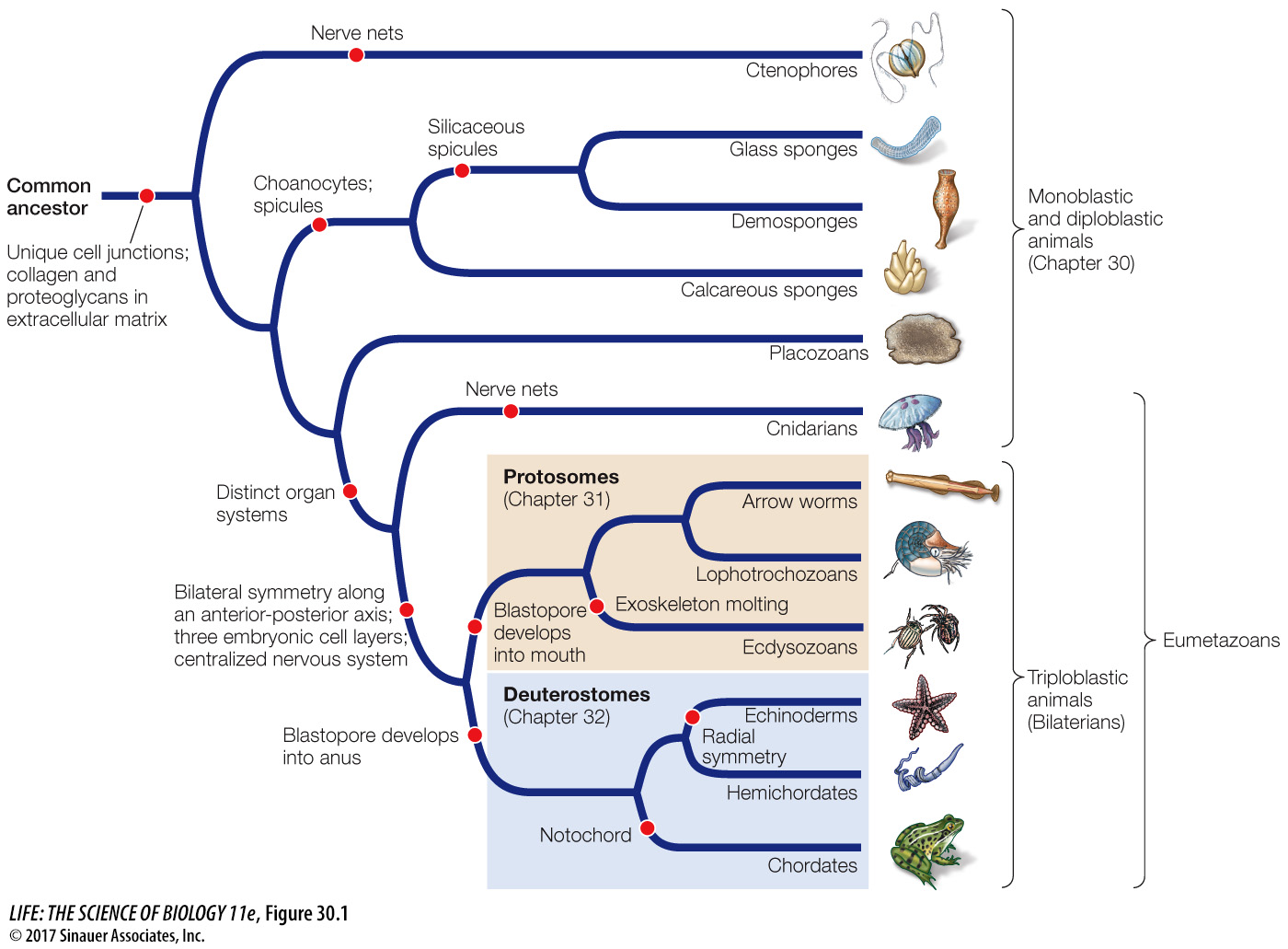

Animal monophyly is supported by gene sequences and morphology

The most convincing evidence that all the organisms considered to be animals share a common ancestor comes from phylogenetic analyses of their gene sequences. Relatively few complete animal genomes are available, but more are being sequenced each year. Analyses of these genomes, as well as of many individual gene sequences, have shown that the animals are indeed monophyletic. The best-

Q: Based on this tree, which of the depicted traits evolved multiple times among animals, and in which lineages?

