Human brains became larger as jaws became smaller

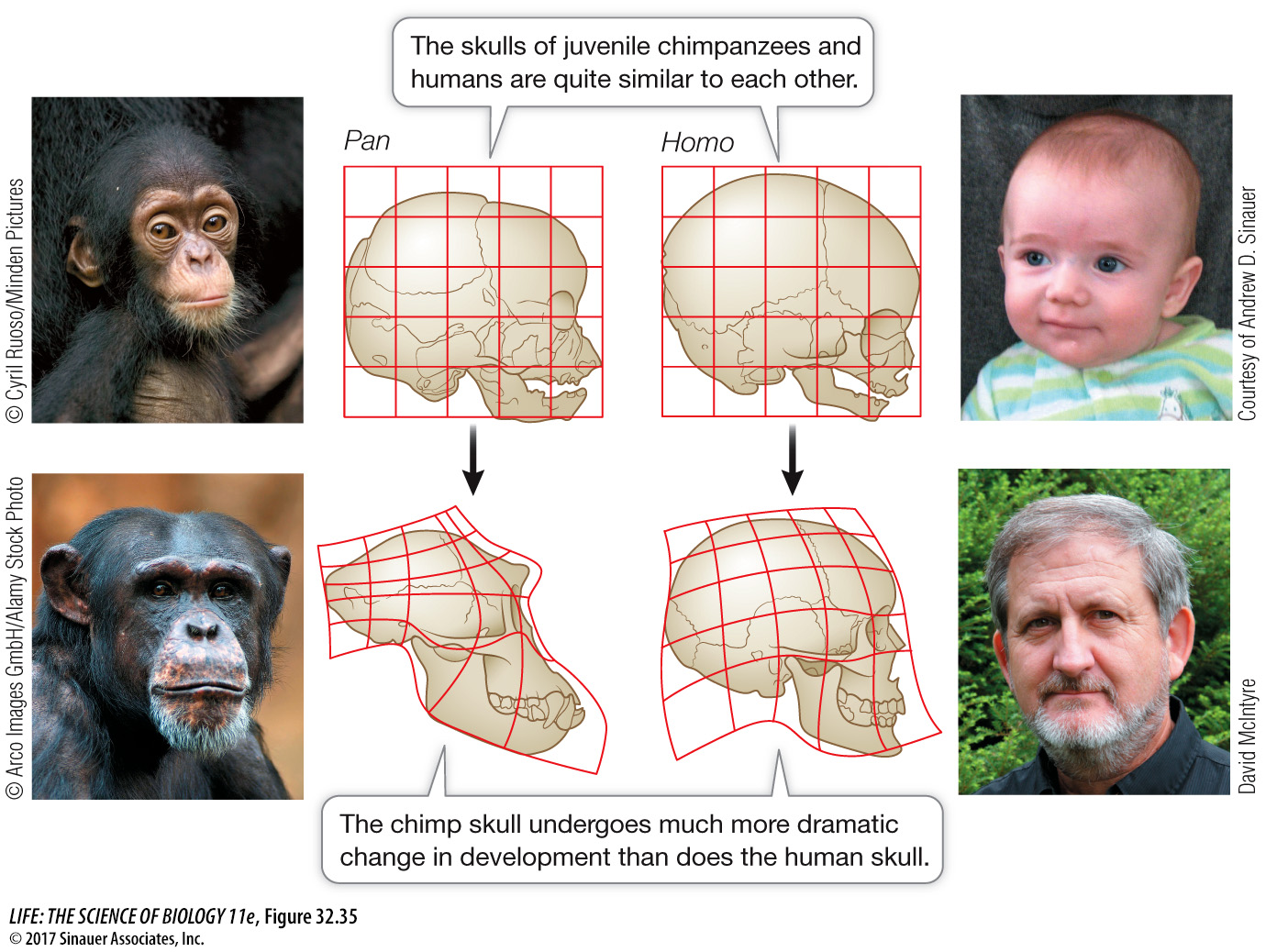

In another hominin lineage that diverged from H. erectus and H. floresiensis, the brain increased rapidly in size, and the jaw muscles, which were large and powerful in earlier hominins, dramatically decreased in size. These two changes were simultaneous, which suggests that they might have been developmentally linked. These changes are another example of evolution by neoteny (which, you may recall from our discussion of amphibians, is the retention of juvenile traits through delayed somatic development). Human and chimpanzee skulls are similar in shape at birth, but chimpanzee skulls undergo a dramatic change in shape as the animals mature (Figure 32.35). In particular, the jaw grows considerably in relation to the brain case. As human skulls grow, relative proportions much closer to those of the juvenile skull are retained, which results in a large brain case and small jaw compared with those of chimpanzees. A mutation in a regulatory gene that is expressed only in the head may have removed a barrier that had previously prevented this remodeling of the human cranium.

The striking enlargement of the brain relative to body size in the hominin lineage was probably favored by an increasingly complex social life. Any features that allowed group members to communicate more effectively with one another would have been valuable in cooperative hunting and gathering as well as for improving one’s status in the complex social interactions that must have characterized early human societies, just as they do ours today.

Several Homo species coexisted during the mid-

One species, Homo neanderthalensis, was widespread in Europe and Asia between about 500,000 and 28,000 years ago. Neanderthals were short, stocky, and powerfully built. Their massive skull housed a brain somewhat larger than our own. They manufactured a variety of tools and hunted large mammals, which they probably ambushed and subdued in close combat. A closely related lineage, the Denisovans, is known from less complete fossils, primarily from from Asian caves.

Recently, biologists have been able to extract DNA from the bones of Neanderthals and Denisovans, and have compared the genomes of these species to those of modern humans. Early modern humans (H. sapiens) expanded out of Africa between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago. Then, about 35,000 years ago, H. sapiens moved into the range of H. neanderthalensis in Europe and western Asia, and into the range of the Denisovans in eastern Asia. Neanderthals abruptly disappeared about 28,000 years ago. Many anthropologists believe that Neanderthals and Denisovans were exterminated by those early modern humans. But comparisons of Neanderthal, Denisovan, and modern human genomes indicate that there was some limited interbreeding among these species while they occupied the same range. In humans with Eurasian ancestry, 1–

Early modern humans made and used a variety of sophisticated tools. They created the remarkable paintings of large mammals, many of them showing scenes of hunting, found in European caves. The animals they depicted were characteristic of the cold steppes and grasslands that occupied much of Europe during periods of glacial expansion. Early modern humans also spread across Asia, reaching North America perhaps as early as 20,000 years ago, although the date of their arrival in the Americas is still uncertain. Within a few thousand years, they had spread southward through North America to the southern tip of South America.