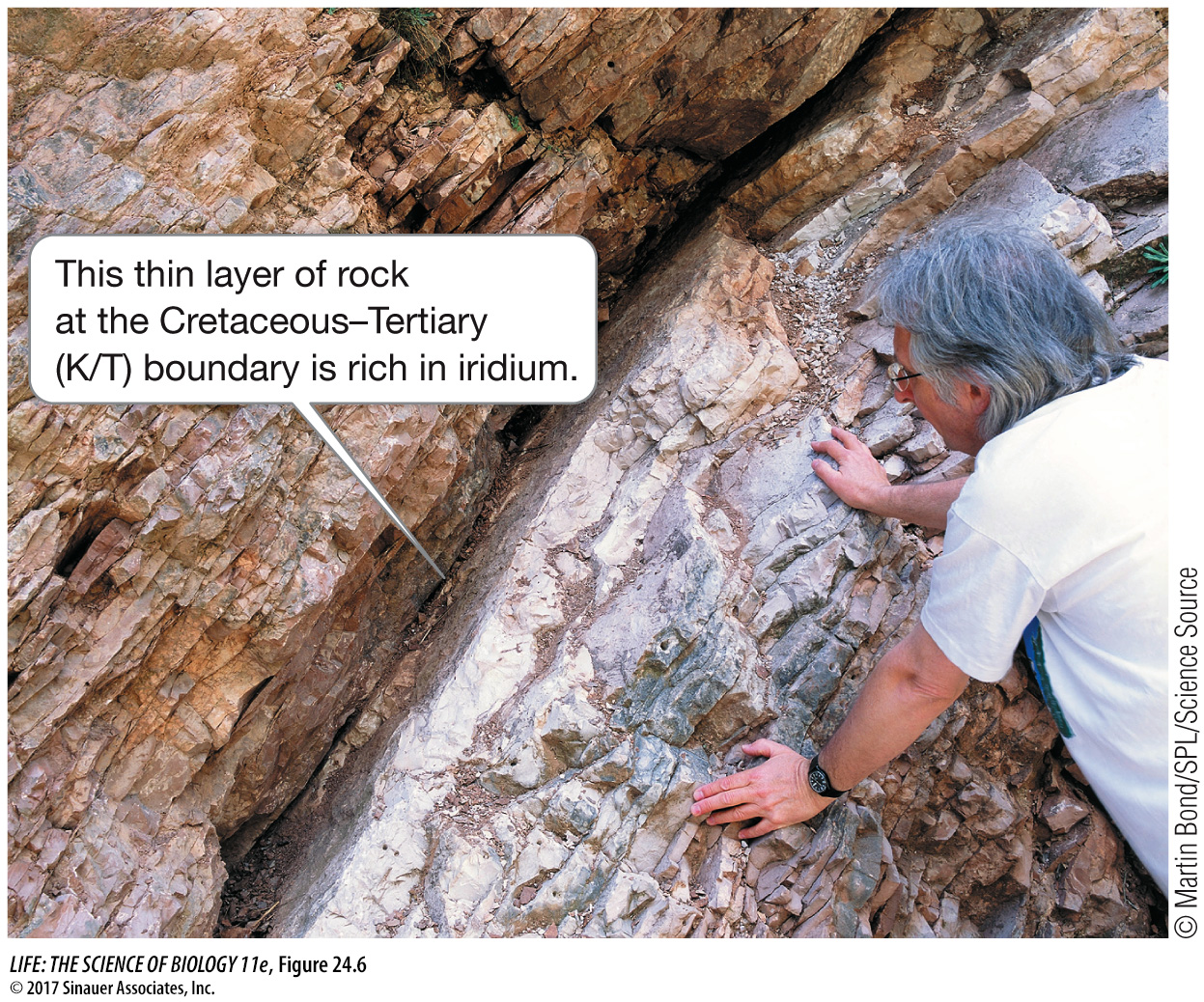

A meteorite caused or contributed to a mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period (about 65.5 mya). The first clue that a meteorite was responsible came from the abnormally high concentrations of the element iridium found in a thin layer separating rocks deposited during the Cretaceous from rocks deposited during the Tertiary (Figure 24.6). Iridium is abundant in some meteorites, but it is exceedingly rare on Earth’s surface. When scientists discovered a circular crater 180 km in diameter buried beneath the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, they constructed the following scenario. When it collided with Earth, the meterorite released energy equivalent to that of 100 million megatons of high explosives, creating great tsunamis. A massive plume of debris rose into the atmosphere, spread around Earth, and descended. The descending debris heated the atmosphere to several hundred degrees and ignited massive fires. It also blocked the sun, preventing plants from photosynthesizing. The settling debris formed the iridium-