Feathers allowed birds to fly

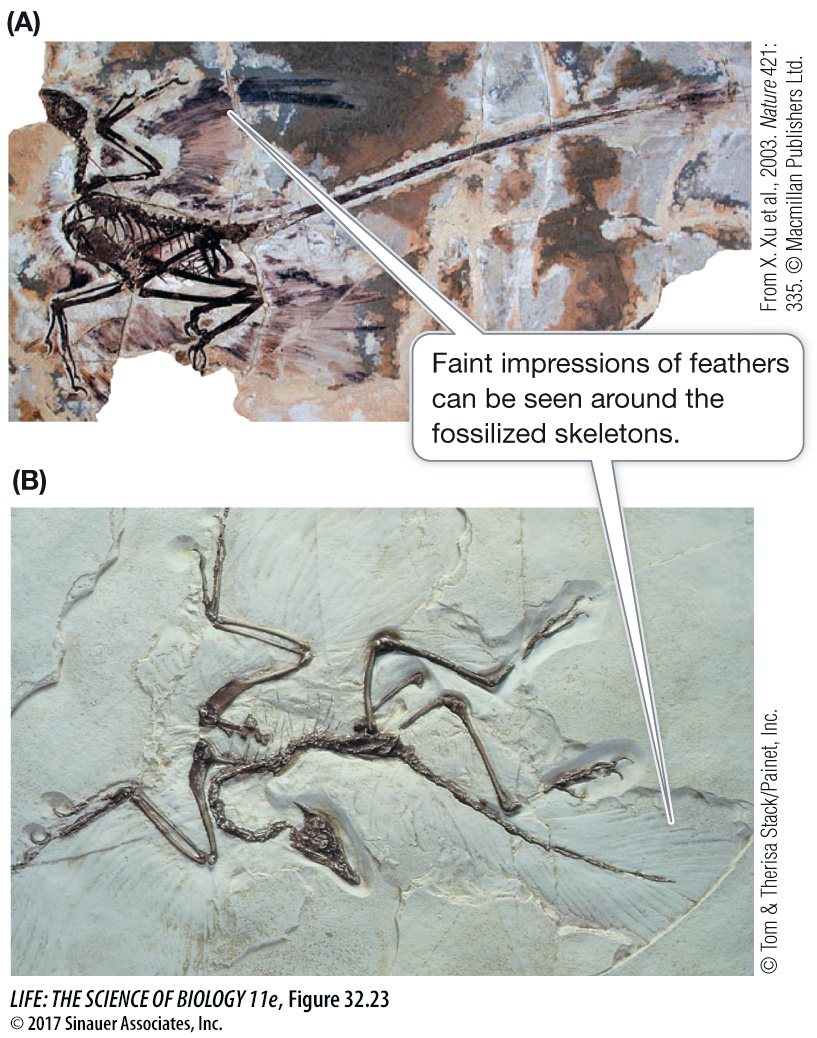

Fossil theropods discovered in early Cretaceous deposits in Liaoning Province, in northeastern China, show that the scales of some small predatory dinosaurs were highly modified to form feathers. Initially these feathers were simply a body covering that probably provided insulation and enhanced coloration. But the feathers of some later dinosaurs, such as Microraptor gui, were structurally similar to those of modern birds (Figure 32.23A).

Figure 32.23 Mesozoic Bird Relatives Fossils support the evolution of birds from other theropods. (A) Microraptor gui was a feathered theropod from the early Cretaceous (about 140 mya). (B) Archaeopteryx was even more closely related to modern birds.

Another theropod that was even more closely related to modern birds, Archaeopteryx, lived about 150 million years ago. Archaeopteryx had teeth (unlike modern birds), but it was covered with feathers that are virtually identical to those of birds (Figure 32.23B). It also had well-developed wings, a long tail, and a furcula to which some of the flight muscles were probably attached. Archaeopteryx had clawed fingers on its forelimbs, but it also had typical perching bird claws on its hindlimbs. It probably lived in trees and shrubs and used the fingers to assist it in clambering over branches. It probably glided or flew weakly. The descendants of Archaeopteryx and similar Mesozoic theropods were the modern birds, most of which are accomplished fliers.

