Microbiomes are critical to the health of many eukaryotes

Although only a few bacterial species are pathogens, popular notions of bacteria as “germs” and fear of the consequences of infection cause many people to assume that most bacteria are harmful. Increasingly, however, biologists are discovering that the health of humans (as well as that of most other eukaryotes) depends in large part on the health of our microbiomes: the communities of bacteria and prokaryotic archaea that live in and on our bodies. Other communities of microbes live in close association with other multicellular organisms.

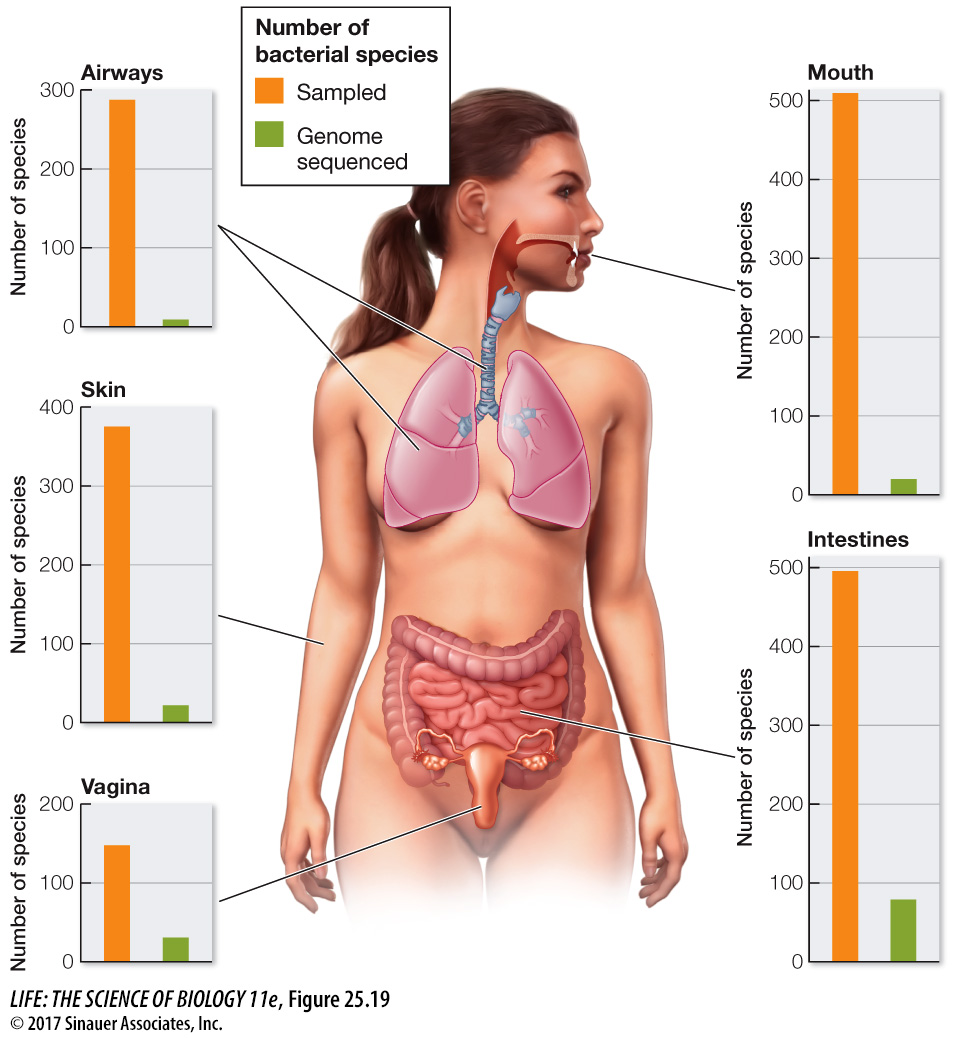

Every surface of your body is covered with diverse communities of bacteria (Figure 25.19). A recent study identified more than 1,000 species of bacteria that live on human skin. Inside your body, your digestive system teems with bacteria. When these communities are disrupted, they must be restored before the body can function normally.

investigating life

How Do Bacteria Communicate with One Another?

