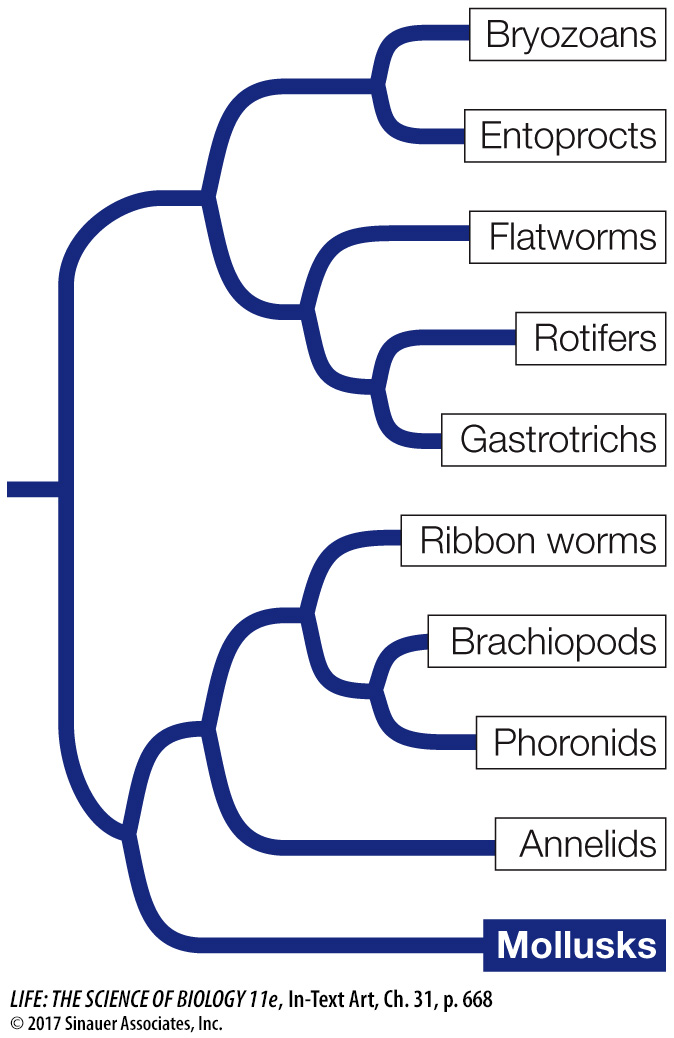

Mollusks have undergone a dramatic evolutionary radiation

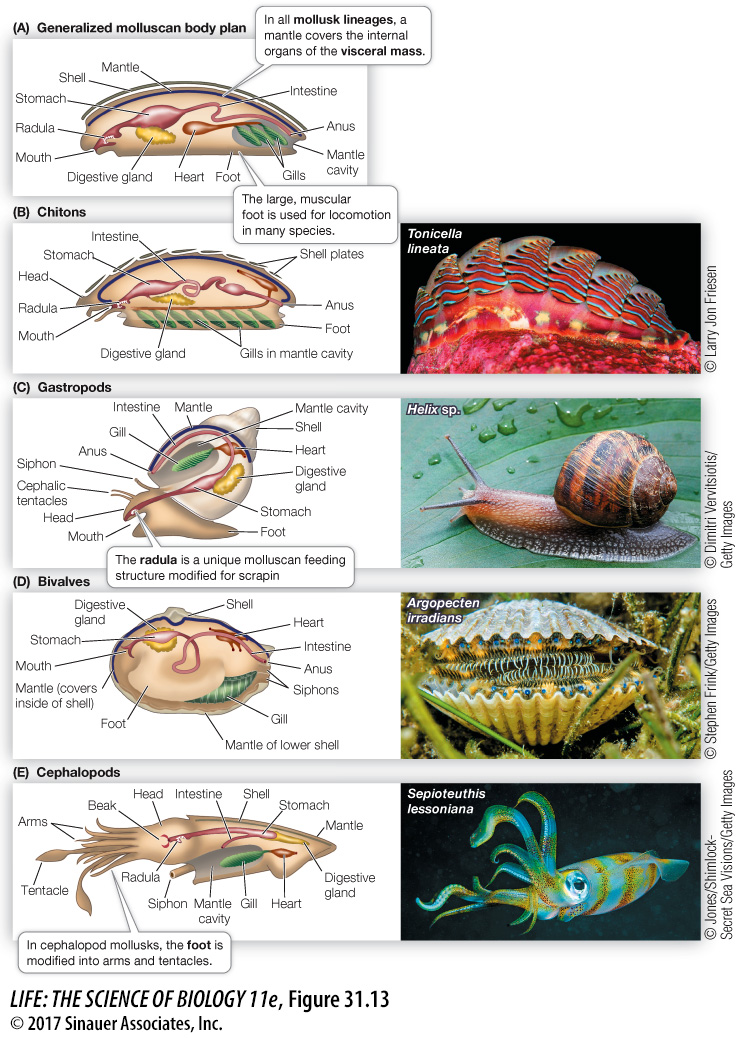

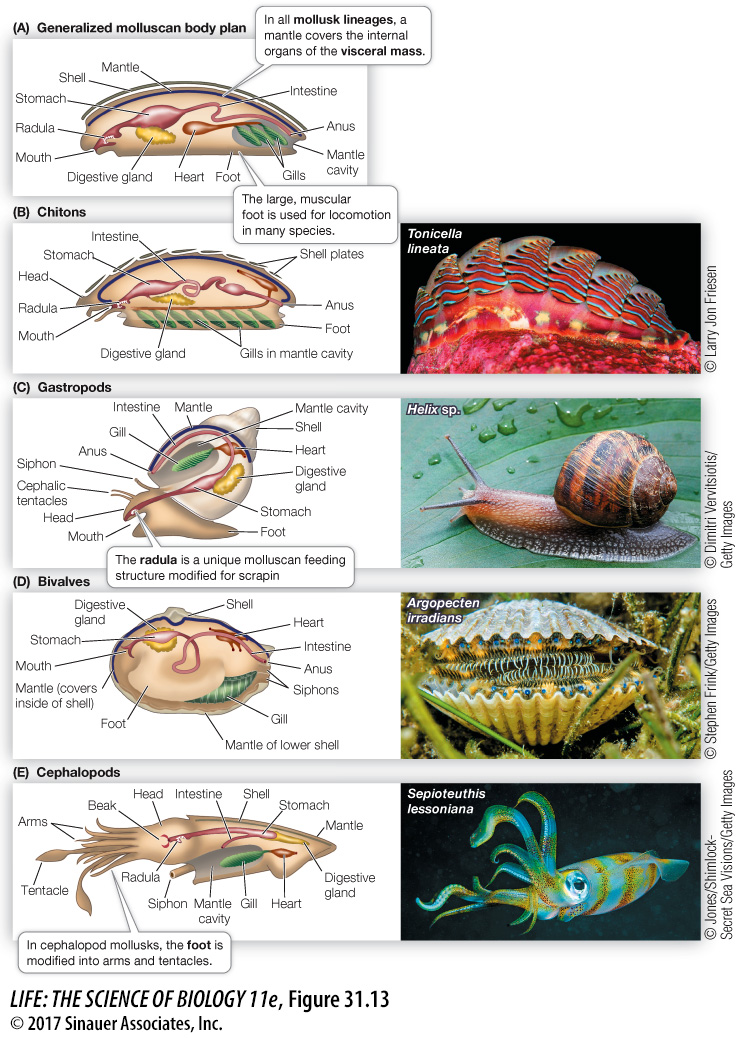

Mollusks are the most diverse group of lophotrochozoans, both in numbers of species and in the environments they occupy. Although the major groups of mollusks differ dramatically in morphology, they all share the same three major body components: a foot, a visceral mass, and a mantle (Figure 31.13A).

Figure 31.13 Organization and Diversity of Molluscan Bodies (A) The major molluscan groups display different variations on a body plan that includes three major components: a foot, a visceral mass of internal organs, and a mantle. In many species, the mantle secretes a calcareous shell. (B) Chitons have eight overlapping calcareous plates surrounded by a girdle. (C) Most gastropods have a single dorsal shell, into which they can retreat for protection. (D) Bivalves get their name from their two hinged shells, which can be tightly closed. (E) Cephalopods are active predators; they use their arms and tentacles to capture prey. This squid has an internal shell but no external shell.