Media Clip 32.6 Falcons in Flight

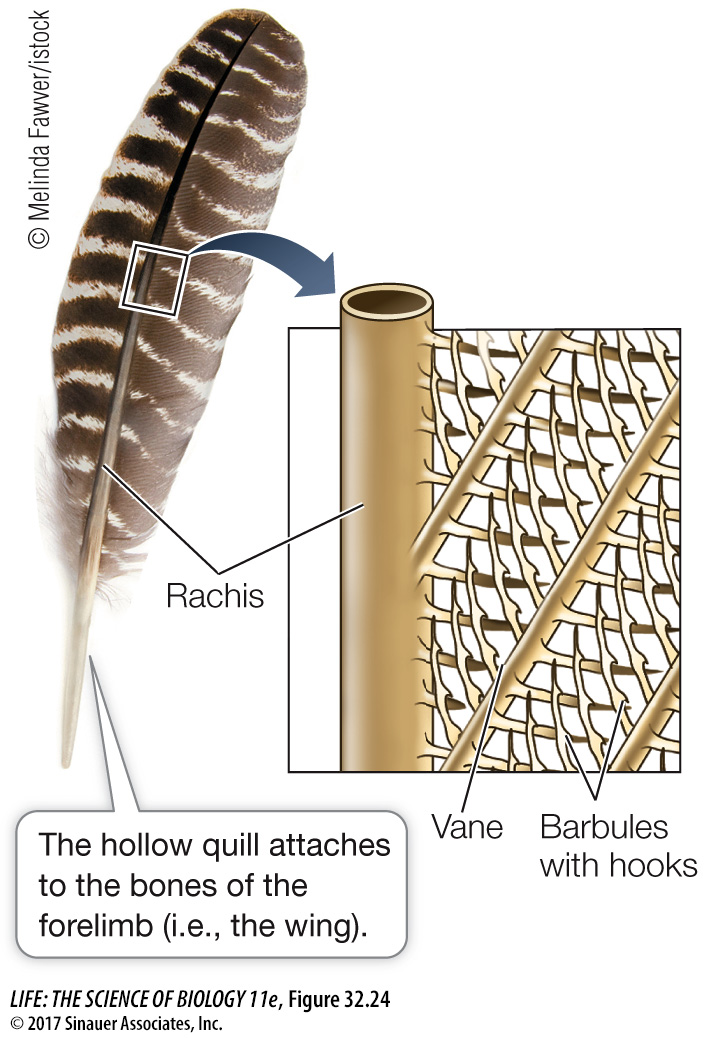

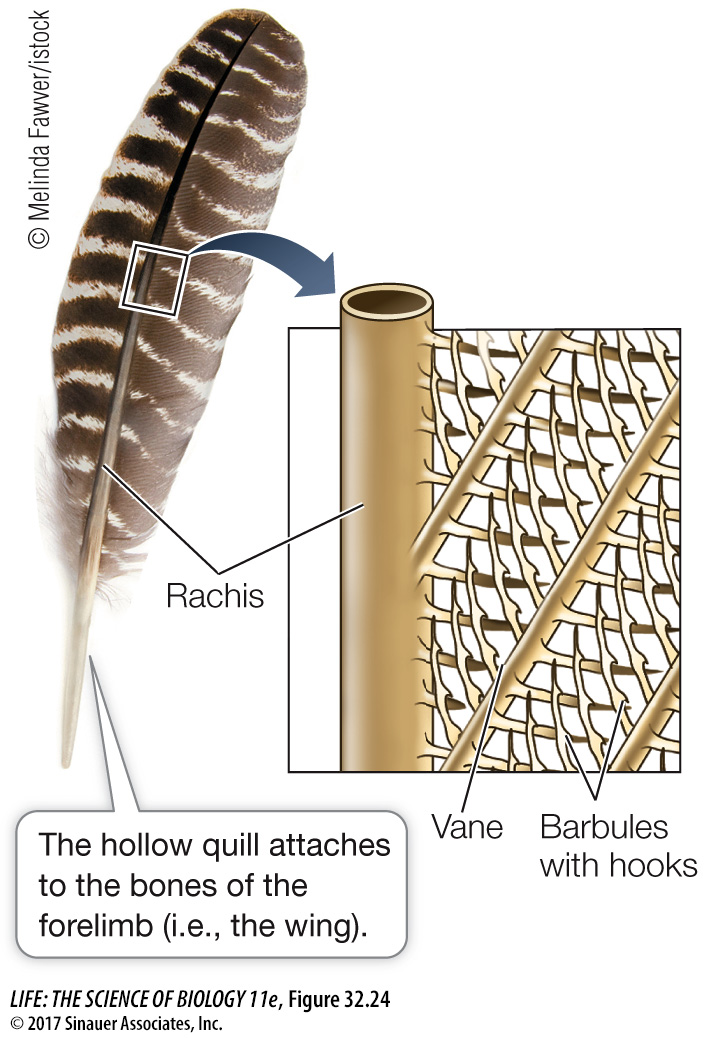

The evolution and specialization of feathers was a major force for diversification. Feathers are lightweight, but they are strong and structurally complex (Figure 32.24). The stiff central shaft of the flight feathers on a bird’s wings arises from the skin of the forelimbs to create the flying surfaces. Other strong feathers sprout like a fan from the shortened tail and serve as stabilizers during flight. The feathers that cover the body, along with an underlying layer of down feathers, provide birds with insulation that helps them survive in virtually all of Earth’s climates.

Figure 32.24 Feather Anatomy The flight feathers of birds are attached to the wing’s skin by the hollow portion, or quill, of a stiff central shaft. The rachis is the solid portion of the shaft from which radiate fine branches (vanes) with interlocking hooks and barbules. Overall, this structure represents a major evolutionary innovation: a strong, lightweight surface that enables flight.

Page 703

The bones of theropod dinosaurs, including birds, are hollow with internal struts that increase their strength. Hollow bones would have made early theropods lighter and more mobile; later they facilitated the evolution of flight. The sternum (breastbone) of flying birds forms a large, vertical keel to which the flight muscles are attached.

Flight is metabolically expensive. A flying bird consumes energy at a rate about 15–20 times faster than a running lizard of the same weight. Because birds have such high metabolic rates, they generate large amounts of heat. They control the rate of heat loss using their feathers, which may be held close to the body or elevated to alter the amount of insulation they provide. The lungs of birds allow air to flow through unidirectionally rather than pumping air in and out (see Key Concept 48.2). This flow-through structure of the lungs increases the efficiency of gas exchange and thereby supports a high metabolic rate.