experiment

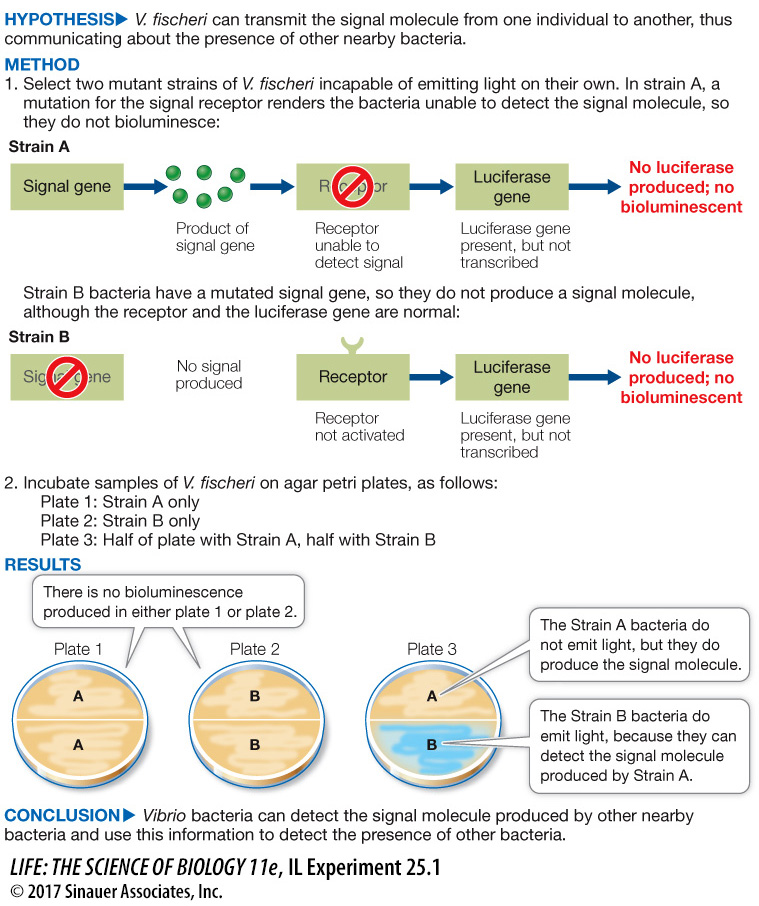

Original Paper: Miller, M. B. and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology 55:165–

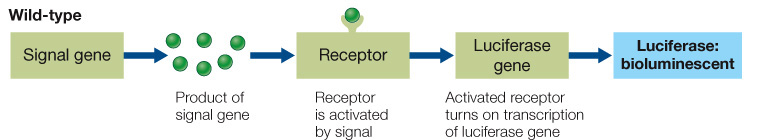

Bonnie Bassler and her colleagues at Princeton University investigated how Vibrio fischeri bacteria communicate with one another. These bacteria produce bioluminescence when they are present in sufficiently high densities. In a normal V. fischeri bacterium, the following pathway produces bioluminescence when a bacterial colony becomes dense enough to produce sufficient signal:

The fact that the bacteria emit light only when they are present in high densities suggests that the signal is used to communicate among nearby bacteria, alerting one another to their presence. But how can we tell that the signal produced by one bacterium is being received by another?

Biologists are discovering that many complex health problems are linked to the disruption of our microbiomes. These diverse microbial communities affect the expression of our genes and play a critical role in the development and maintenance of a healthy immune system. When our microbiomes contain an appropriate community of beneficial species, our bodies function normally. But these communities are strongly affected by our life experiences, by the food we eat, by the medicines we take, and by our exposure to various environmental toxins. The recent rapid increase in the rate of autoimmune diseases in humans—

The early acquisition of an appropriate microbiome is critical for lifelong health. Normally, a human infant acquires much of its microbiome at birth, from the microbiome in its mother’s vagina. Other components of the microbiome are also acquired from the mother, especially through breast feeding. Recent studies have shown that babies born by cesarean section, as well as babies that are bottle-

Humans use some of the metabolic products—

Animals harbor a variety of microbes in their digestive tracts, many of which play important roles in digestion. Cattle depend on prokaryotes to break down plant material. Like most animals, cattle cannot produce cellulase, the enzyme needed to start the digestion of the cellulose that makes up the bulk of their plant food. However, bacteria living in a special section of the gut, called the rumen, produce enough cellulase to process the daily diet for the cattle.