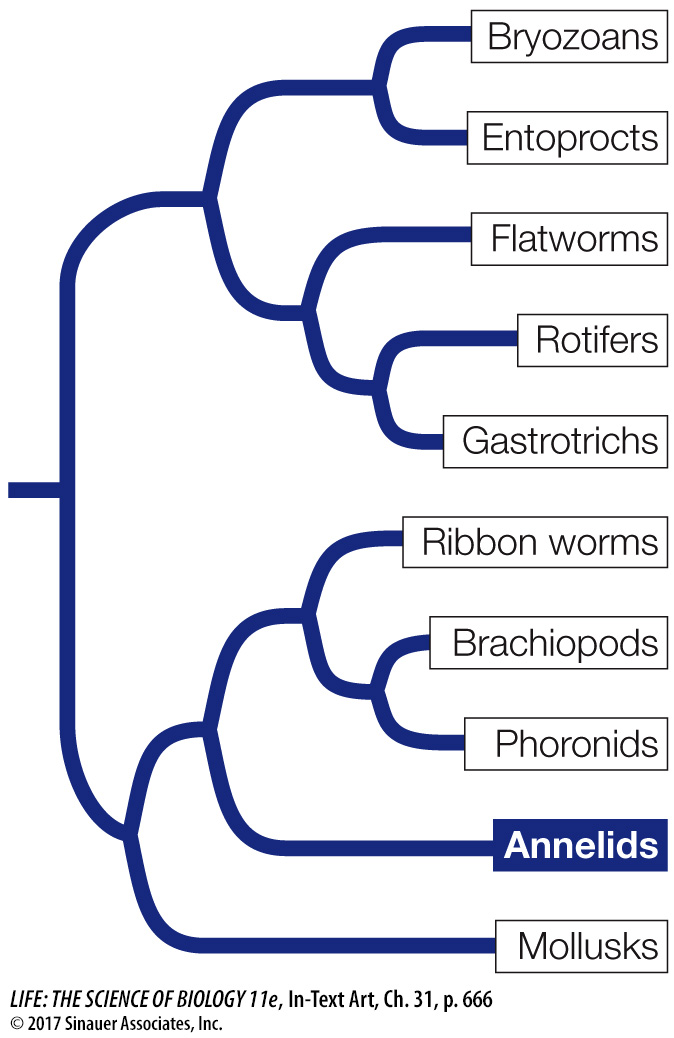

Annelids have segmented bodies

The wormlike bodies of annelids are clearly segmented. As described in Key Concept 30.2, segmentation allows an animal to move different parts of its body independently, giving it much better control of its movement. The earliest segmented worms, preserved as fossils from the middle Cambrian, were burrowing marine annelids.