The molluscan foot is a large, muscular structure that originally was both an organ of locomotion and a support for the internal organs. In squids and octopuses, the foot has been modified to form arms and tentacles borne on a head with complex sensory organs. In other groups, such as clams, the foot is a burrowing organ. In some groups the foot is greatly reduced.

The heart and the digestive, excretory, and reproductive organs are concentrated in a centralized, internal visceral mass.

The mantle is a fold of tissue that covers the organs of the visceral mass. The mantle secretes the hard, calcareous shell that is typical of many mollusks.

In most mollusks, the mantle extends beyond the visceral mass to form a mantle cavity. Within this cavity lie gills that are used for gas exchange. When cilia on the gills beat, they create a current of water. The tissue of the gills, which is highly vascularized (contains many blood vessels), takes up oxygen from the water and releases carbon dioxide. Many mollusk species use their gills as filter-feeding devices, whereas others feed using a rasping structure known as a radula to scrape algae from rocks. In some mollusks, such as the marine cone snails, the radula has been modified into a drill or poison dart.

In all mollusks except cephalopods, the blood vessels do not form a closed system. Blood and other fluids empty into a large, fluid-filled hemocoel, through which fluids move and deliver oxygen to the internal organs. Eventually the fluids reenter the blood vessels and are moved by a heart.

Page 669

Page 670

Monoplacophorans were the most abundant mollusks during the Cambrian period, 500 million years ago, but only a few species survive today. In monoplacophorans, in contrast to all other living mollusks, the gas exchange organs, muscles, and excretory pores are repeated over the length of the body.

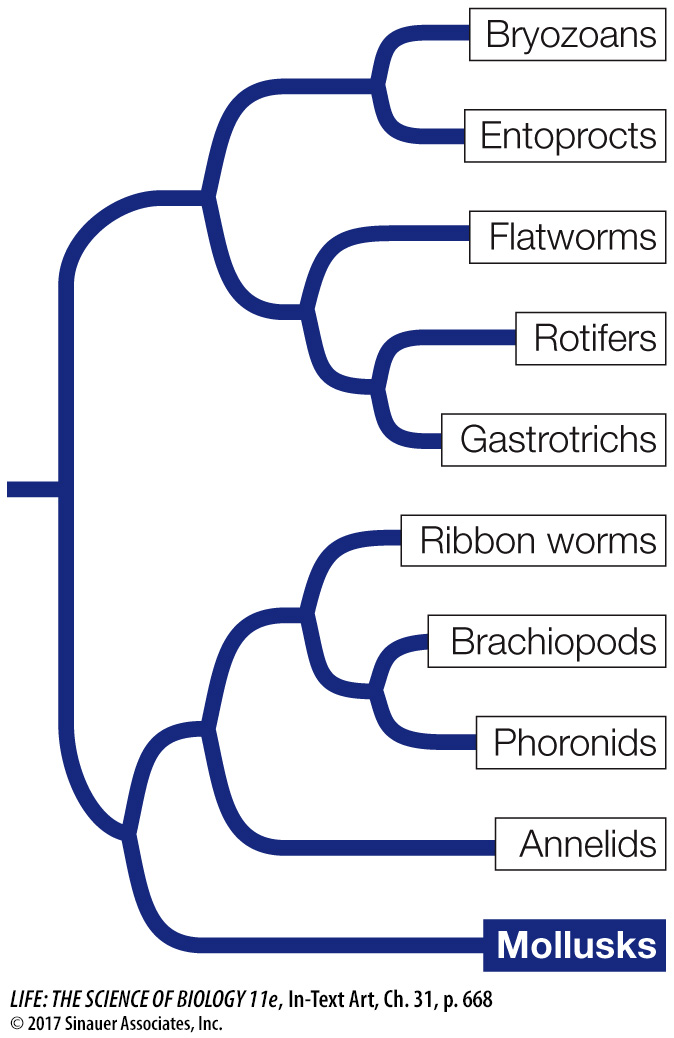

The four major clades of living mollusks are the chitons, gastropods, bivalves, and cephalopods. Each of these groups is readily identifiable and distinct, even though they share variations on a common body plan.