Nervous systems are shown evolving three times: nerve nets in ctenophores and in cnidarians, and central nervous systems in bilaterians.

| Group | Approximate number of living species described | Major subgroups, other names, and notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ctenophores | 250 | Comb jellies |

| Sponges | 8,500 | Demosponges, glass sponges, calcareous sponges |

| Placozoans | 2 | Additional species have been discovered but not yet formally named |

| Cnidarians | 12,500 |

Anthozoans: Corals, sea anemones Hydrozoans: Hydras and hydroids Scyphozoans: Jellyfish Myxozoans: Parasitic mucous animals; sometimes placed in group distinct from cnidarians |

| Orthonectids | 45 | Microscopic wormlike parasites of marine invertebrates; relationships uncertain |

| Rhombozoans | 125 | Tiny (0.5– |

| PROTOSTOMES | ||

| Arrow worms | 180 | Glass worms |

| Lophotrochozoans | ||

| Bryozoans | 5,500 | Moss animals |

| Entoprocts | 170 | Sessile aquatic animals, 0.1– |

| Flatworms | 30,000 | Free- |

| Gastrotrichs | 800 | “Hairy backs” |

| Rotifers and relatives | 3,000 | Rotifers, spiny- |

| Ribbon worms | 1,200 | Proboscis worms |

| Phoronids | 10 | Sessile marine filter feeders |

| Brachiopods | 450 | Lampshells |

| Annelids | 19,000 |

Polychaetes (generally marine; may not be monophyletic) Clitellates: earthworms, freshwater worms, leeches |

| Mollusks | 117,000 |

Monoplacophorans Chitons Bivalves: Clams, oysters, mussels Gastropods: Snails, slugs, limpets Cephalopods: Squid, octopuses, nautiloids |

| Ecdysozoans | ||

| Kinorhynchs | 180 | Mud dragons |

| Loriciferans | 30 | Brush heads |

| Priapulids | 20 | Penis worms |

| Nematodes | 25,000 | Roundworms |

| Horsehair worms | 350 | Gordian worms |

| Onychophorans | 180 | Velvet worms |

| Tardigrades | 1,200 | Water bears |

| Arthropods | ||

| Chelicerates | 114,000 | Horseshoe crabs, pycnogonids, and arachnids (scorpions, harvestmen, spiders, mites, ticks) |

| Myriapods | 12,000 | Millipedes, centipedes |

| Crustaceans | 67,000 | Crabs, shrimps, lobsters and crayfish, barnacles, copepods |

| Hexapods | 1,020,000 | Insects and their wingless relatives |

| DEUTEROSTOMES | ||

| Xenoturbellids | 5 | Secondarily simple marine worms; relationships uncertain |

| Acoels | 400 | Very small (mostly <2 mm) flattened marine worms; relationships uncertain |

| Echinoderms | 7,500 | Crinoids (sea lilies and feather stars), brittle stars, sea stars, sea daisies, sea urchins, sea cucumbers |

| Hemichordates | 120 | Acorn worms and pterobranchs |

| Tunicates | 2,800 | Sea squirts (ascidians), salps, and larvaceans |

| Lancelets | 35 | Cephalochordates |

| Vertebrates | 65,000 | Hagfish, lampreys, cartilaginous fish, ray- |

Although animals were considered to belong to a single clade long before gene sequencing became possible, surprisingly few morphological features are shared across all species of animals. Two morphological synapomorphies have been identified that distinguish the animals:

A common set of extracellular matrix molecules, including collagen and proteoglycans (see Figure 5.22)

Unique types of junctions between cells (tight junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions; see Figure 6.7)

Although some animals in a few groups lack one or the other of these traits, it is believed that these traits were possessed by the ancestor of all animals and subsequently lost in those groups. Similarities among animals in the organization and function of Hox and other developmental genes (see Chapter 19) provide additional evidence of developmental mechanisms shared by a common animal ancestor.