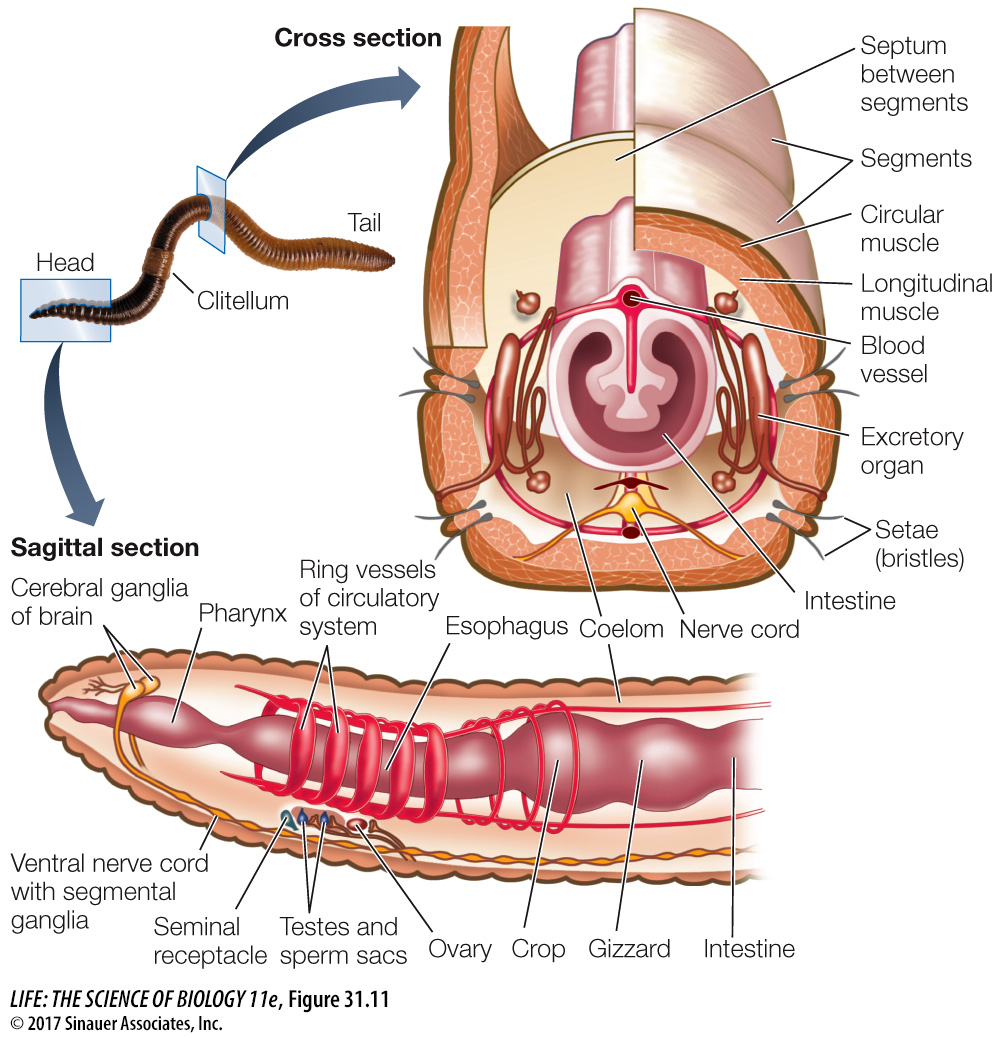

In most large annelids, the coelom in each segment is isolated from those in other segments (Figure 31.11). A separate nerve center called a ganglion (plural ganglia) controls each segment; nerve cords that connect the ganglia coordinate their functioning. Most annelids lack a rigid external protective covering; instead they have a thin, permeable body wall that serves as a general surface for gas exchange. Most annelids are thus restricted to moist environments because they lose body water rapidly in dry air. The approximately 19,000 described species live in marine, freshwater, and moist terrestrial environments.

