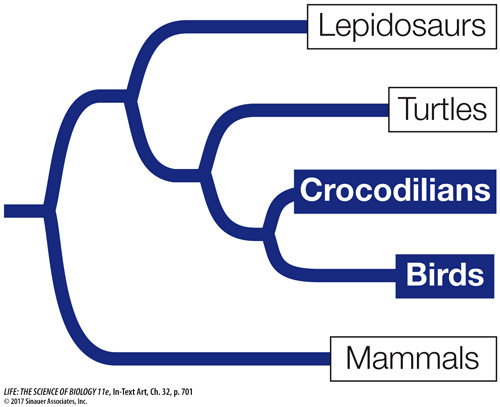

Crocodilians and birds share their ancestry with the dinosaurs

Another reptilian clade, the archosaurs, includes the crocodilians, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and birds. Only the crocodilians and birds are represented by living species today. Modern crocodilians—crocodiles, caimans, gharials, and alligators—are confined to tropical and warm temperate environments (Figure 32.22A). All crocodilians are carnivorous; they eat vertebrates of all kinds, including large mammals. Crocodilians spend much of their time in water, but they lay their eggs in nests they build on land or on floating piles of vegetation. The eggs are warmed by heat generated by decaying organic matter that the female places in the nest. The female provides other forms of parental care as well: typically she guards the eggs until they hatch, and in some species she continues to guard and communicate with her offspring after they hatch.

Figure 32.22 Archosaurs The two surviving groups of archosaurs are very different. (A) The crocodilians live in tropical and warm temperate climates. This saltwater crocodile lives in saltwater and estuarine environments along Australia’s coast. (B) Birds are the only other living archosaur group, represented here by the winged but flightless southern cassowary.

Dinosaurs rose to prominence about 215 million years ago and dominated terrestrial environments for about 150 million years. However, only one group of dinosaurs, the birds, survived the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. During the Mesozoic, most terrestrial animals more than a meter long were dinosaurs. Many were agile and could run rapidly; they had special muscles that enabled the lungs to be filled and emptied while the limbs moved. We can infer the existence of such muscles in dinosaurs from the structure of the vertebral column in fossils. Some of the largest dinosaurs weighed as much as 70,000 kilograms.

Biologists have long accepted the phylogenetic position of birds among the reptiles, although birds clearly have many unique, derived morphological features. In addition to the strong morphological evidence for this placement, fossil and molecular data emerging over the last few decades have provided definitive supporting evidence. Birds are a specialized group of theropods, a clade of predatory dinosaurs that shared such traits as a bipedal stance, hollow bones, a furcula (“wishbone”), elongated metatarsals with three-fingered feet, elongated forelimbs with three fingers, and a pelvis that points backward. Modern birds are endothermic, meaning that they regulate their body temperatures by producing and retaining metabolic heat, rather than by absorbing heat from their external environment (see Key Concept 39.4). Although we cannot directly assess this physiological trait in extinct species, many fossil theropods share morphological traits that suggest they may have been endothermic as well.

The living bird species fall into two major groups that diverged about 80–90 million years ago from a flying ancestor. The few modern descendants of one lineage include a group of secondarily flightless and weakly flying birds, some of which are very large. This group, called the palaeognaths, includes the South and Central American tinamous and several large flightless birds of the southern continents—the rheas, emu, kiwis, cassowaries, and the world’s largest birds, the ostriches (Figure 32.22B). The second lineage, the neognaths, has left a much larger number of descendants, most of which have retained the ability to fly.