CHITONS Eight overlapping calcareous plates, surrounded by a structure known as the girdle, protect the internal organs and muscular foot of chitons (Figure 31.13B). The chiton body is bilaterally symmetrical, and the internal organs, particularly the digestive and nervous systems, are relatively simple. Most chitons are marine omnivores that scrape algae, bryozoans, and other organisms from rocks with a sharp radula. An adult chiton spends most of its life clinging tightly to rock surfaces with its large, muscular, mucus-covered foot. It moves slowly by means of rippling waves of muscular contraction in the foot. Fertilization in most chitons takes place in the water, but in a few species fertilization is internal and embryos are brooded within the body. There are approximately 1,000 living species of chitons known.

GASTROPODS Gastropods (Figure 31.13C) are the most species-rich and widely distributed mollusks, with about 85,000 known living species. Snails, whelks, limpets, slugs, nudibranchs (sea slugs), and abalones are all gastropods. Most species move by gliding on the muscular foot, but in a few species—the sea butterflies and heteropods—the foot is a swimming organ with which the animal moves through open ocean waters.

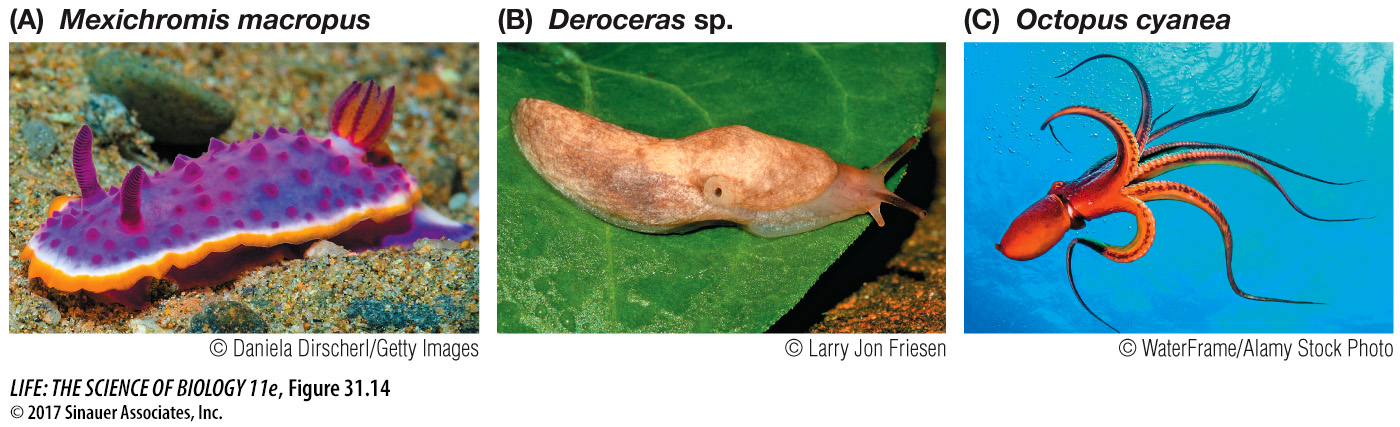

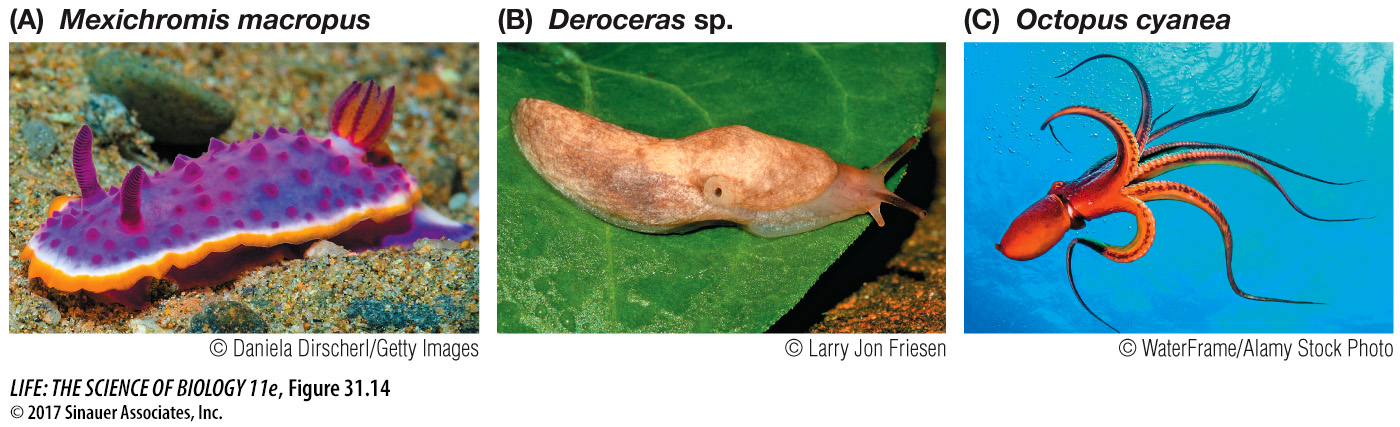

Marine nudibranchs and terrestrial slugs are gastropods that have lost their protective shell over the course of evolution (Figure 31.14). Without a shell, these groups rely on other forms of protection from predation. The coloration of many nudibranchs is aposematic, meaning that it serves to warn potential predators of toxicity. Other nudibranch species and most terrestrial slugs exhibit camouflaged coloration.

Figure 31.14 Mollusks in Some Groups Have Lost Their Shells (A) Nudibranchs (“naked gills”), also called sea slugs, are shell-less gastropods. This species is brightly colored, alerting potential predators of its toxicity. (B) Slugs are terrestrial, shell-less gastropods that feed on decomposing vegetation on the damp forest floor. (C) Octopuses have neither an external nor an internal shell, which allows these cephalopods to squeeze through tight spaces.

Media Clip 31.6 Octopuses Can Pass through Small Openings

Shelled gastropods have one-piece shells. The only mollusks that live in terrestrial environments—land snails and slugs—are gastropods. In these terrestrial species, the mantle tissue is modified into a highly vascularized lung.

