Adults of most lancelets and tunicates are sedentary

The 35 species of lancelets are small animals that rarely exceed 5 centimeters in length. The notochord, which provides body support, extends the entire length of the body throughout the animal’s life (see Figure 32.7B). Lancelets are found in shallow marine and brackish waters worldwide. Most of the time they lie covered in sand with their head protruding above the sediment, but they can swim. The pharynx has been enlarged and modified to form a structure called a pharyngeal basket, with which the lancelet filters prey from the water. During the reproductive season, the gonads of males and females enlarge greatly. At spawning, the walls of the gonads rupture, releasing eggs and sperm into the water column, where fertilization takes place.

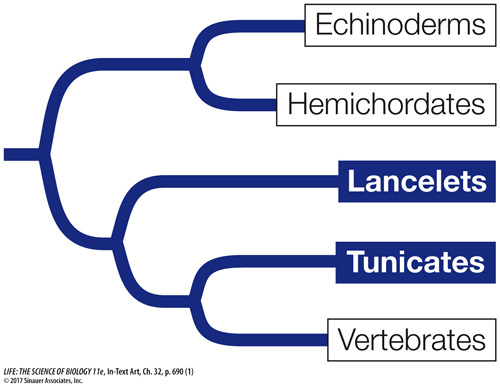

All members of the three major tunicate groups—

In addition to its pharyngeal slits, a sea squirt larva has a dorsal hollow nerve cord and a notochord that is restricted mostly to the tail region (see Figure 32.7A). Bands of muscle surround the notochord, which provide support for the body. After a short time swimming in the plankton, the larvae of most species settle on the seafloor and transform into sessile adults. The swimming, tadpolelike larvae suggest a close evolutionary relationship between tunicates and vertebrates (see Figure 21.6).

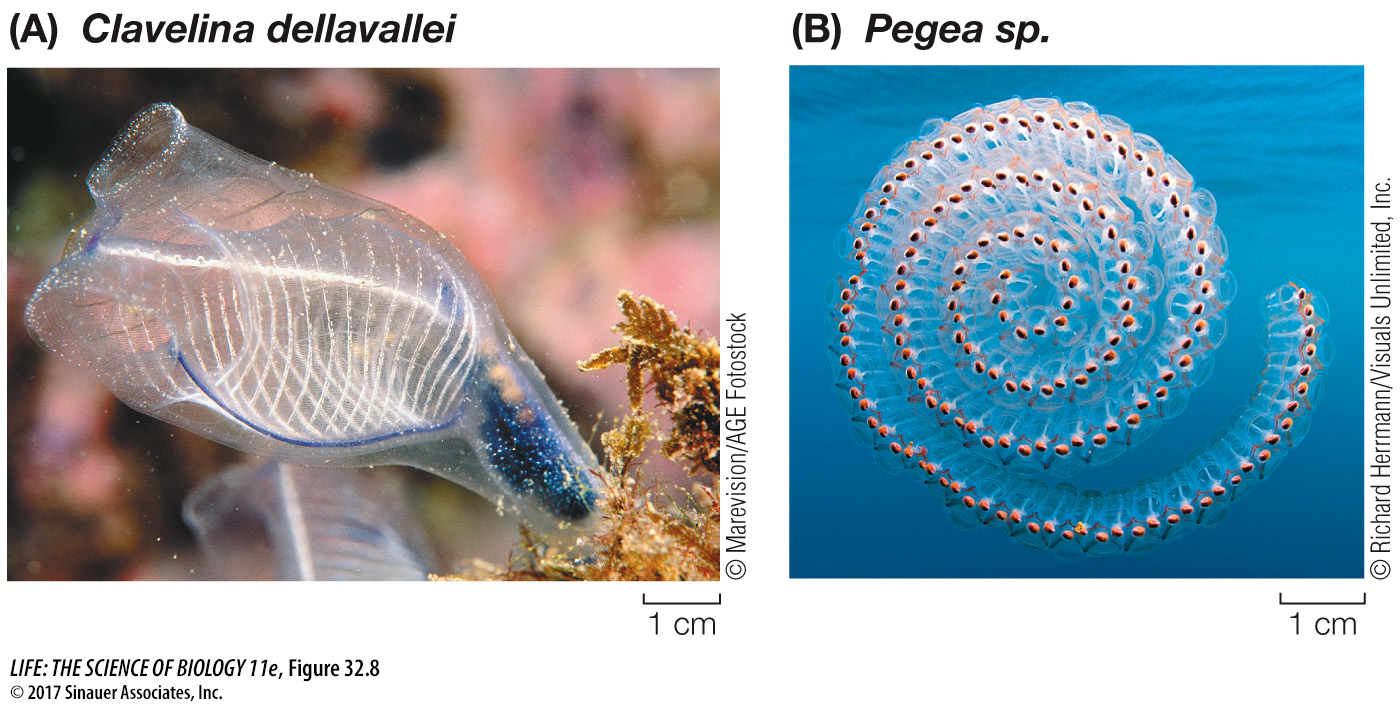

Thaliaceans (salps and their relatives) are tunicates that can live singly or in chainlike colonies up to several meters long (Figure 32.8B). They float in tropical and subtropical oceans at depths down to 1,500 meters. Larvaceans are solitary planktonic animals that retain the notochord and dorsal hollow nerve cord throughout their lives. Most larvaceans are less than 5 millimeters long, but some species that live near the bottom of deep ocean waters build delicate casings of mucus that may be more than a meter wide. They snare sinking organic particles (their primary food source) with elaborate filters built into their mucus “houses.” When the old “house” gets clogged with excess debris, the animal builds a new one.