key concept

26.2

Major Lineages of Eukaryotes Diversified in the Precambrian

key concept

26.2

Major Lineages of Eukaryotes Diversified in the Precambrian

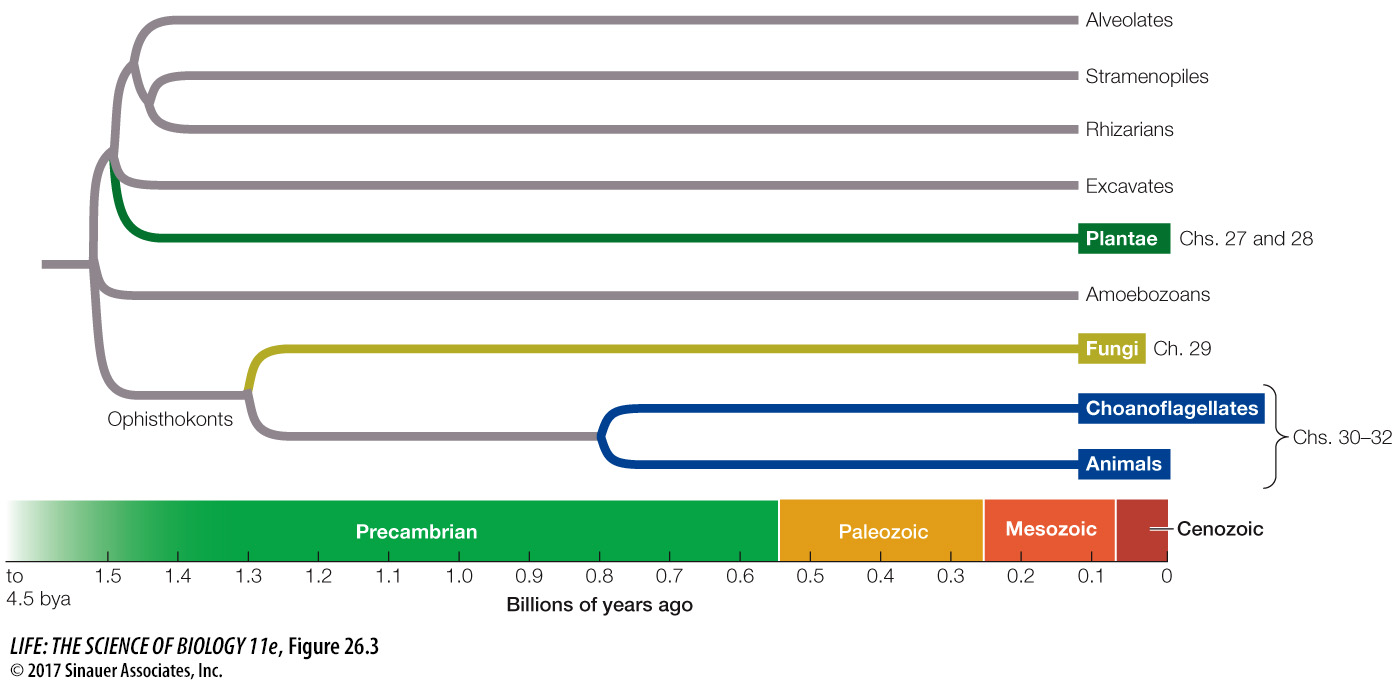

Most eukaryotes can be placed in one of eight major clades that began to diversify about 1.5 billion years ago: alveolates, stramenopiles, rhizarians, excavates, plants, amoebozoans, fungi, and animals (Figure 26.3). Plants, fungi, and animals each have close protist relatives (such as the choanoflagellate relatives of animals), which we will discuss along with those major multicellular eukaryote groups in Chapters 27–32.

focus your learning

Multicellularity evolved dozens of times in the evolutionary history of eukaryotes.

Dinoflagellates are important primary producers of aquatic organic matter.

Apicomplexans possess an apical complex.

Ciliates are named for their numerous hair-

like cilia. Stramenopiles include the diatoms, the brown algae, and the oomycetes.

Brown algae are multicellular stramenopiles that have an abundance of fucoxanthin in their chloroplasts.

Rhizarians include the cercozoans, foraminiferans, and radiolarians.

A single amoeboid cell is the vegetative unit of the cellular slime mold.

Many protists are medically or economically important.

Each of the five major groups of protist eukaryotes covered in this chapter consists of organisms with enormously diverse body forms and nutritional lifestyles. Some protists are motile, whereas others do not move. Some protists are photosynthetic, whereas others are heterotrophic. Most protists are unicellular, but some are multicellular. Most protists are microscopic, but a few are huge (giant kelps, for example, can grow to half the length of a football field). We refer to the unicellular species of protists as microbial eukaryotes, but keep in mind that there are large, multicellular protists as well.

Multicellularity has arisen dozens of times across the evolutionary history of eukaryotes. Four of the origins of multicellularity resulted in large organisms that are familiar to most people: plants, animals, fungi, and brown algae (the last are a group of stramenopiles). In addition, there are dozens of smaller and less familiar groups among the eukaryotes that include multicellular species. Recent experimental studies have shown that artificial selection for multicellularity can produce repeated, convergent evolution of multicellular forms over just a few months in some normally unicellular eukaryotic species. In addition, many unicellular species retain individual identities but nonetheless associate in large multicellular colonies. There is a near-

Biologists used to classify protists largely on the basis of their life histories and reproductive features. In recent years, however, electron microscopy and gene sequencing have revealed many new patterns of evolutionary relatedness among these groups. Analyses of slowly evolving gene sequences are making it possible to explore evolutionary relationships among eukaryotes in ever greater detail and with greater confidence. Nonetheless, some substantial areas of uncertainty remain, and lateral gene transfer may complicate efforts to reconstruct the evolutionary history of protists (as was also true for prokaryotes; see Key Concept 25.1). Today we recognize great diversity among the many distantly related protist clades.