Most animals are symmetrical

The overall shape of an animal can be described by its symmetry. An animal is said to be symmetrical if it can be divided along at least one plane into similar halves. Animals that have no plane of symmetry are said to be asymmetrical. Placozoans and many sponges are asymmetrical, but most other animals have some kind of symmetry, which is governed by the expression of regulatory genes during development.

The simplest form of symmetry is spherical symmetry, in which body parts radiate out from a central point. An infinite number of planes passing through the central point can divide a spherically symmetrical organism into similar halves. Spherical symmetry is widespread among unicellular protists, but most animals possess other forms of symmetry.

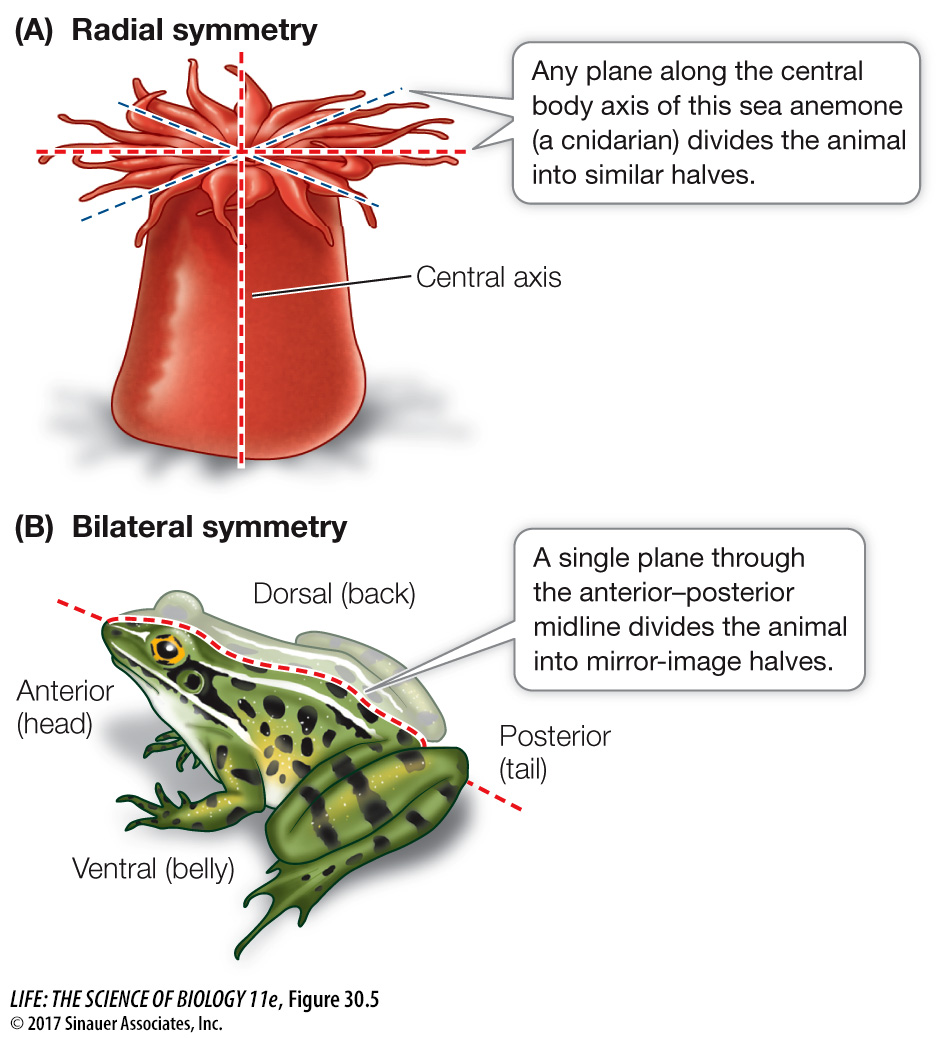

In organisms with radial symmetry, body parts are arranged around one main axis at the body’s center (Figure 30.5A). Ctenophores (comb jellies) are radially symmetrical, as are many cnidarians (such as sea anemones and jellyfish) and echinoderms. A perfectly radially symmetrical animal can be divided into similar halves by any plane that contains the main axis. However, most radially symmetrical animals—

Bilateral symmetry is characteristic of animals that have a distinct front end, which typically precedes the rest of the body as the animal moves. A bilaterally symmetrical animal can be divided into mirror-

Bilateral symmetry is strongly correlated with cephalization (Greek kephalos, “head”), which is the concentration of sensory organs and nervous tissues at the anterior end of the animal. Cephalization has been favored by natural selection because the anterior end of a bilaterally symmetrical animal typically encounters new environments first.