Chelicerates have pointed, nonchewing mouthparts

In the chelicerates, the head bears two pairs of pointed appendages modified to form mouthparts, called chelicerae, that are used to grasp (rather than chew) prey. Chelicerates typically have a two-part body plan, with anterior segments fused to form a cephalothorax, and rear segments fused to form an abdomen. In some groups, such as mites and ticks, there is no clear distinction between these two body parts. Most chelicerates have four pairs of walking legs. The 114,000 described species are grouped into three major clades: pycnogonids, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids.

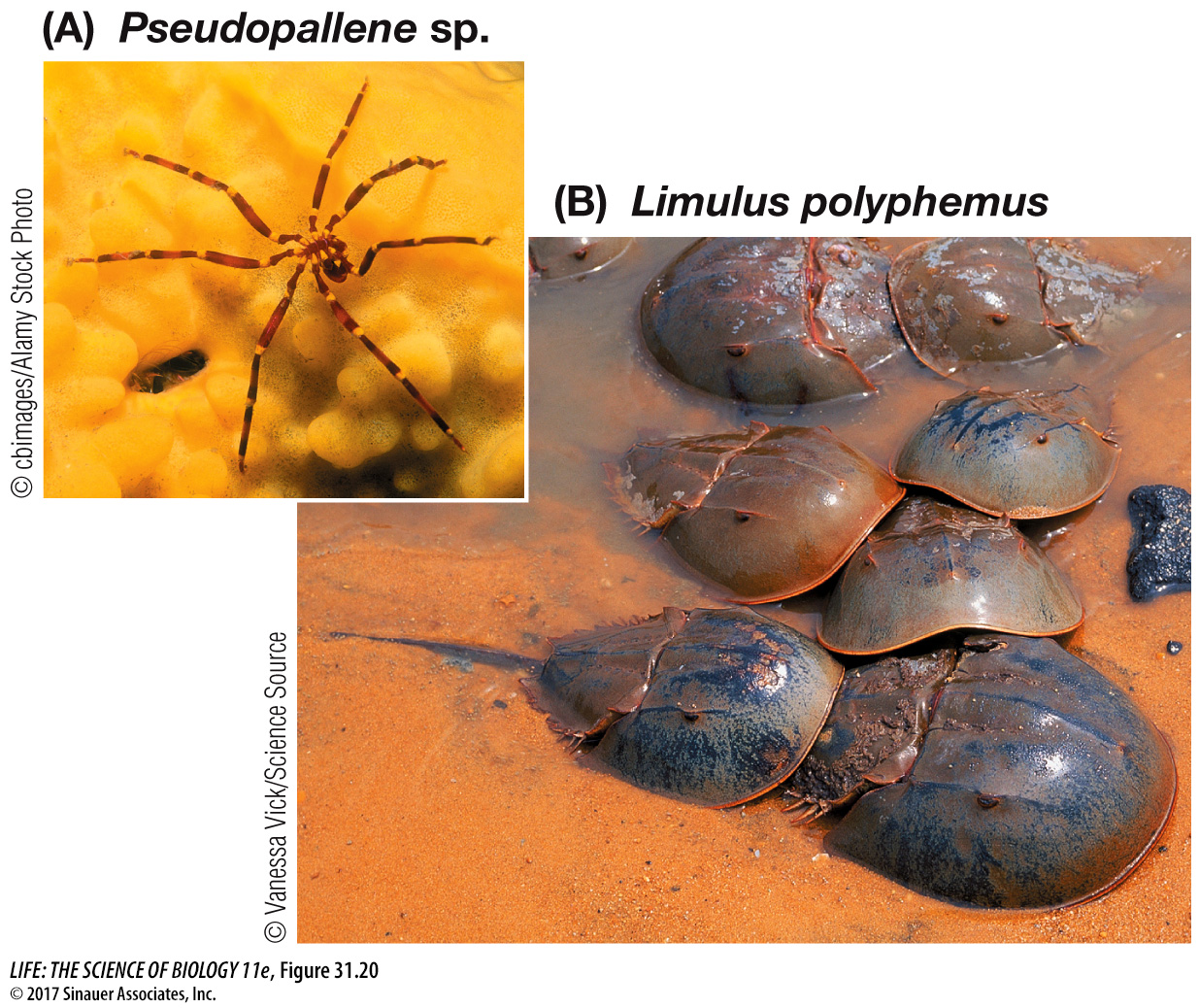

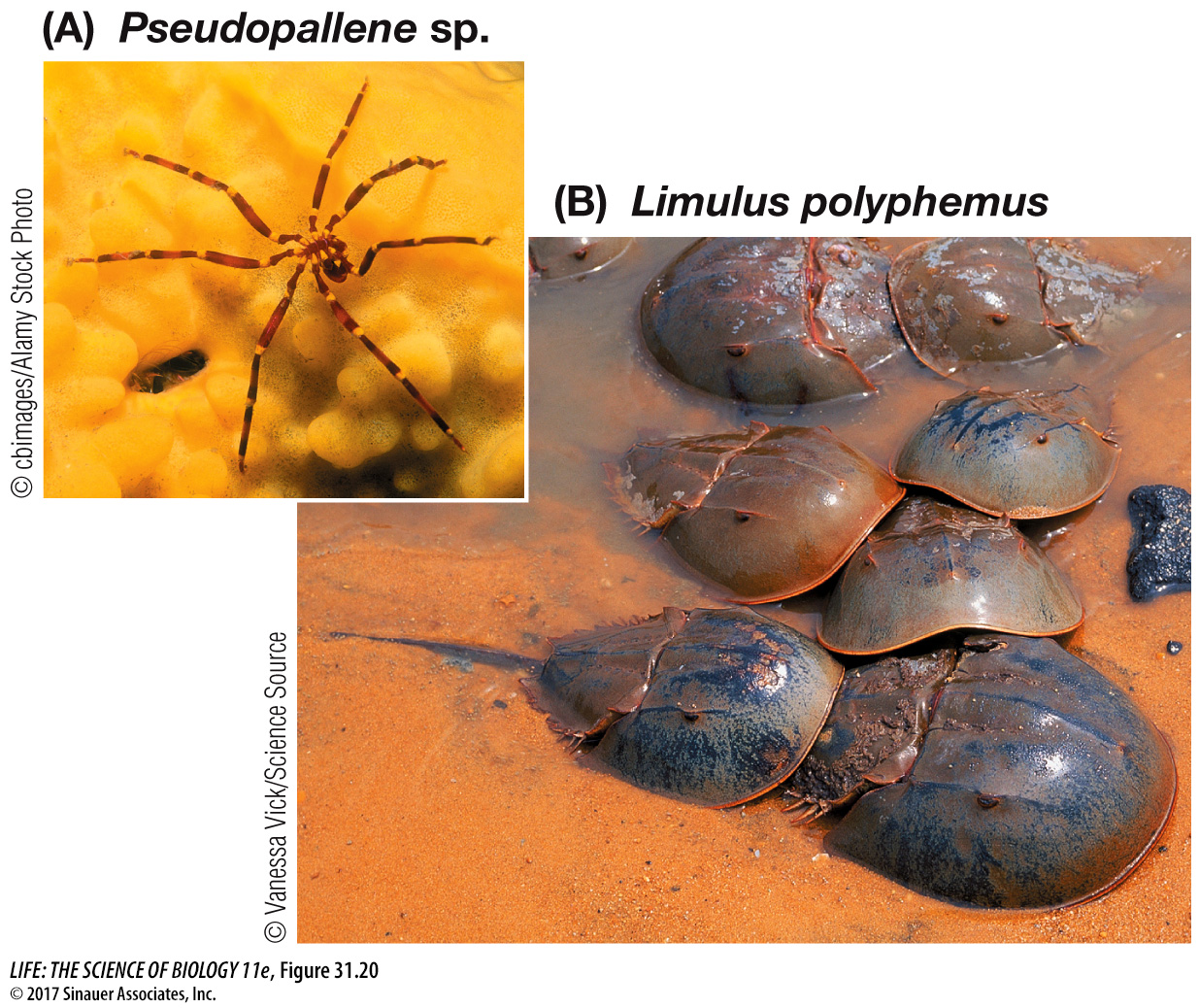

The pycnogonids, or sea spiders, make up a poorly known group of about 1,000 marine species (Figure 31.20A). Most are small, with leg spans less than 1 centimeter, but some deep-sea species have leg spans up to 60 centimeters. A few pycnogonids eat algae, but most are carnivorous, eating a variety of small invertebrates.

Figure 31.20 Two Small Chelicerate Groups (A) Although they are not spiders, it is easy to see how sea spiders got their common name. (B) A spawning aggregation of horseshoe crabs. Horseshoe crabs, like the onychophorans (see Figure 31.18B), are an example of “living fossils.”

There are only four living species of horseshoe crabs, but many close relatives are known from fossils. Horseshoe crabs, which have changed very little morphologically over their long history, have a large horseshoe-shaped covering over most of the body. They are common in shallow waters along the eastern coast of North America and the southern and eastern coasts of Asia, where they scavenge and prey on bottom-dwelling animals. Periodically they crawl into the intertidal zone in large numbers to mate and lay eggs (Figure 31.20B).