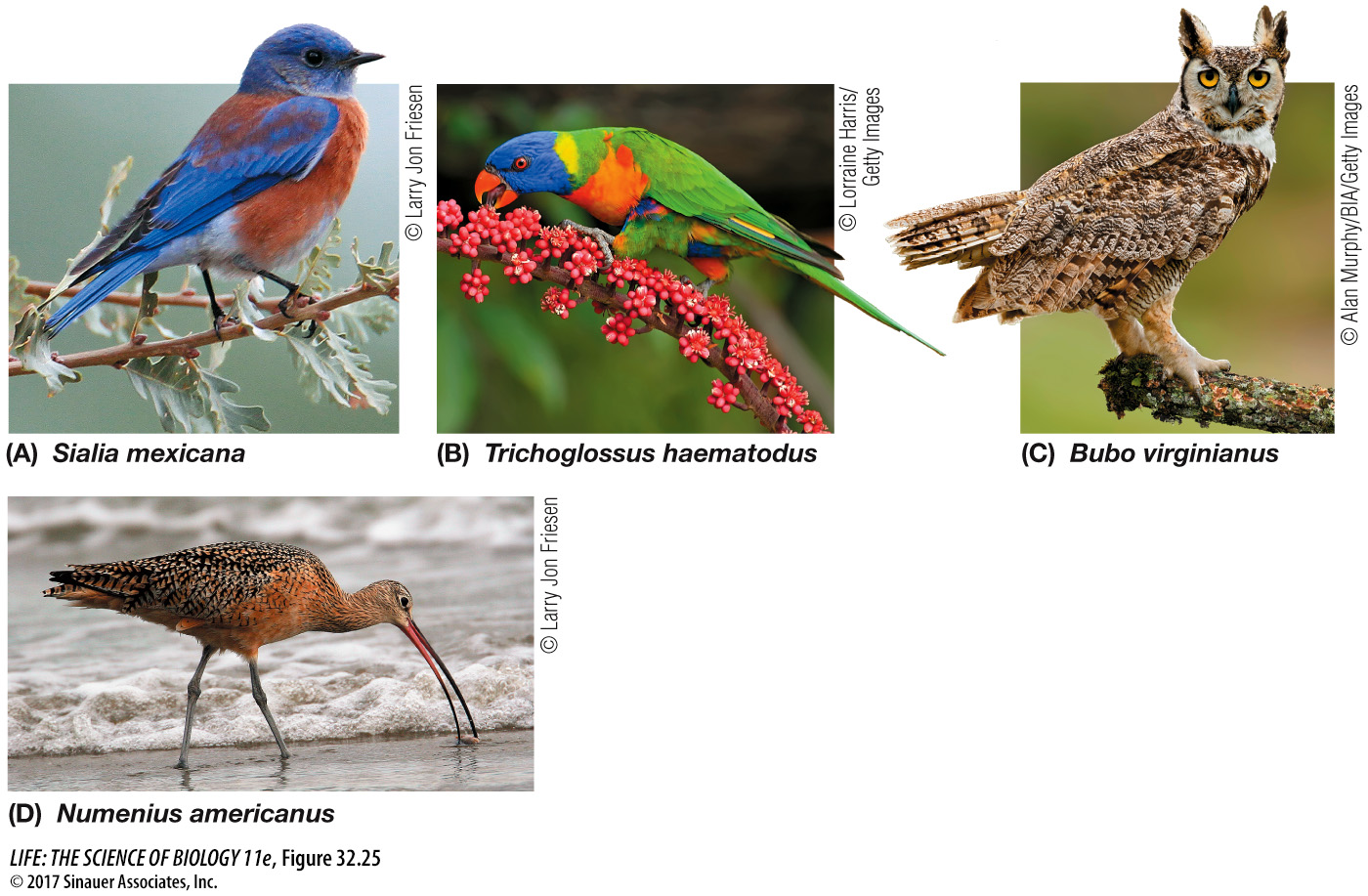

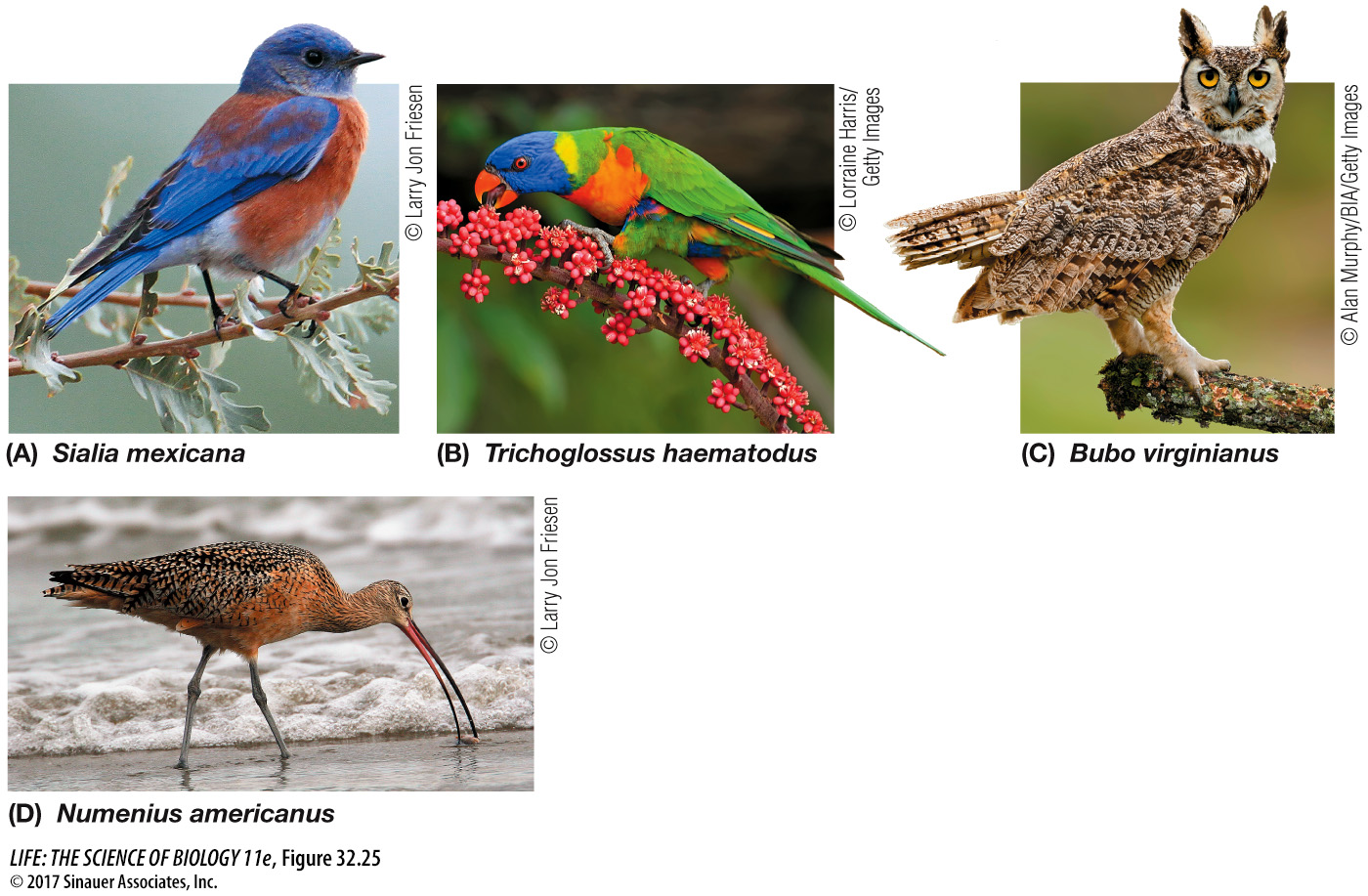

There are about 10,000 species of living birds, which range in size from the 150-kilogram ostriches to a tiny hummingbird weighing only 2 grams (Figure 32.25). The teeth so prominent among other dinosaurs were secondarily lost in the ancestral birds, but birds nonetheless eat almost all types of animal and plant material. Insects and fruits are the most important dietary items for terrestrial species. Birds also eat seeds, nectar and pollen, leaves and buds, carrion, and other vertebrates. By eating the fruits and seeds of plants, birds serve as major agents of seed dispersal.

Figure 32.25 Diversity among the Birds (A) Perching, or passeriform, birds such as this western bluebird constitute the most species-rich of all bird groups. (B) Some 375 species of parrots, macaws, parakeets, and lorikeets such as the one shown here are another large bird group. (C) The great horned owl is a nighttime predator that can find prey using its sensitive auditory “sonar” system. (D) The long-billed curlew of North America is one of many species of wading birds.