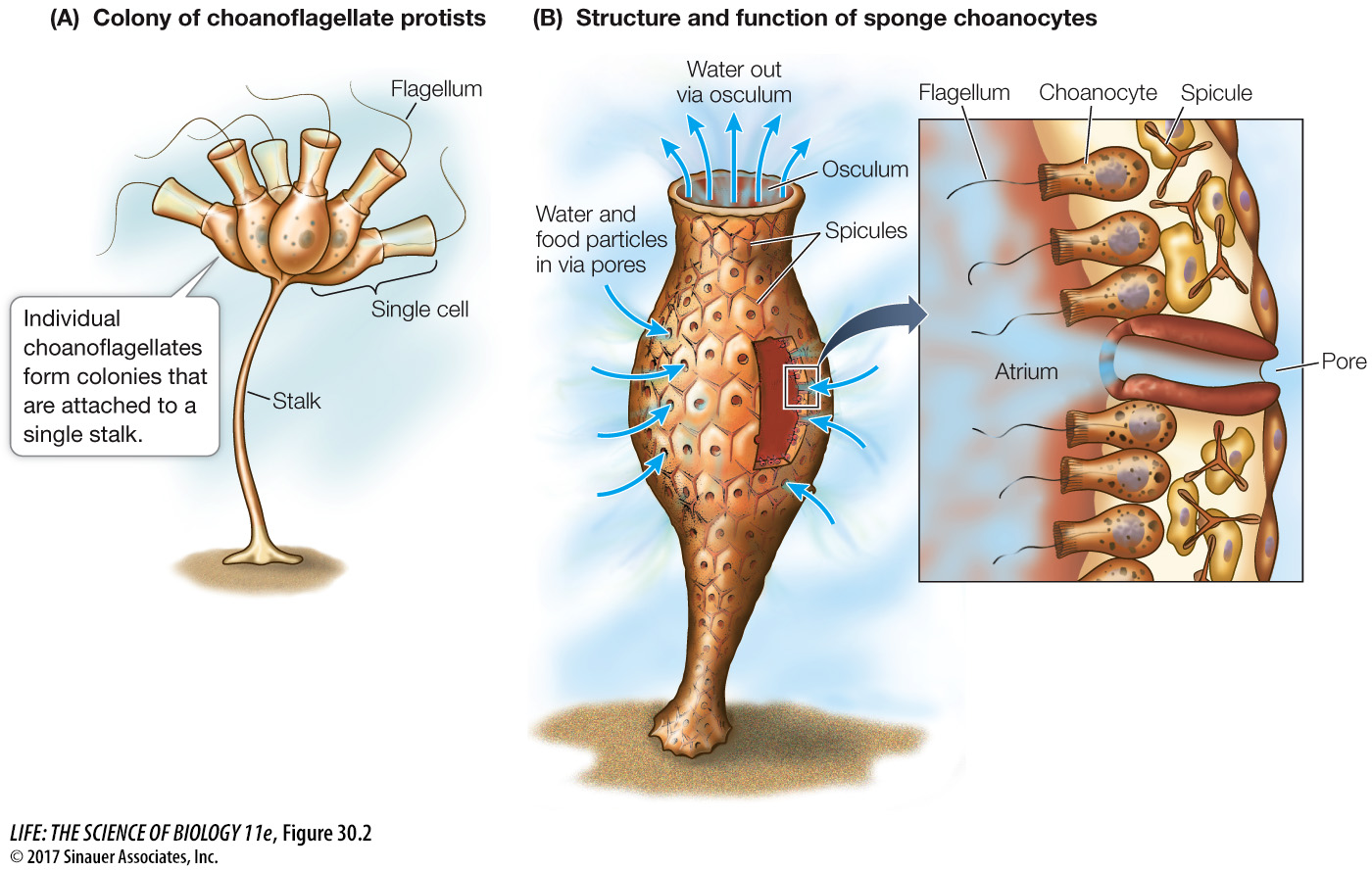

The common ancestor of animals was likely a colonial flagellated protist similar to existing colonial choanoflagellates. Choanoflagellate colonies have clearly retained similarities to the multicellular sponges (Figure 30.2). Why did early animals begin to form multicellular colonies? One hypothesis is that multicellular colonies are more efficient than single cells are at capturing their prey. Experiments with living species of choanoflagellates show that they spontaneously form multicellular colonies in response to signaling compounds that are found on certain species of planktonic bacteria they eat (Figure 30.3).

One hypothesis of animal origins postulates a choanoflagellate-

Nearly 80 percent of the 1.8 million named species of living organisms are animals, and millions of additional animal species await discovery (see Chapter 31 opening story). Evidence for the evolutionary relationships among animal groups can be found in fossils, in patterns of embryonic development, in the morphology and physiology of living animals, in the structure of animal proteins, and in gene sequences. Increasingly, studies of the phylogenetic relationships among major animal groups have come to depend on genomic sequence comparisons.