BIVALVES Clams, oysters, scallops, and mussels are all familiar bivalves. The approximately 30,000 known species are found in both marine and freshwater environments. Bivalves have a hinged, two-part shell that extends over the sides of the body as well as the top (Figure 31.13D). Many clams use the foot to burrow into mud and sand. Bivalves feed by taking in water through an opening called an incurrent siphon and filtering food from the water with their large gills, which are also the main sites of gas exchange. Water and gametes exit through the excurrent siphon. Fertilization takes place in open water in most species.

CEPHALOPODS The cephalopods—squids, cuttlefish, octopuses, and nautiluses—first appeared near the beginning of the Cambrian period. By the Ordovician period a variety of types were present. Today there are about 800 described living species. In these mollusks the excurrent siphon is modified to allow the animal to control the volume of the mantle cavity and thereby bring in or expel water (Figure 31.13E). The modification of the mantle into a device for forcibly ejecting water from the cavity through the siphon enables these animals to move rapidly through the water by “jet propulsion.” With their greatly enhanced mobility, cephalopods became the major predators in the open waters of the Devonian oceans. They remain important marine predators today.

As is typical of active, rapidly moving predators, cephalopods have a head with complex sensory organs—most notably eyes that are comparable to those of vertebrates in their ability to resolve images. The head is closely associated with a large, branched foot that bears the arms and/or tentacles and a siphon. Arms are distinguished by the presence of suckers along most of their length. Tentacles, in contrast, have suckers only near the tips or lack suckers altogether. Octopuses typically have eight arms and no tentacles, whereas squids and cuttlefishes have eight arms plus two tentacles. Cephalopods use their arms and tentacles to capture and subdue prey; octopuses also use their arms to move over the substrate. The large, muscular mantle provides a solid external supporting structure. The gills hang in the mantle cavity.

Page 671

Many early cephalopods had an external chambered shell divided by partitions. The only surviving cephalopods with such shells are the nautiluses (genus Nautilus). The chambers inside nautilus shells are connected by a strand of tissue that runs through ducts in the partitions. Blood in this tissue carries water from the chambers and gases into the chambers, thus providing buoyancy. Most cephalopods retain an internal shell that functions for internal support and, in some species, is also chambered and buoyant. Octopuses have completely lost their shells, which allows them to compress their bodies through very small openings.