Bipedal locomotion evolved in human ancestors

About 6 million years ago in Africa, a lineage split occurred that would lead to the chimpanzees on the one hand and to the hominin clade, which includes modern humans and their extinct close relatives, on the other.

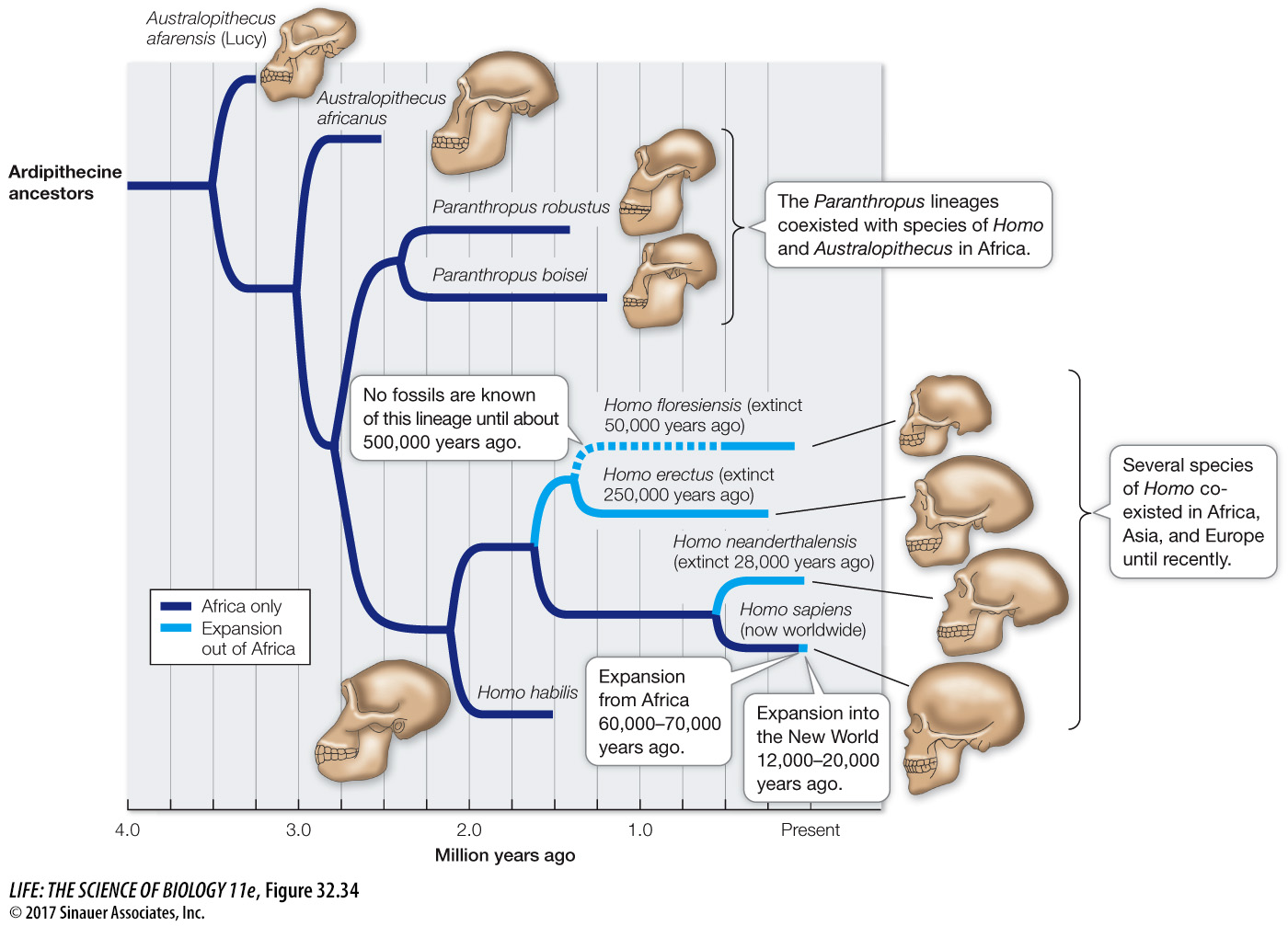

The earliest protohominins, known as ardipithecines, had distinct morphological adaptations for bipedal locomotion (walking on two legs). Bipedal locomotion frees the forelimbs to manipulate objects and to carry them while walking. It also elevates the eyes, enabling the animal to see over tall vegetation to spot predators and prey. Bipedal locomotion is also energetically more economical than quadrupedal locomotion (walking on four legs). All three advantages were probably important for the ardipithecines and their descendants, the australopithecines (Figure 32.34).

The first australopithecine skull was found in South Africa in 1924. Since then australopithecine fossils have been found at many sites in Africa. The most complete fossil skeleton yet found was discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. The skeleton, approximately 3.5 million years old, was that of a young female who has since become known to the world as “Lucy.” Lucy was assigned to the species Australopithecus afarensis. Fossil remains of more than 100 A. afarensis individuals have since been discovered, and there have been recent discoveries of fossils of other australopithecine species that lived in Africa 4–

Experts disagree over how many species are represented by australopithecine fossils, but it is clear that multiple species of hominins lived together over much of eastern Africa several million years ago. A lineage of larger species (weighing about 40 kilograms) is represented by Paranthropus robustus and P. boisei, both of which died out between 1 and 1.5 million years ago. A lineage of smaller australopithecines gave rise to the genus Homo.

Early members of the genus Homo lived contemporaneously with Paranthropus in Africa for about a million years. Some 2-

Another extinct hominin species, Homo erectus, arose in Africa about 1.6 million years ago. Soon thereafter it had spread as far as eastern Asia, becoming the first hominin to leave Africa. Members of H. erectus were nearly as large as modern people, but their brains were smaller and they had comparatively thick skulls. The cranium, which had thick, bony walls, may have been an adaptation to protect the brain, ears, and eyes from impacts caused by a fall or a blow from a blunt object. What would have been the source of such blows? Fighting with other H. erectus individuals is a possible answer.

Homo erectus used fire for cooking and for hunting large animals, and made characteristic stone tools that have been found in many parts of Africa and Asia. Populations of H. erectus survived until at least 250,000 years ago, although more recent fossils may also be attributable to this species. In 2004 some 18,000-