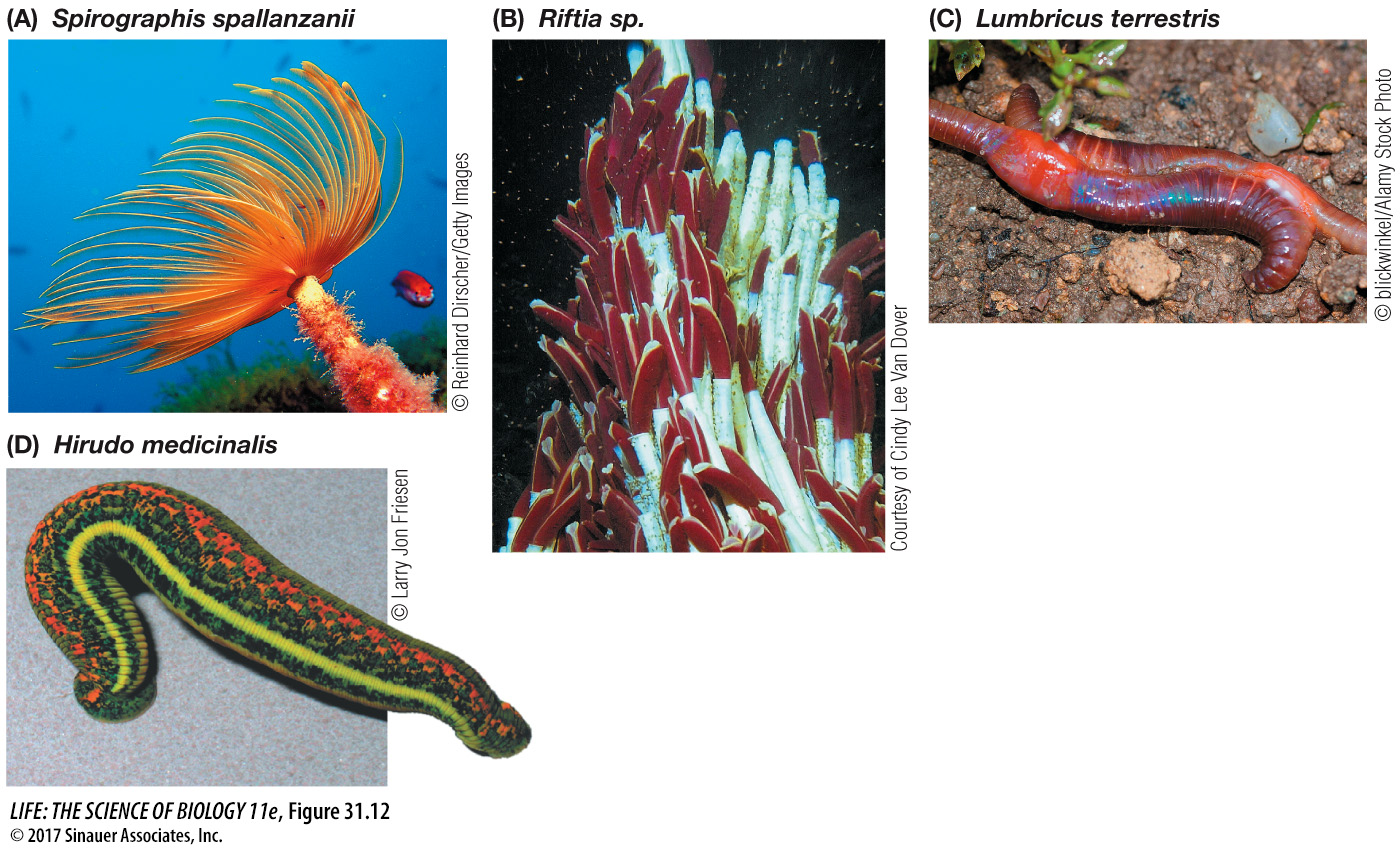

POLYCHAETES More than half of all annelid species are commonly known as polychaetes (“many hairs”), although this is a descriptive term rather than the name of a single clade. Recent molecular studies indicate that polychaetes are paraphyletic with respect to the remaining annelids. Most polychaetes are marine, and many live in burrows in soft sediments. Most of them have one or more pairs of eyes and one or more pairs of tentacles, with which they capture prey or filter food from the surrounding water, at the anterior end of the body (Figure 31.12A; see also Figure 30.7A). In some species, the body wall of most segments extends laterally as a series of thin outgrowths called parapodia. The parapodia function in gas exchange, and some species use them to move. Stiff bristles called setae protrude from each parapodium, forming temporary contact with the substrate and preventing the animal from slipping backward when its muscles contract.

Members of one polychaete clade, the pogonophorans, secrete tubes made of chitin and other substances, in which they live (Figure 31.12B). Pogonophorans have lost their digestive tract (they have no mouth or gut). So how do they obtain nutrition? Part of the answer is that pogonophorans can take up dissolved organic matter directly from the sediments in which they live or from the surrounding water. Much of their nutrition, however, is provided by endosymbiotic bacteria that the pogonophorans house in a specialized organ known as the trophosome. These bacteria oxidize hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur-

Pogonophorans were not discovered until early in the twentieth century, when the first species were discovered on the seafloor at depths of up to a few hundred meters. In recent decades, deep-

CLITELLATES The approximately 3,000 described species of clitellates, which form a well-

Oligochaetes (“few hairs”) have no parapodia, eyes, or anterior tentacles, and they have only four pairs of setae bundles per segment. Earthworms—

Leeches, like oligochaetes, lack parapodia and tentacles. The coelom of leeches is not divided into compartments; the coelomic space is largely filled with undifferentiated tissue. Groups of segments at each end of the body are modified to form suckers, which serve as temporary anchors that aid the leech in its movement. With its posterior sucker attached to a substrate, the leech extends its body by contracting its circular muscles. The anterior sucker is then attached, the posterior one detached, and the leech shortens itself by contracting its longitudinal muscles. Leeches live in freshwater or terrestrial habitats.

Most leeches are ectoparasites that feed by making an incision in a host, from which blood flows. A leech can ingest so much blood in a single feeding that its body may enlarge severalfold. The leech secretes an anticoagulant into the wound that keeps the host’s blood flowing. For centuries, medical practitioners employed leeches to draw blood to treat diseases they believed were caused by an excess of blood or by “bad blood.” Although most leeching practices (such as inserting a leech in a person’s throat to alleviate swollen tonsils) have been abandoned, Hirudo medicinalis (the medicinal leech; Figure 31.12D) is used today to reduce fluid pressure and prevent blood clotting in damaged tissues, to eliminate pools of coagulated blood, and to prevent scarring. The anticoagulants of certain other leech species also contain anesthetics and blood vessel dilators and are being studied for possible medical uses.

Media Clip 31.5 Leeches Feeding on Blood