A small minority of bacteria are pathogens

The late nineteenth century was a productive era in the history of medicine—

The microorganism is always found in individuals with the disease.

The microorganism can be taken from the host and grown in pure culture.

A sample of the culture produces the same disease when injected into a new, healthy host.

The newly infected host yields a new, pure culture of microorganisms identical to those obtained in the second step.

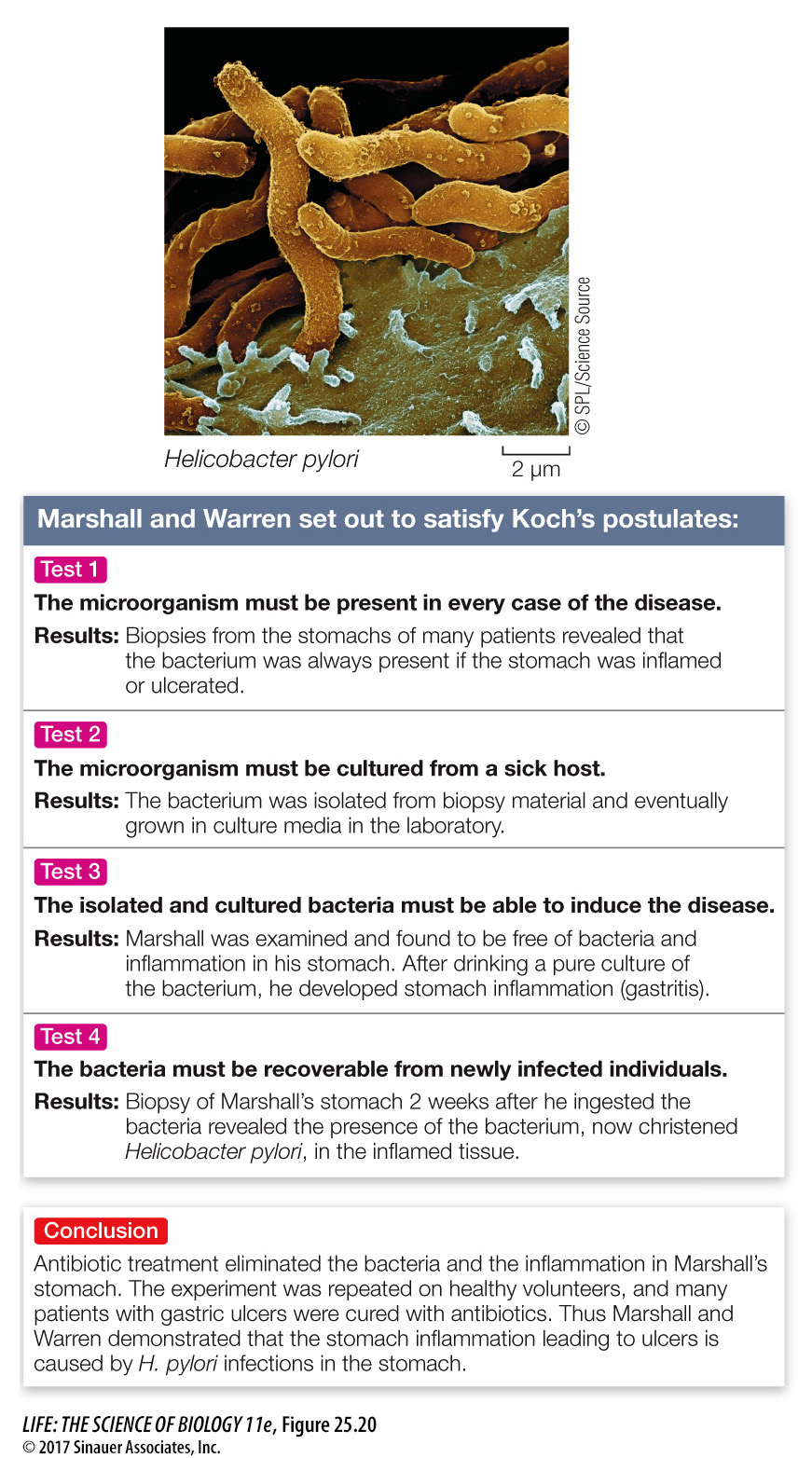

These rules, called Koch’s postulates, were important tools in a time when it was not widely understood that microorganisms cause disease. Although modern medical science has more powerful diagnostic tools, Koch’s postulates remain useful. For example, physicians were taken aback in the 1980s when stomach ulcers—

For an organism to be a successful pathogen, it must:

arrive at the body surface of a potential host;

enter the host’s body;

evade the host’s defenses;

reproduce inside the host; and

infect a new host.

Failure to complete any of these steps ends the disease cycle of a pathogenic organism. Yet in spite of the many defenses available to potential hosts, some bacteria are very successful pathogens. Pathogenic bacteria are often surprisingly difficult to combat, even with today’s arsenal of antibiotics. One source of this difficulty is their ability to form biofilms.

For the host, the consequences of a bacterial infection depend on several factors. One is the invasiveness of the pathogen: its ability to multiply in the host’s body. Another is its toxigenicity: its ability to produce toxins (chemical substances that are harmful to the host’s tissues). Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the agent that causes diphtheria, has low invasiveness and multiplies only in the throat, but its toxigenicity is so great that the entire body is affected. In contrast, Bacillus anthracis, which causes anthrax, has low toxigenicity but is so invasive that the entire bloodstream ultimately teems with the bacteria.

There are two general types of bacterial toxins: exotoxins and endotoxins. Endotoxins are released when certain bacteria grow or lyse (burst). Endotoxins are lipopolysaccharides (complexes consisting of a polysaccharide and a lipid component) that form part of the outer bacterial membrane. Endotoxins are rarely fatal to the host; they normally cause fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. Among the endotoxin producers are some strains of the proteobacteria Salmonella and Escherichia.

Exotoxins are soluble proteins released by living, multiplying bacteria. They are highly toxic—