Arachnids are abundant in terrestrial environments. Most arachnids have a simple life cycle in which miniature adults hatch from internally fertilized eggs and begin independent lives almost immediately. Some arachnids retain their eggs during development and give birth to live young.

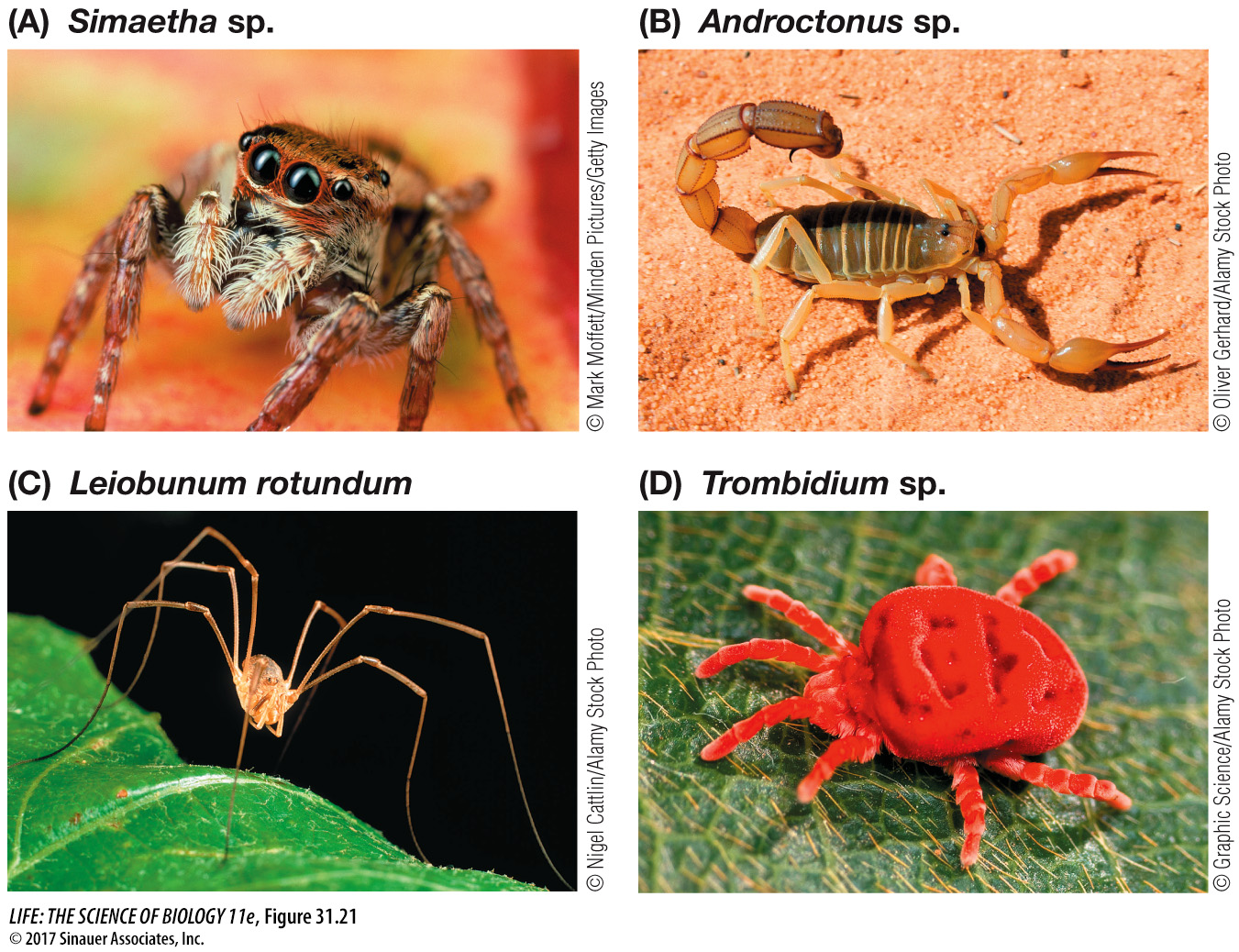

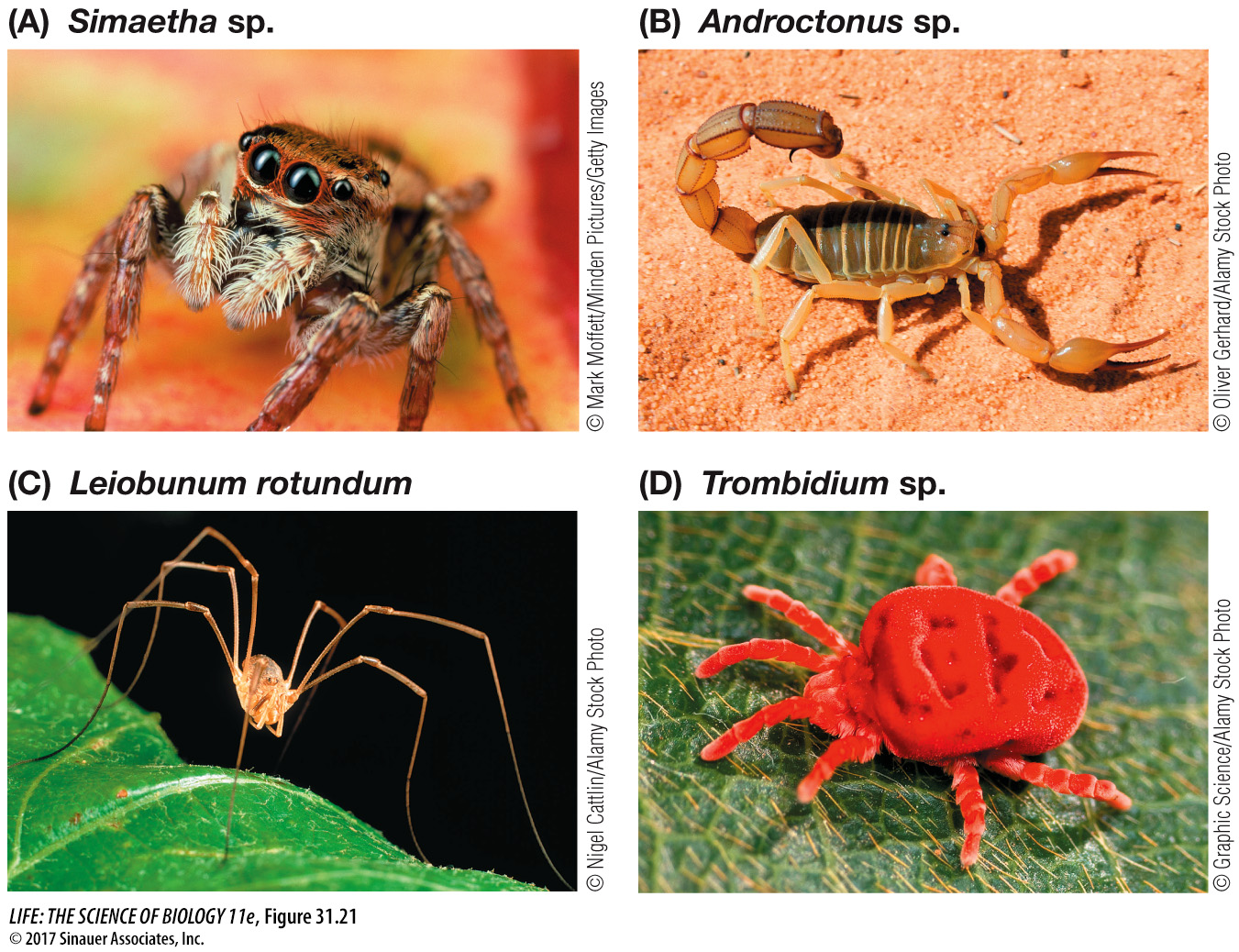

The most species-rich and abundant arachnids are the spiders, scorpions, harvestmen, mites, and ticks (Figure 31.21). More than 60,000 described species of mites and ticks live in soil, leaf litter, mosses, and lichens, under bark, and as parasites of plants and animals. Mites are vectors for wheat and rye mosaic viruses; they cause mange in domestic animals and skin irritation in humans.

Figure 31.21 Arachnid Diversity (A) Jumping spiders are active, visually oriented, diurnal predators of insects. (B) Scorpions are nocturnal predators of small animals. (C) Harvestmen, also called daddy longlegs, are scavengers. (D) Mites include many free-living species as well as blood-sucking ectoparasites.

Page 676

Spiders, of which about 50,000 species have been described, are important terrestrial predators with hollow chelicerae, which they use to inject venom into their prey. Some have excellent vision that enables them to chase and seize their prey. Others spin elaborate webs made of protein threads in which they snare prey. The threads are produced by modified abdominal appendages connected to internal glands that secrete the proteins, which solidify on contact with air. The webs of different groups of spiders are strikingly varied, and this variation enables the spiders to position their snares in many different environments for many different types of prey.